PIERRE, S.D. – Tax increment financing districts have become a popular approach to supporting the growth of communities in South Dakota. A TIF is a tool that local and county governments can use to pay for improvement projects. As they become more popular, so does the controversy surrounding them.

Supporters argue the districts allow for the development of housing, infrastructure and economically beneficial projects that wouldn’t otherwise happen. But critics say they increase property tax burdens of landowners, lack transparency and oversight, and haven’t been audited to prove they produce net benefits for a community.

This debate recently came to a head in Rapid City after the city council approved a TIF to support a $125 million theme park complex, which a group of residents has forced to a vote so the community can decide if the project is a good idea.

Clash over Libertyland

In August, the council voted in favor of a $27 million TIF that will finance improvements — including infrastructure and demolition of existing structures — to a commercial district in hopes of attracting a Chick-fil-A, Panda Express and other restaurants and businesses to the area.

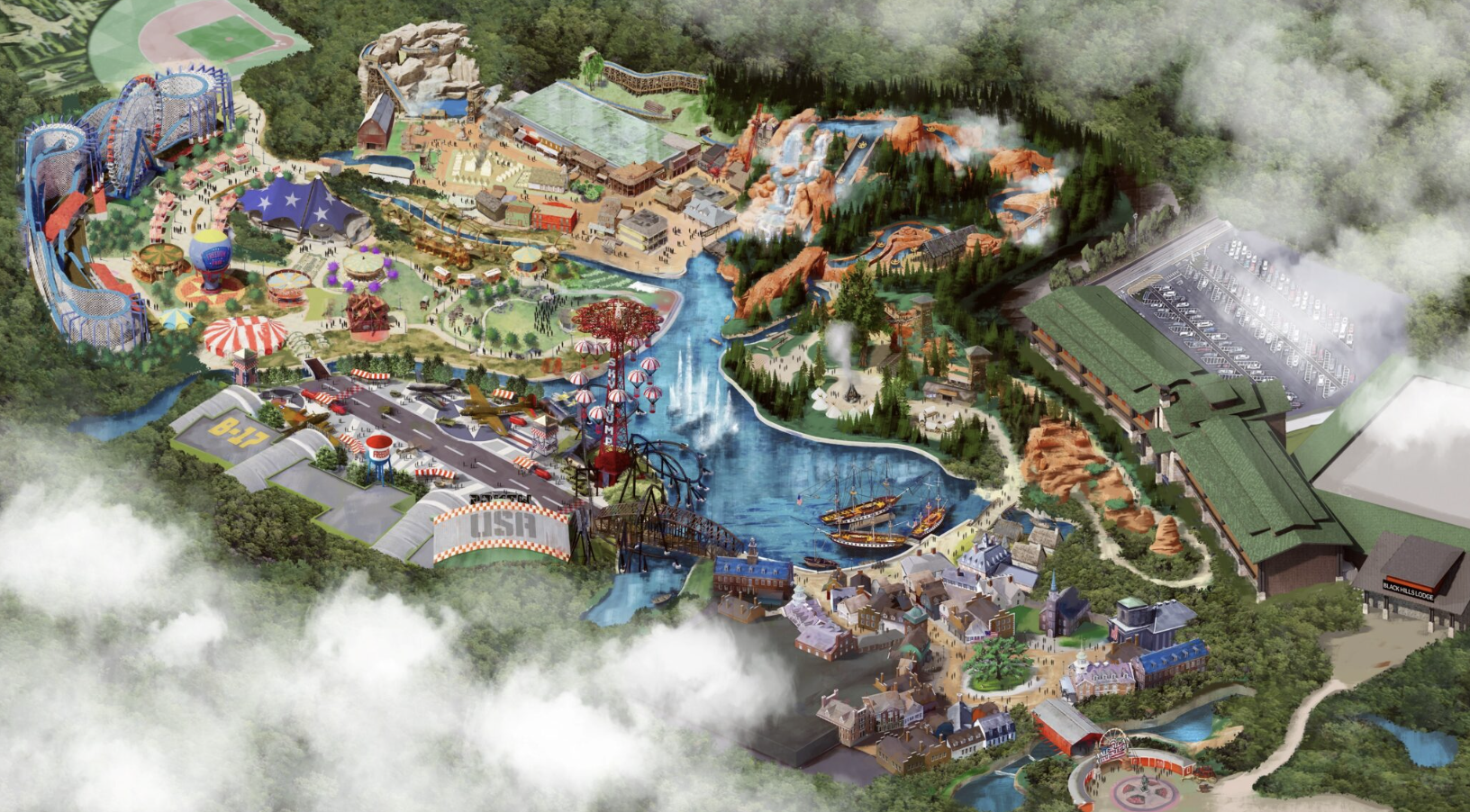

A month later, the council approved another TIF for a $125 million theme park, called Libertyland USA, which will include a hotel, conference center, housing developments and more. Concerned about whether the impacts of the TIF would be good for Rapid City, a group of residents gathered enough signatures to put it to a vote.

The council had previously approved both the Libertyland USA TIF and another TIF for the catalyst district, which includes a sports complex. However, the public notices had referenced the wrong TIFs, so the approval process had to be restarted.

“When you're voting on something, especially an expenditure like that, something that large, you would expect that they would do their homework,” Tonchi Weaver with South Dakota Citizens for Liberty told News Watch.

Grants to private developers

After the TIFs passed, some residents organized a successful petition drive to put the Libertyland TIF to a vote. Weaver was one the organizers of that effort. Among her concerns about the Libertyland TIF is the $46.5 million in discretionary funds included in the project costs.

Weaver said that the funding functions as a grant to a private developer and there’s a wide degree of latitude for what the money can be used toward, which raises questions about whether these costs can be considered to have a public benefit.

“It can be just about anything,” Weaver told News Watch.

Daniel Ainslie, Rapid City finance director, said this funding will pay utilities, hardscape — paths, walls and fences — and landscaping. He said these costs, which make up about 37% of the total costs, are a substantial part of the project.

Without the grant, these aspects would be public infrastructure, meaning the city would have to maintain it. This would mean, for example, when water mains break in 30 years, the city would have to repair it.

“We didn't want city crews to have to go through the middle of an entertainment district and dig up the water lines,” Ainslie said.

Will you support South Dakota News Watch?

SDNW is an independent, 501(c)(3) nonprofit that tells investigative stories, verifies claims and engages with communities to identify solutions. With your gift, we can do even more important stories like this one.

Sen. Taffy Howard, R-Rapid City, said that the use of discretionary funds in TIFs demonstrates one of the ways they have expanded past their original purpose.

The original 1978 state law authorized TIFs as a means to address blighted areas and encourage their redevelopment. Besides creating new classifications and allowing for discretionary funds to be included in the project costs, which the state authorized in 2011, the blight requirement was loosened.

“When you start finding 'blighted' as simply a grass field or when you start adding in the discretionary funds … I really have issues with that. I think that's an abuse of what TIFs were intended for,” Howard told News Watch.

But for the TIF

Supporters of the Rapid City TIF and TIFs in general argue that the improvements that come from the districts have extensive benefits. But for the TIFs, these developments would never happen.

In the 1990s, Doyle Estes, a Rapid City lawyer and real estate developer, helped create the first TIF district in Pennington County.

The TIF paid for a project that stopped flooding on a racetrack. He said he paid approximately $1.5 million for the improvements, and at the time it was created, the district valuation was $3 million.

“When you start finding 'blighted' as simply a grass field or when you start adding in the discretionary funds … I really have issues with that. I think that's an abuse of what TIFs were intended for."

State Sen. Taffy Howard, R-Rapid City

Today, the property values in the district are more than $90 million. Since the district was dissolved a decade ago, all the tax revenues in that district are now funding schools, emergency responders and other government services.

“The county gets more tax revenues in one year than the whole darn taxes cost them and the developer, which was me,” Estes said.

In Pierre, the Clubhouse Hotel and Suites, which includes a conference center and restaurant, was another project created by a TIF.

Sen. Jim Mehlhaff, R-Pierre, said TIFs can be a valuable tool for such projects. He was on the Pierre City Commission when it was approved. Prior to becoming the Clubhouse, it was a Kum and Go truck stop.

"It was pretty much just a big gravel parking lot that trucks would park on," Mehlhaff said.

Without the TIF, it would still be a parking lot, he said.

Benefits beyond the district

Ainslie said Libertyland is likewise dependent on the TIF district.

“The only way that financially it makes sense for them is to have some additional assistance through the TIF to help offset the very substantial construction costs that would go into opening up in Rapid City,” he said.

The project will also have benefits that go beyond the Libertyland developers, Ainslie said.

“The project is bringing what would end up being the largest entertainment destination area in at least a 300-mile radius, and the largest in the state,” he said of Libertyland.

The Libertyland project has indoor attractions, which will help ensure more tourism dollars during the Black Hills area’s “shoulder season.” These are the months outside the peak summer and winter travel times. This will help hotels, restaurants, gas stations and retail shops during the months they struggle the most.

“So it's a good way to try to uplift the overall economy throughout the entire year,” Ainslie said.

Studies of similar facilities have shown that the projects have economic benefits to businesses outside the TIF district. On average, $2 to $4 is spent outside that destination district for every $1 spent inside it, Ainslie said.

Howard pointed out that downtown Rapid City was built without TIFs.

“Throughout history, we did really well as a nation, as a state, as a city without TIFs,” she said.

Impact to taxes

A point of contention for TIF opponents is the increased burden to state taxpayers. Some TIFs require county auditors to impose special levies so that school districts don't lose out on any funding as a result of a TIF.

The influx of tourism that results from the economic TIFs in Rapid City increases sales tax revenue. This is the one tax revenue South Dakota can increase and makes South Dakota less dependent on property taxes to fund government, Ainslie said.

“The only way for the government to truly reduce property taxes is to either significantly reduce government expenditures, which not many people are asking for roads to not be maintained and for public safety to be reduced — or anything like that. So either you reduce government spending or you increase revenue,” Ainslie said.

TIF critics also question whether anyone really knows if TIFs have a net benefit to the communities. Rep. Julie Auch, R-Yankton, said that TIFs need more accountability to be sure they are delivering benefits for the impacts they have to property taxes.

“There's no transparency. There's no checks and balances on these TIFs. There's no governing body that is actually doing an audit annually or biannually on these TIFs,” Auch said.

Estes disputes that the process lacks transparency. The bodies creating the districts have to go through multiple public hearings, and all the project documents are made public, he said.

Risks and rewards

For Weaver, the issue isn’t whether Libertyland is a good project.

“I have tried not to criticize the project itself. If the developer wants to put up — whatever he wants to put up — he's free to do that on his own property. But where we object is to having the taxpayers shoulder part of that burden. And it’s a risk,” Weaver said.

Ainslie said there is no risk to Rapid City taxpayers.

“It's not a gambling of city resources. The city's not investing in this project. The only part of the TIF that the city would be a part of are some actual public roads as well as public utility lines that would be in streets that the city would be constructing — about $8 million worth. And the city would be repaid through the increment,” he said.

The Rapid City Council Monday selected Jan. 20 for the date of the special election, when the voters of Rapid City will decide if they believe the Libertyland TIF will be of benefit to the community.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact statehouse investigative reporter Kevin Killough at kevin.killough@sdnewswatch.org.