Editor's note: This article was updated to add the response from the City of Mitchell. A clarification was also added on Monday, Oct. 6, 2025, at 2:09 p.m. CT concerning water infrastructure to the Box Elder hotels.

PIERRE, S.D. – As more South Dakota counties and cities use a somewhat hard-to-understand method called a tax increment financing district, or TIF, to pay for public projects, scrutiny of them has increased.

There were 264 active TIFs in the state at the end of 2024, an increase of 65 from just four years before. Typical uses include affordable housing and infrastructure for economic development.

Some state lawmakers and residents are concerned about their increased use, but proponents say that in a low-tax state, TIFs are a much-needed option.

“They're one of the few tools in the toolbox for the developer to get projects built in South Dakota,” said Doyle Estes, a Rapid City lawyer and real estate developer.

TIF history and types

Over the past several months, a panel of lawmakers on the state's property tax task force have been listening to public comments and hearing presentations from state officials on TIFs.

At a meeting in September, Rep. Julie Auch, R-Yankton, asked rhetorically how many in the audience could fully explain what TIFs are and how they work.

If most people can’t understand their implications, how can the governmental bodies creating the districts fully understand them, she asked.

“We have city commissioners and county commissioners making decisions in reference to tax incremental financing, and they don't fully understand the concept. And they're putting the burden on the South Dakota taxpayer,” Auch told News Watch.

The law authorizing municipalities to create TIFs was passed in 1978 as a means to help municipalities address blighted areas. Since then, it’s gone beyond that original purpose to allow counties to set up TIFs and to allow classifications of TIFs that help finance other types of projects other than local infrastructure supporting residential areas.

Here are the four classifications of TIFs and the percent of each in the state, based on the increased property values in 2024 from when the TIFs were created:

- Economic development (82%): A district where one or more businesses engaged in any activity defined as commercial or industrial. An example would be water infrastructure servicing a commercial area.

- Local (10%): Used for public infrastructure that benefits the local government, such as infrastructure improvements for housing that doesn’t meet the requirements for affordable housing.

- Industrial (5%): A district for factories, processing of raw materials or wholesale activities. Examples could be a meat processing plant or ethanol production facility.

- Affordable housing (3%): This could be used for infrastructure improvements to support housing development or workforce housing.

How TIFs work

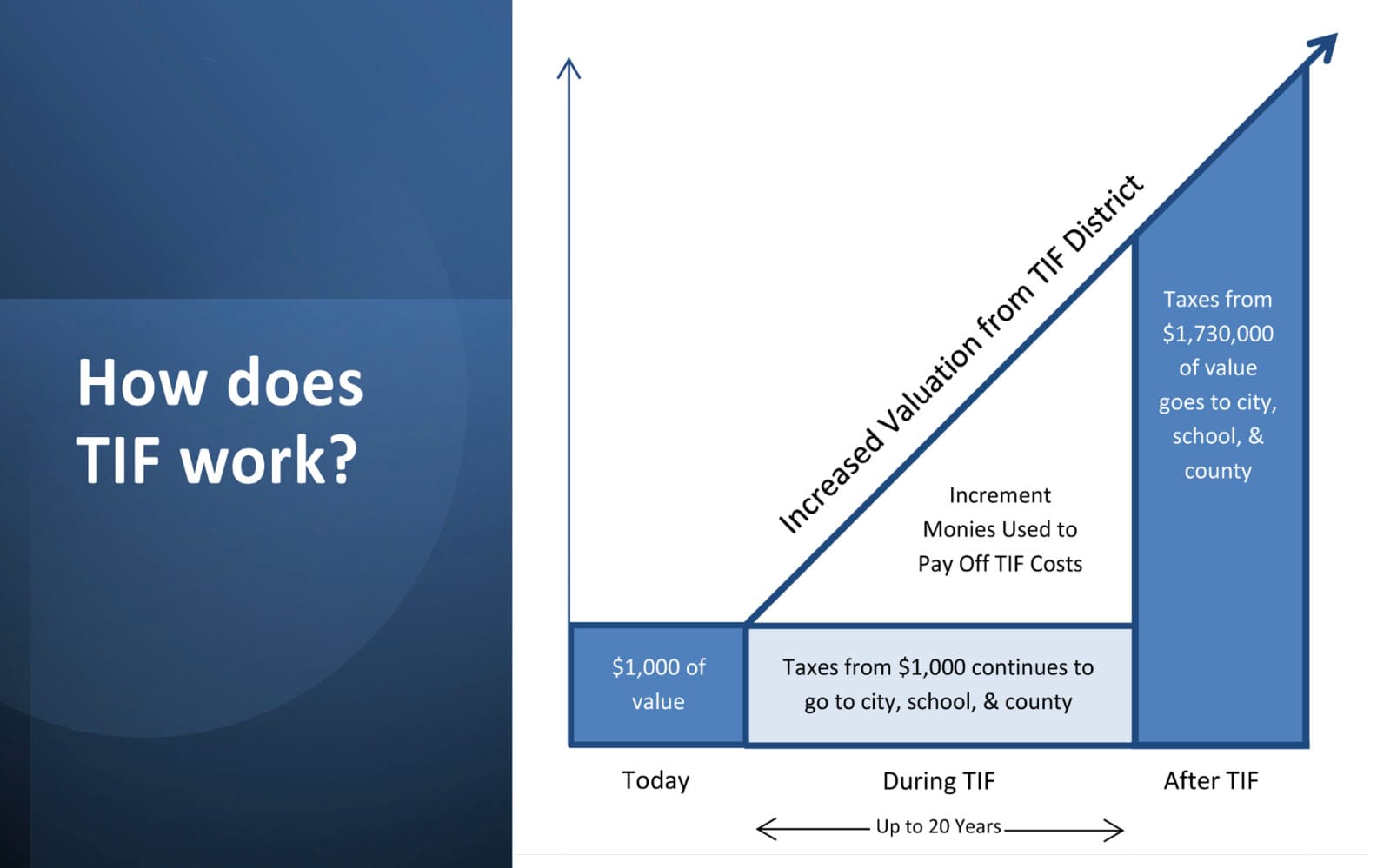

When a TIF district is established, taxes based on the property valuation in the district continue to go to cities, schools and counties as normal. The projects that the TIF pays for increases the property values in the district. Any taxes resulting from that increased valuation over the life of the TIF, which is a maximum of 20 years, go to pay for the project.

While the steps are complex, the basic process goes like this:

- The city or county interested in funding a project defines a geographical area where the improvements will be made. This is the TIF district.

- The planning commission of the county or city creating the TIF holds public hearings on the necessity of the district. If the commission decides it’s needed, then it recommends to the county or city commission that the TIF be created.

- Once the recommendations of the planning commission are accepted, the city or county must adopt a resolution creating the TIF, which officially defines its name, legal boundary and project plan. The project plan explains how the project will be financed, which can be done with special bonds or private financing. The project can be publicly or privately owned, but the costs of the project to be financed are required to have a public benefit. A small fraction of TIFs go to voters to decide.

- The South Dakota Department of Revenue then certifies the assessed value of all property within the district when it’s created. The taxes from this base value continue to go to the city, school and county during the life of the TIF.

- After these costs are repaid — or the TIF reaches the 20-year limit — the TIF is dissolved. At that point, the full property tax revenue within the district, including the increment value, goes to the county to fund schools, public safety, infrastructure and government services.

A tale of two projects

Steve Sibson, a retired accountant and resident of Mitchell, raised concerns about a TIF that town leaders created in May. The city partnered with a developer to pay for the construction of 70 two- and three-bedroom apartments, including garage units, a fitness center and coffee shop.

Sibson told News Watch the city didn’t follow state requirements in creating the district.

Join other South Dakotans and support statewide storytelling.

In addition to the housing development, the project included the construction of a road servicing the complex. Sibson grew concerned because it appears to contain two projects — one that funds the developer for the housing project and another that funds the city for the construction of the road.

Sibson argued these different projects would create different classification of TIFs — an affordable housing TIF and a local TIF. If it's a local TIF, the county auditor is required to impose an additional school levy on property within the school district.

Questioning TIF oversight

Sibson argued at a May 5 city council meeting that state law required Mitchell to get a preliminary classification determination from the South Dakota Department of Revenue prior to approving the TIF. Both the city attorney and developer’s attorney said the state no longer required the preliminary determination.

However, the state does require this step.

Kenda Baucom, marketing and communication specialist with the DOR, said the City of Mitchell requested a preliminary classification determination from the DOR, and a response was provided in April.

Stephanie Ellwein, city administrator for the City of Mitchell, said Monday there was some miscommunication between the city and the DOR about whether the classification was needed prior to council approval.

While the DOR provided the determination in April, the project was classified as economic development. The project plan, however, states that, "Should the State of South Dakota not classify the TIF as affordable housing, the TIF will not be finalized and will cease to exist."

Ellwein said she wasn't sure why the TIF was approved despite the preliminary determination being economic development.

“That told me they were not providing the oversight on these tips, that they were just rubber stamping them." - Steve Sibson, resident of Mitchell

Sibson said that he had contacted the DOR to find out if Mitchell was required to get the preliminary determination and what could be done if the city had not. He said he was told that Mitchell has a lot of TIFs, and he could pursue a referendum to put the TIF to a vote.

“That told me they were not providing the oversight on these TIFs, that they were just rubber stamping them,” Sibson said.

Opponent: TIFs can be 'subsidies for ... private entities'

Sibson said that when TIFs are done correctly, they can benefit a community and result in new growth.

“If they're not done correctly, they end up being simply subsidies for certain private entities. That's my overall concern,” Sibson said.

Estes, the developer who helped pioneer their use, said the TIFs he’s been involved in have brought enormous growth to Rapid City and the nearby town of Box Elder.

One TIF district in Box Elder brought water services to a hotel in Box Elder. As a result of that water infrastructure, four more hotels were later built in Box Elder that wouldn’t have otherwise been feasible projects, he said.

Estes said he built a road in Rapid City that was funded with a TIF, and due to the success of the project, the city is building a fire department, law enforcement center, and a city park.

“Anybody that sees things beyond the end of their nose can see that tax increment districts work,” Estes said.

Part 2: Opponents of tax increment financing raise issues with TIFs, including the increased tax burdens, a lack of transparency, and the lack of auditing to objectively measure their benefits. Supporters say their growth is the product of how successful they have been for the cities and counties that use them. In the next part in this series, News Watch digs deeper into the debate on TIFs.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact statehouse investigative reporter Kevin Killough at kevin.killough@sdnewswatch.org.