SIOUX FALLS, S.D. – Dakotans for Health, a grassroots organization seeking to put an abortion measure on the 2024 ballot in South Dakota, has reached a settlement with Minnehaha County regarding the circulation of petitions at the county administration building.

As part of the agreement, Minnehaha County will formulate a new public use policy that removes references to a designated area for petition circulators and also removes language requiring circulators to check in with the county auditor before engaging in political activity on the central Sioux Falls campus.

Dakotans for Health agreed to keep petition circulators away from the area directly in front of the administration building's main entrance doors and also away from an area a few feet west of the entrance so they don't interfere with people with disabilities getting in and out of vehicles. The group also agreed not to "commence any new action or lawsuit" regarding the county's policy as long as the prescribed changes are made.

The settlement agreement was signed by Dakotans for Health executive director Rick Weiland and Minnehaha County Commission chairperson Jean Bender.

"We're pleased that our First Amendment right to circulate these petitions, which was threatened with this policy, is no longer being threatened," Weiland told News Watch. "We lost some ground in having to go through this process, but we protected our right to be able to circulate at one of the busiest public buildings in the state."

U.S. District Judge Roberto Lange granted a preliminary injunction in June that prevented Minnehaha County from enforcing designated areas and check-ins for petition circulators as part of what opponents called an overly restrictive policy at the county’s administration building.

The policy, recommended by county Auditor Leah Anderson and passed May 2 by the Minnehaha County Commission, came in response to what some county employees and customers characterized as increasingly aggressive behavior from circulators and counter-protestors as signatures are sought for a proposed ballot amendment to enshrine the right to abortion in the South Dakota Constitution.

The rules restricted petition circulation to two designated rectangular areas: one about 50 feet from the main entrance to the building in the parking lot off Minnesota Avenue and the other southeast of the main entrance to the courthouse.

The policy mandated that circulators check in at Anderson’s office prior to conducting political activity “to permit the placement of safety markers and to verify space availability within the designated areas.”

In his June 13 ruling, Lange wrote that Dakotans for Health representatives “have shown a likely violation of their First Amendment rights, and the public interest is served by protecting these rights.” He added that his ruling restrains the county from enforcing any part of the policy that requires “check-in” with Anderson’s office or restricts petition circulators to “designated areas.”

The ruling does not prevent the county from enforcing its previous policy’s rules regarding the behavior of petition circulators, Lange wrote, noting that the county already had provisions in place requiring signature gatherers to conduct themselves in a “polite, courteous and professional manner” and not “obstruct individuals as they enter and exit the building.”

Two-thirds of the way to signature goal

The legal tussle over the county’s petition policy was viewed as crucial to the battle over South Dakota’s abortion ban and whether voters should decide the issue in 2024.

If passed, the abortion measure would add the right to abortion in the South Dakota Constitution and supersede a 2005 state trigger law that took effect when Roe vs. Wade was overturned and made it a Class 6 felony to perform an abortion except to save the life of the mother.

Dakotans for Health needs to collect a minimum of 35,017 signatures to place the abortion constitutional amendment on the ballot. The goal is to submit 60,000 or more to ensure that ballot access isn’t foiled by invalidated signatures or other technicalities. The deadline to submit signatures is May 7, 2024.

Weiland told News Watch on Nov. 21 that the group is about two-thirds of the way to its goal of collecting 60,000-plus signatures.

'Like an invisible cage'

Called the “gold standard” of petition circulation by groups soliciting signatures for ballot measures, the county administration building features a steady flow of foot traffic from the parking lot to its main entrance, where circulators are often stationed with clipboards and requests for support of their political cause.

Some of the petition circulators have clashed with volunteers from the anti-abortion Life Defense Fund, whose founders call the proposed amendment “a grave threat to life in our state.” The group aims to thwart petitioners through its “Decline to Sign” campaign.

“All we’re saying is that people should have an unimpeded right to decide whether to sign petitions and then to vote on issues that affect them,” said Leach.

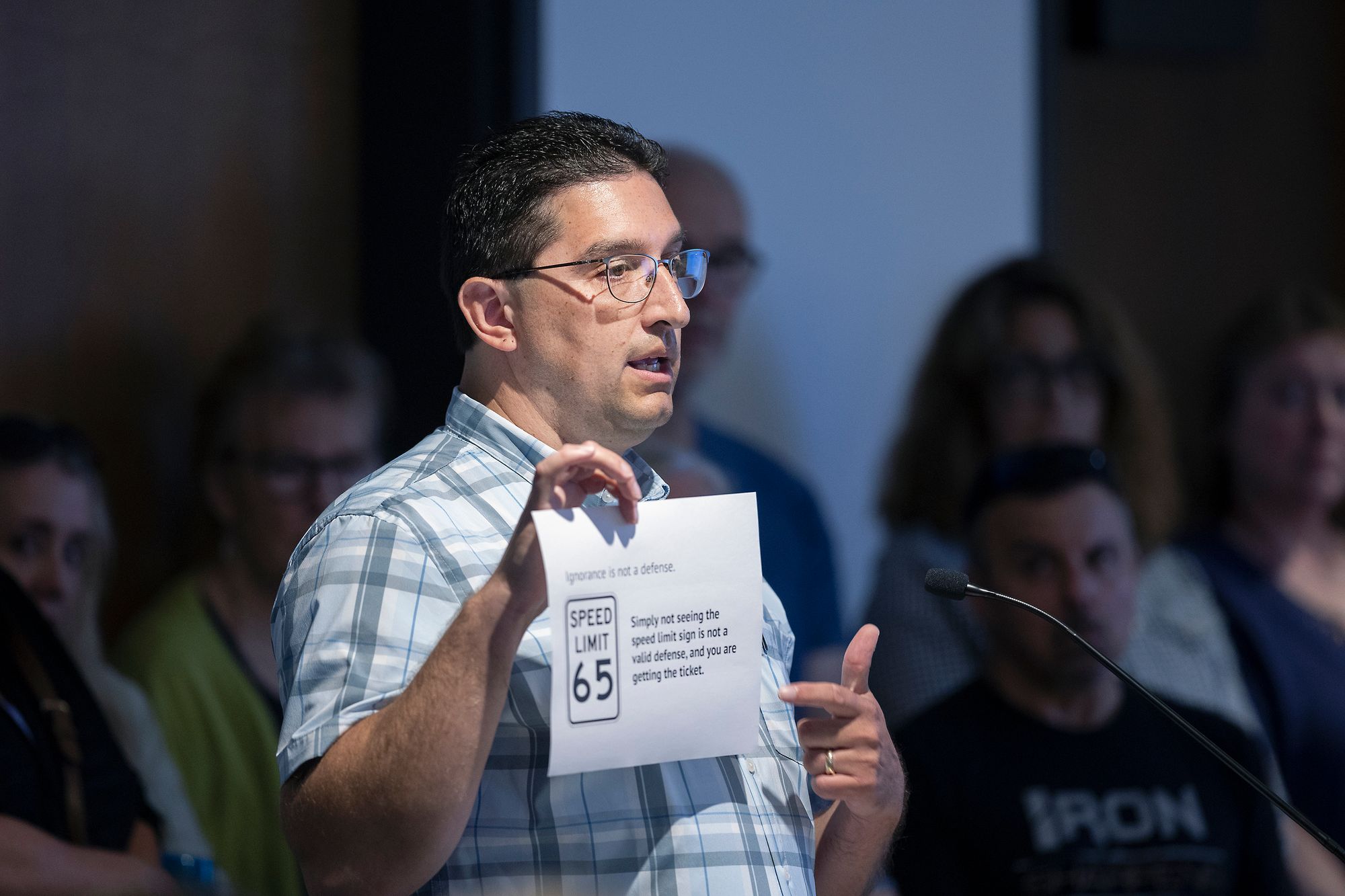

Much of the debate focused on the yellow-striped rectangular box in the parking lot that was a designated area under the disputed policy.

Dakotans for Health claimed it would force circulators to shout at potential signers to go out of their way and potentially walk through parking-lot traffic to engage in conversation.

“It’s like an invisible cage,” said Weiland, whose group is also collecting signatures for an initiated measure on the 2024 ballot to repeal the state grocery tax. “No one’s going to come through there.”

Behind the Ballot: More from South Dakota News Watch

Tax debate: Noem pulls support for grocery tax measure over jeopardized tobacco money

Open primaries: Ballot effort would allow more South Dakotans to choose candidates. But can it pass?

Under the previous policy, circulators were allowed to station themselves on the sidewalk near the entrance to the administration building if they conducted themselves in a “polite, courteous and professional manner” and did not “obstruct individuals as they enter and exit the building.”

Problems started occurring earlier this year, according to the county’s response to the lawsuit, necessitating a policy change “in order to assure that (First Amendment activity) is not overly disruptive and that employees are not subjected to unwelcome, hostile, or harassing speech.”

The scene offered a reminder of why the administration building – serving a county with nearly 200,000 residents, 22% of the state’s population – has been a petition-gathering hub for decades.

People are constantly coming and going from tasks such as renewing license plates, getting a marriage license or registering a deed. Most are county residents with an established address, which means a high percentage of valid signatures, said Adam Weiland, Rick’s son, who oversees petition drives for Dakotans for Health.

The group collected about 10,000 signatures over 12 months at the Minnehaha County building for the Medicaid expansion constitutional amendment that made the 2022 ballot and was approved by voters, Adam Weiland said. He estimated that more than 20% of the group’s overall signature collection comes from the county building, without the duplicate traffic seen at other sites.

“After working Medicaid expansion for 12 straight months, we still hadn’t exhausted it,” he said. “We were still getting fresh signatures down there. It’s just this diverse stream of traffic with a lot of registered voters and a good universe of individuals to be collecting signatures from.”

More from News Watch: Supreme Court ruling won’t stop abortion pill provider near South Dakota

Previous Minnehaha County auditor also proposed changes

Bob Litz, who served as Minnehaha County auditor from 2010 to 2020, said the county’s policy toward signature collectors at the administration building became an issue a few times during his tenure, particularly when contentious issues arose and the deadline for submissions neared.

“I always felt we had to accommodate everybody, and the petitioners don’t have the right to obstruct other people’s access to the building,” said Litz, who is retired and living in Arizona. “Put yourself in people’s shoes. If there was a petition you didn’t care about, would you want to get slowed down going in to take care of business if you’re on your lunch hour and in a hurry?”

He said that the rules proposed by Anderson were “a little more severe than what we had.” But he once floated his own idea for a designated area away from the sidewalk and door to reduce congestion for customers.

The county commission rebuffed the plan, Litz said.

“I proposed that we take a parking space out, yellow stripe it, put a couple of those yellow bollards (posts) at the end of the space, and that would give everybody a lot more room,” he said. “It would be a gathering spot but also a safety buffer for anyone coming in the building. I went in and talked to (the commission) about it, and the proposal was rejected.”

Payday loan ballot measure sparked conflict in 2015-16

Often the commotion comes from conflicting political interests – those collecting signatures for a proposed ballot measure and those trying to disrupt or add information to that process.

When a group called South Dakotans for Responsible Lending pushed for a 2016 ballot initiative to cripple payday lending in the state with a 36% interest-rate cap, citing the industry’s harmful social effects, the campaign faced aggressive opposition from the Atlanta-based owner of North American Title Loans and other industry supporters.

In addition to starting a rival petition to supersede the rate cap and confuse potential signers, Aycox and company hired out-of-state protestors in 2015 to congest petition-gathering areas, such as a downtown Sioux Falls coffeehouse owned by South Dakotans for Responsible Lending co-founder Steve Hildebrand.

Some of the discord spilled over to Rapid City in Pennington County, where operatives promoting the payday loan industry’s petition clashed with South Dakotans for Responsible Lending circulators.

Police were called numerous times to the county administration building in October 2015, weeks before the deadline to get on the 2016 ballot under the previous rules. Complaints also came from customers who said they were accosted by signature-seekers while trying to enter the building.

Pennington County designated areas for petition activity in 2015

Holli Hennies, office manager for the Pennington County Commission, told News Watch that the policy was changed after those episodes to create designated areas for gathering signatures in Rapid City.

Those areas were on the south sidewalk near the main entrance doors for the courthouse and the south sidewalk below the second-floor main entrance doors for the administration building.

The policy, amended in 2018 to include the elevated entrance area outside the second-floor main entrance doors, states that a petition circulator “may engage in discussion, but may not verbally or physically harass, threaten or intimidate anyone for any reason” or “prevent access to the facility or block pedestrian flow to and from the entrance/exit doorways.”

Anderson and other Minnehaha County employees said in court that the Pennington policy was used as a template of sorts to create the new rules for Minnehaha. But Hennies told News Watch that the Pennington County changes didn’t move circulators farther away from the entrance.

“Petition circulators are restricted to the area right in front of our building, so we’ve not moved them away,” she said. “We’ve tried to find the balance of getting people in without being approached if they don’t want but allowing the circulator access to the traffic of our building.”