NEWELL, S.D. – Tariffs, an international trade war and other market conditions are creating great volatility across the South Dakota agricultural industry, with West River ranchers celebrating record prices and some East River soybean and corn farmers facing potential financial disaster.

Farming and ranching are always full of ups and downs and winners and losers. But 2025 is proving to be unusual in the way some agricultural sectors are riding high while others are worrying about potential foreclosures.

President Donald Trump's trade war with China is almost exclusively negative for row crop growers, but his multitude of new tariffs are lifting some sectors, livestock producers in particular.

At a stock sale at the Newell Sheep Yards, replacement ewes were drawing "very high prices" on a recent Thursday in September, according to facility manager Barney Barnes.

But the ebullient mood on display in Newell belies the misery being felt by thousands of farmers and farm families in the eastern half of South Dakota.

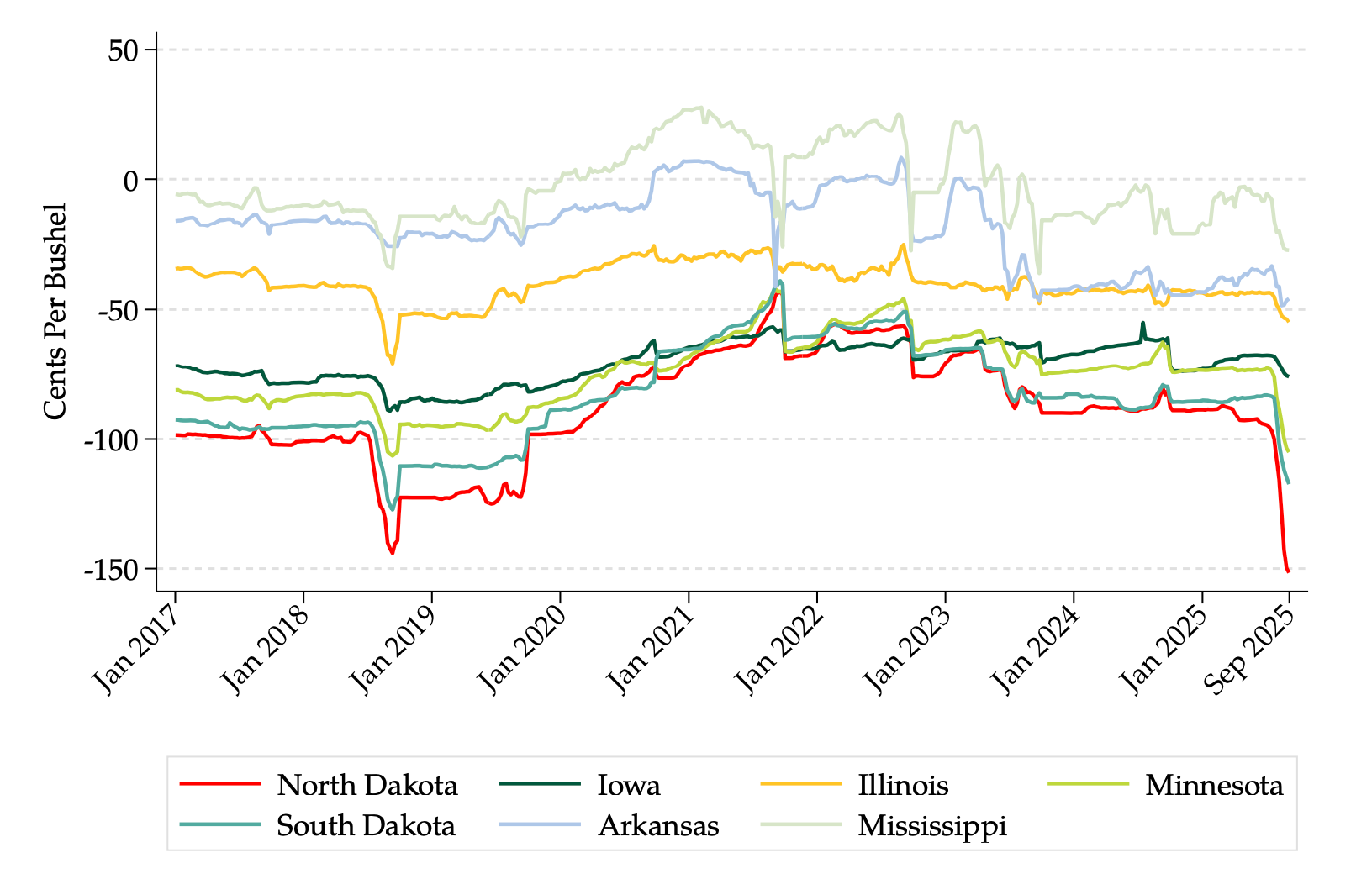

Largely due to the trade war with China, which has led the Asian nation to forgo orders for American soybeans and turn instead to South American producers, row-crop farmers in eastern South Dakota expect low demand and low prices for their products this year.

"When you look at crop markets like corn and soybeans and wheat, they're all just dead," said Scott VanderWal, president of the South Dakota Farm Bureau Federation. "They're all in a loss position."

Republican U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds of South Dakota told News Watch that row-crop farmers in South Dakota have suffered for years without favorable trade deals, adding that Trump's goal is to enact deals that "change the balance of trade."

After meeting with a dozen row-crop farmers, lenders and agricultural leaders in Pierre on Sept. 22, Rounds cautioned them that the struggles of 2025 might continue into 2026 if new trade deals aren't made by then.

"The American producer is the tip of the spear in these trade battles," he said.

Rounds later suggested that perhaps some of the new federal revenue from tariffs could be used to offset losses by American farmers.

Concerns greatest in soybean industry

The worst hit among South Dakota’s roughly 28,000 farms and ranches are the 5,000 producers who grow soybeans.

With no China sales, they are left with the untenable situation of having a huge crop of beans ready for harvest and a gap in the traditional marketplace to sell them.

“If you don’t have a market or a good price for the product, you don’t have a working wage for the families, and there have been bankruptcies already,” said Jerry Schmitz, executive director of the South Dakota Soybean Association. “Especially the young families, when we start losing those, they’re the people who are our future and who should be producing for the next few generations.”

“With less demand, and a bumper crop coming through this year, that will all create downward pressure on prices,” said DaNita Murray, executive director of South Dakota Corn, the grower’s association. “Things are tightening up, and the mood out there ranges from worried to grim.”

In a typical year, soybean producers generate about $5 billion for the state economy, Schmitz said. About 30% of the 230 million bushels of soybeans grown annually in South Dakota are exported to China, he said.

As the annual soybean harvest begins, producers may have to pay to store their beans in grain bins or elevators, but some may have to bag them or store them on the ground, Schmitz said.

“In these trade deals with China, we’re making agreements that make things more fair for workers in Detroit or Chicago, but that’s being done at the expense of small family farms that are producing soybeans,” he said.

Schmitz said he and other agricultural leaders are seeking new markets for soybeans and related products, including for oils that can be used in biofuels, such as diesel.

Some hope arrived with a recent trade delegation from Nepal, Sri Lanka and other countries that visited South Dakota, though those nations are much smaller soybean consumers than China. Establishing markets in new countries is a slow process that can take years, Schmitz said.

Meanwhile, China is likely to increase soybean purchases from South America, as it has during previous trade wars. Once those new markets are established, they cut into the market for American soybeans on a permanent basis, Schmitz said.

Corn growers see low prices amid bumper crop

South Dakota’s corn farmers, many of whom also grow soybeans, are also having a tough year.

Even as they could set a record of more than a billion bushels grown in 2025, up from about 850 million last year, they are plagued by low demand and low prices that could stifle profits, said DaNita Murray, executive director of South Dakota Corn, the grower’s association.

Similar to the soybean industry, corn farmers are seeing no orders from China as well as slowed interest from the two major importers of American corn — Canada and Mexico, Murray said.

“With less demand, and a bumper crop coming through this year, that will all create downward pressure on prices,” she said. “Things are tightening up, and the mood out there ranges from worried to grim.”

A lack of details about trade deals made by Trump, including with the United Kingdom, have caused uncertainty in the markets that has further stagnated prices, Murray said.

About half of South Dakota corn is used for ethanol and the remainder is used for animal feed and exports, she said. Corn was selling for about $3.60 a bushel in early September.

Support stories about rural South Dakota with a tax-deductible donation.

Potential negative outcomes include farmers having to pay to store their grain and, in the longer term, an inability to afford equipment or fertilizers that are subject to import tariffs in the upcoming planting season. Those impacts could spill further down the line in the agricultural economy in the state, Murray said.

VanderWal said if the cost of "inputs," that include seed, fertilizers and land rents or mortgage payments continue to rise, and prices don't rise along with them, some South Dakota farmers might not be able to survive.

"So here we go again, with higher input costs and a low price for our output that is below break even," he said. "People who don't have a lot of capital built up or pretty solid equity are going to have a problem."

Beef, lamb producers having a very good year

With a strong national market for lamb meat in 2025, sheep producers from across northwestern South Dakota were seeing strong prices and solid profits as they sold their ewe and feeder lambs to dozens of buyers in the auction ring in Newell in September.

The positive outcomes for the state's relatively small sheep production industry is being felt on an even greater scale by South Dakota's far larger cattle ranching sector, which is anchored west of the Missouri River and is seeing record prices for cows and calves in 2025.

Nationally, beef producers have benefited from a reduction in supply as ranchers slowed production after the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to the lowest overall inventory since the early 1960s.

Ranchers in the cow-calf industry have benefited from price increases caused by tariffs placed on beef imports that have reduced the amount of foreign-grown meat coming into the U.S., including from Mexico due to concern over a New World screwworm outbreak.

Jack Orwick, who has about 2,000 sheep and 350 head of cattle on his ranch in Butte County about 40 miles north of Newell, said he expects a great year for revenues in 2025.

Orwick said he recently sold open heifers for $3,100 a head, the highest price ever.

“That’s just nuts, record high prices, and nobody’s ever seen anything like it,” he said. “The lamb market is pretty strong, too, and it’s expected to get stronger in the fall.”

Demand for beef among American consumers has remained high, and their willingness to pay higher prices for ground beef and steaks has not waned despite consistent inflation, Orwick said.

Other South Dakota markets holding stable

Other markets in South Dakota are holding strong, including the pork, turkey and dairy industries.

"Pork producers are currently experiencing market levels that are allowing them to be profitable," Abbey Riemenschneider, spokeswoman for the South Dakota Pork Producer Council, told News Watch in an email. "Like many other industries, we are concerned about existing and potential tariffs that could be put in place, as approximately 25% of U.S. production is exported."

VanderWal said the state’s dairy operators are also having a good year. South Dakota has seen a recent surge in capacity to turn milk into cheese, and the demand for milk and cheese has remained high across the country this year, he said.

Turkey production, largely led by Hutterite colonies, also remains stable, VanderWal said, though bird losses are reaching the hundreds of thousands due to avian flu this fall.

For South Dakota producers who lose money due to tariffs and trade conflicts, it's possible Congress might approve cash bailout payments, as it did in South Dakota with the Market Facilitation Program during the Trump trade war in 2018-2020.

"That's not the way farmers want to make their money, but if it'll keep people alive financially for another year, it might be necessary," VanderWal said.

VanderWal, who also serves as vice president of the American Farm Bureau, said he remains optimistic that short-term pain will result in long-term stability in American agricultural markets.

But help might not come soon enough for farmers without sufficient capital or equity, he said.

"We're talking about profitability to the administration and policymakers and helping them understand that the ag economy is not good, and that we're going to start losing people if things don't change around," VanderWal said.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact Bart Pfankuch at bart.pfankuch@sdnewswatch.org.