Medical experts in South Dakota and across the country are concerned that reluctance among some people to get vaccinated against COVID-19 may prolong the pandemic, delay a return to normal life and possibly lead to more deaths.

Health officials say that the U.S. and individual states are in a race to reach “herd immunity,” a level at which enough people are immune to the coronavirus to curtail its spread and reduce hospitalizations and deaths from the virus.

South Dakota has been a national leader in providing coronavirus vaccines to older residents and others at high risk of complications from COVID-19.

But as the vaccine rollout expanded to Phase 2, making anyone 16 and older eligible for vaccination, the demand for shots has waned and concerns have risen that herd immunity may be unobtainable.

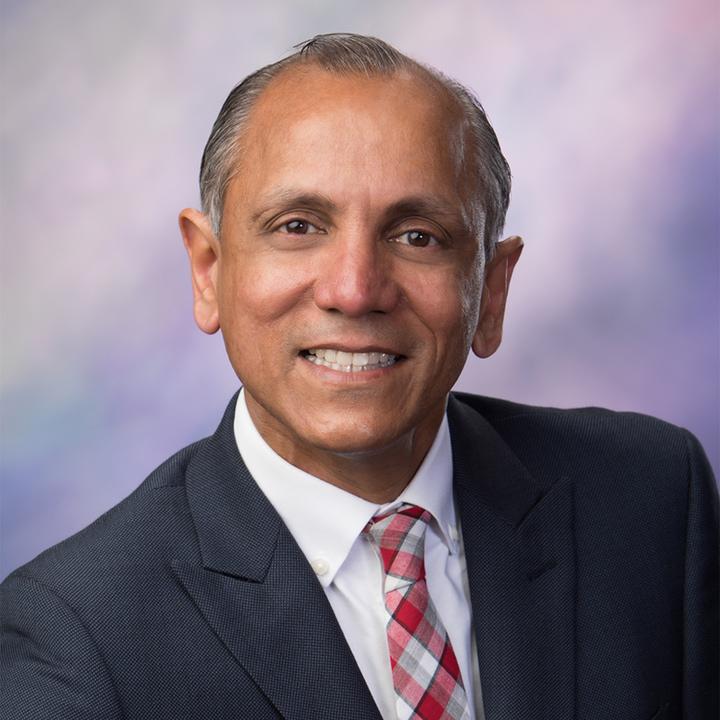

“It’s definitely concerning, and it’s truly a race against time,” said Dr. Shankar Kurra, vice president of medical affairs at Monument Health in Rapid City. “If we don’t get to that threshold of herd immunity, we could end up losing the race and having a new surge or wave of cases and unfortunately more hospitalizations and deaths.”

National surveys and reports from medical experts in South Dakota reveal that vaccine hesitancy is more common among young people, rural and low-income residents, those with lower education levels and among some religious and political groups. Misinformation about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines is seen as a common reason people are deciding not to get vaccinated.

Failure to get enough people vaccinated could allow the current COVID-19 pandemic to linger and raises the likelihood that coronavirus variants, which appear to spread faster and more easily, would take hold and spread freely even among those who were vaccinated against the original version of the virus, Kurra said.

“That is what the race is about, to stop this pandemic, to prevent transmission so we don’t get new variants, and finally to return to normal,” Kurra said. “We can do this and actually end everything, and we won’t have to be talking about COVID anymore.”

South Dakota medical experts will be watching closely over the next month or so to see if vaccination rates remain stable now that eligibility has expanded to the largest population group so far.

“It’s very important that we go through this Phase 2 with good numbers showing up to get immunized,” Kurra said. “If we fail to do that in these hesitant groups, they will serve as a reservoir for the virus so it can continue to spread and possibly lead to more variants.”

Teacher remains on vaccine fence

Meagan Jensen, 25, is an agriculture teacher at Sturgis High School who has followed the progress of the vaccination effort in the news and has so far decided not to get vaccinated.

Jensen, a graduate of South Dakota State University who now lives in Rapid City, said she is well aware of the risks of serious illness from COVID-19 and has gone “back and forth” on whether to get vaccinated.

Jensen said she has friends her age who contracted COVID-19 and had “extreme” symptoms that included hair loss and the inability to taste or smell. Jensen said she wonders if she will need proof of vaccination to travel abroad to destinations such as New Zealand. She also worries that failing to get vaccinated could put her students at risk.

In school buildings, Jensen said, she tries to maintain social distance from students and colleagues, and wore a mask when it was mandatory. Jensen said she has not worn a mask in the classroom since safety restrictions eased in the Meade County School District and masks were recommended but not required.

Jensen said she has concerns that any vaccine, including the COVID-19 vaccine, could reduce fertility in women, either in the short or long term.

Jensen said she was raised to think for herself and to respect the right of individuals to make their own decisions. She said she is aware that she now qualifies to receive the vaccine and feels that health providers have done a good job of making it easy to sign up for shots, but she remains reluctant.

Mostly, Jensen said she feels as if the vaccine probably is not necessary for her because she has gone this long through the pandemic without contracting COVID-19.

“I’m around FFA [Future Farmers of America] students all the time, so I’ve probably been exposed multiple times and I haven’t gotten it,” Jensen said. “If I haven’t gotten COVID already, maybe I won’t.”

Doctor addresses vaccine ‘myths’

Experts say that herd immunity can be obtained in two ways: either by enough people contracting COVID-19 and building up antibodies as they get sick and recover; or the much safer route of vaccinating enough people against the virus. No one is certain about the percentage of people who must be protected in order to achieve herd immunity, but many experts estimate it takes about 80-85% of the overall population.

Dr. David Basel, vice president for clinical quality at Avera Health in Sioux Falls, said failure to reach herd immunity would make it more likely that coronavirus variants will become the dominant strain of the virus in South Dakota and beyond.

If a large pocket of people in South Dakota or elsewhere does not obtain immunity to the coronavirus, it creates a crucible of sorts for coronavirus variants to take hold and spread, thereby raising the potential that variants could infect those who received immunizations or had COVID-19 before.

“From my standpoint, I feel like we’re in the race of the vaccine versus the variants,” Basel said. “As long as our case rates are continuing to go back up again, I feel a sense of urgency.”

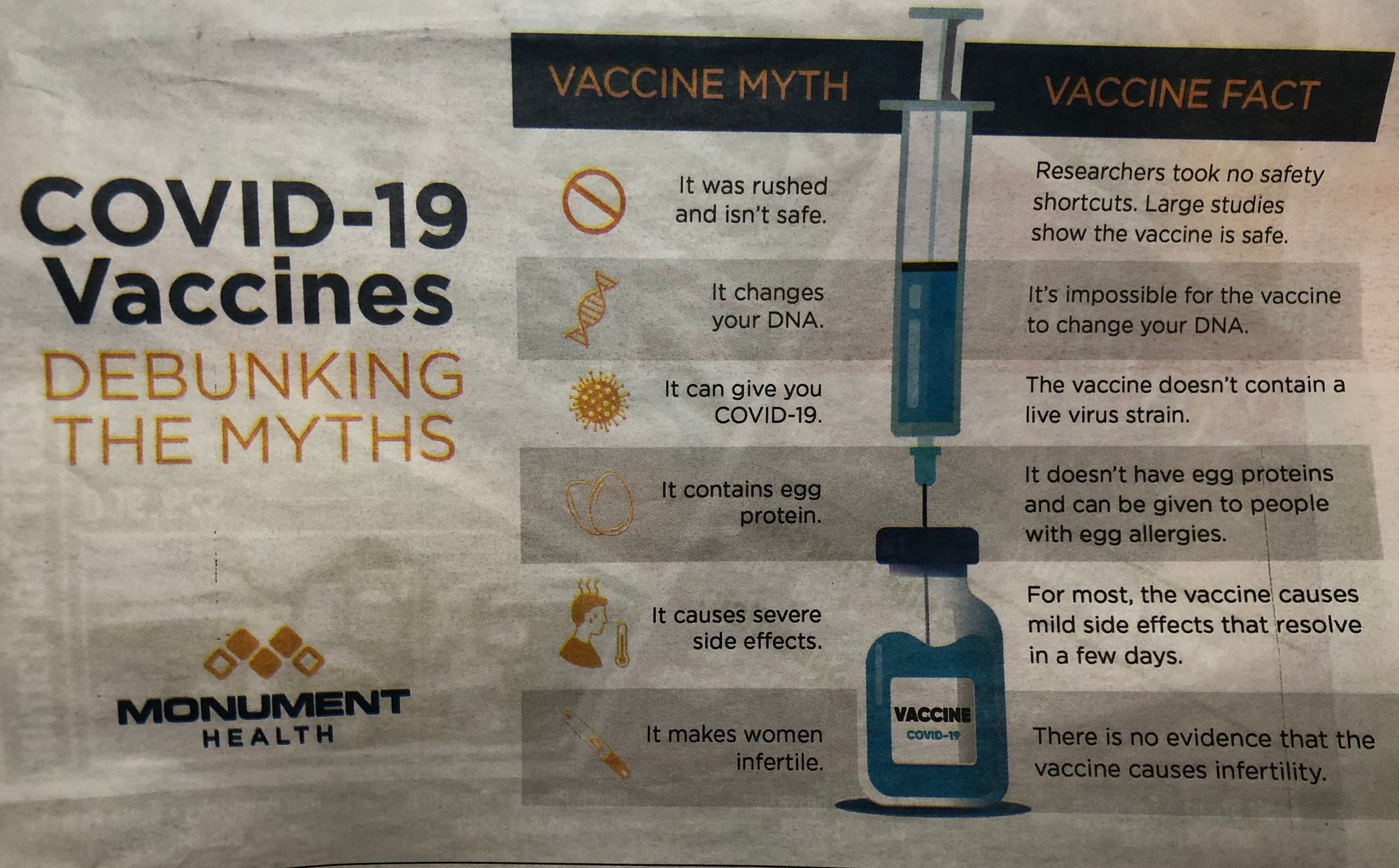

Basel said the medical community is encouraging vaccinations while simultaneously trying to tamp down misinformation that he said overstates the risks of health problems or side effects from the vaccines.

“There’s a whole host of myths that are out there that we try to fight,” he said.

Among the false narratives about the COVID-19 vaccines, he said, are that the vaccines can cause COVID-19, that the shots reduce fertility, that the vaccines were rapidly authorized by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration without proper testing and trials, and that side effects from the shots can be severe.

Basel said there is no evidence the vaccines affect fertility, and says they do not contain a live virus that could infect a recipient with COVID-19. The vaccines were tested using typical protocols even though the process was expedited to get vaccinations started as quickly as possible amid the pandemic that has killed more than 560,000 Americans and almost 3 million people worldwide.

Basel said that at 37 Avera hospitals across four states, the health group has not had a single patient hospitalized due to a COVID-19 vaccination.

Nursing assistant to skip shots

Jessica McDonald, 26, said that all of the residents at the South Dakota nursing home where she works as a certified nursing assistant have gotten vaccinated for COVID-19, but that she is not planning to get a shot.

McDonald, who lives in Piedmont, said she feels that the COVID-19 vaccines were rushed through the authorization process by the FDA, and she is not convinced the vaccinations are completely safe.

“I have this one to worry about, so I can’t take any chances,” she said, pointing to her 4-year-old daughter as they ate lunch in Rapid City. “It was rushed, like an emergency thing.”

McDonald said she heard from some co-workers that they regretted getting vaccinated, but she couldn’t say exactly what they regretted except that they felt pressured into getting the shots by family members.

McDonald said she does not consider herself a staunch vaccination opponent, or “anti-vax” person, but she noted that she does not get the annual immunization shot against influenza. She has had allergic reactions to some past vaccinations. She said she feels like the risk of negative outcomes from the vaccine outweigh the potential risks from contracting COVID-19.

“I think I’ve made up my mind,” she said. “I trust my immune system.”

Basel said the population can be divided into three groups when it comes to vaccines: The “eager beavers” who want vaccines as quickly as possible; the anti-vaccination group that is opposed to any vaccines; and the “fence sitters” who may want more information or need prompting to get vaccinated.

Avera and other health systems in South Dakota are still administering vaccines at a good rate, but some experts are concerned that the interest has waned among groups that recently became eligible for shots, including the large 18-65 age group without underlying medical conditions.

“We’re not being overwhelmed … people aren’t necessarily breaking down our doors and having two or three people waiting for a shot,” Basel said. “We could reach a point where the demand is exceeded by the supply, but we’re not there yet.”

Sanford Health recently announced that it had opened vaccinations up to people who walked into vaccination sites and who did not have an appointment. But the effort to promote vaccinations suffered a setback this week when the CDC temporarily halted use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine due to rare but potentially deadline incidents of blood clots in vaccine recipients.

The undecideds remain the target of campaigns to increase vaccination rates.

Basel said it is critical for those who are hesitant to get vaccinated to make an educated, sensible risk analysis when it comes to the COVID-19 vaccination.

“A lot of people say, ‘I’m worried about a potential long-term risk of vaccinations and I’d rather avoid those if possible,’” Basel said. “But you’re really making a choice between a very low, very theoretical risk of a side effect or adverse effect from the vaccination versus a known, considerably higher, clear and present danger of adverse effects of COVID – because we’re still seeing people get hospitalized, still seeing people of all ages dying and still seeing other long-term impacts like brain fog and other negative outcomes.”

"You’re really making a choice between a very low, very theoretical risk of a side effect or adverse effect from the vaccination versus a known, considerably higher, clear and present danger of adverse effects of COVID." -- Dr. David Basel, Avera Health

‘Not a test bunny’

Randy Dudek of Rapid City said he received the vaccination against COVID-19 but only because he was required to as an electrician who sometimes works at Ellsworth Air Force Base in Box Elder.

“I’m not a test bunny for anybody,” he said.

Dudek, 32, said he also has concerns about whether the vaccine-approval process was rushed. He gets his information about the vaccines from CDC bulletins sent to his work email and from news outlets, but not social media, which he said is rife with misinformation.

Dudek, a married father of two, said his wife has not gotten vaccinated because she works from home.

“I know it [COVID-19] affects everybody differently, but I would consider myself and my wife to be pretty healthy,” he said.

South Dakota had its peak COVID-19 infection and death rates in November and early December; the state so far has had about 105,900 total COVID-19 cases and 1,950 deaths.

The state has been a consistent leader in COVID-19 vaccination rates among U.S. states since the phased-in vaccination process began.

As of April 13, 2021, the state had about 306,650 people who had received one dose of any vaccine, a rate of about 51.0%, and about 217,950 people who were fully vaccinated, a rate of about 36.5%. In the U.S. as a whole on that date, about 122.3 million people had received one dose, a rate of 36.8%, and roughly 75.3 million people were fully vaccinated, a rate of 22.7%.

On the basis of national surveys conducted in September and December, the CDC reported that the percentage of respondents who did not intend to get vaccinated had fallen from 38.1% in September to 32.1% in December.

The surveys showed that several population and socioeconomic groups were more likely to express hesitancy to get vaccinated, including younger adults, women, non-Hispanic Blacks, adults living in rural areas, adults with lower educational attainment and lower incomes, and those without health insurance. All vaccinations in South Dakota are free for patients.

A poll in late March by the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation showed that among all population groups, Republicans and white evangelical Christians were most likely to say they won’t get vaccinated, with almost 30% of both groups responding that they will “definitely not” get shots.

The overall population of people who said they would “definitely not” get vaccinated remained relatively unchanged over the past few months, with 15% in that category in December compared with 13% in March.

The poll had some good news, however, in that fewer respondents reported they were in “wait and see” mode and had moved more favorably toward getting vaccinated. The poll also showed that more Black respondents, who earlier were among the most reluctant to get vaccinated, had received vaccinations or said they planned to soon.

Still, the Kaiser polls have highlighted the challenges the medical community faces in trying to encourage those who are hesitant to change their minds and get vaccinated.

“And while the poll indicated that some arguments are effective at persuading hesitant people — such as sharing that the vaccines are nearly 100% effective at preventing hospitalization and death — those messages do almost nothing to change the minds of people who have decided not to be vaccinated,” the March 30, 2021, Kaiser report stated.

A report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in early April showed estimated vaccine hesitancy rates for the nation, and indicated that hesitancy was greatest in the Great Plains and Southeast regions. In South Dakota, the estimates showed greater hesitancy in the middle third of the state compared with the east and west edges.

In South Dakota, the state’s mostly rural population may face geographic challenges in getting vaccinated easily, said Tim Heath, immunization program manager for the South Dakota Department of Health.

“We’ve got a good population of farmers and ranchers who may not want to stop what they’re doing to go down and get the vaccine, and then do so twice,” Heath said. “For the most part, we try to go where people are and get them vaccinated. We are expanding places where the vaccine is available … and relying on local providers.”

South Dakota has a history of high rates of vaccination against the flu, one measure of the willingness of a state’s population to accept the efficacy of vaccines in general.

According to the federal Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, South Dakota had the fifth-highest rate of flu vaccinations in the nation in 2019-2020, with 58.7% of residents six months or older getting the flu shot (Rhode Island was highest with 60.9%). South Dakota led all Great Plains states in flu vaccinations that year, with Nebraska the next closest (58.3%) and Wyoming the lowest (47.3%).

But state health and medical officials still face significant hurdles in educating and encouraging vaccinations for South Dakotans who have been reluctant to get the COVID shots so far, even as the state has opened eligibility to Phase 2, or anyone over 18.

Heath said the state has done a good job of vaccinating people 65 and up, those at the highest risk of serious complications or death from COVID-19.

Young adults and some middle-aged people, especially men, may not regularly see a doctor who likely would provide them with authoritative encouragement to get vaccinated, Heath said.

“They’re generally young, healthy and may not always go to the doctor for wellness visits even if those are covered by insurance,” he said. “They may not have that constant, once-a-year touch with their providers.”

"We need to get the word out that the vaccine is free, it works, so come in and get it." -- Tim Heath, South Dakota Department of Health

Mother hesitates, but no longer

Amanda Williams, an Iowa native who now lives and works in Rapid City, said she has underlying medical conditions that qualified her for a shot very early in the vaccination phase-in but decided against it because she was “nervous and scared.”

Her parents, ages 59 and 66, had fairly severe side effects after their first dose that included weakness, fatigue, aches and pains. The second doses did not cause side effects, she said.

Williams, 41, said she weighed the risks of exposure to the virus versus her perceived risks of getting vaccinated and chose not to get the shots.

But on a recent day, while at work cleaning tables at the food court at the Rushmore Mall in Rapid City, Williams said she had decided to register to get vaccinated.

She began to worry that working among so many diners who were unmasked could put herself, her parents and perhaps her daughter at risk of getting COVID-19.

“I suppose I should have been more concerned about the virus than the shot because I work around so many people,” Williams said.

The deaths due to COVID-19 in South Dakota so far have been largely in the 60-plus age group, with 78% of the 1,950 deaths taking place in that age group.

In early April, the state reported a 7% rise in COVID-19 cases in the 20-29 age group over a six-week period, making that group responsible for about 19% of all active cases in the state at that time.

Heath said some younger residents may not have had prior exposure to transmittable diseases such as measles and polio that were successfully diminished by vaccines. But he said disease data show that cases of those illnesses tend to rise anytime a reduction in vaccinations occurs.

“We’re getting further away from people seeing these vaccine-preventable diseases in the past and how horrible they are,” Heath said. “But it’s a never-ending cycle. We have a drop in coverage, and then we see a rise in cases in an area.”

Heath said the state is preparing surveys to drill in on who is hesitant to get vaccinated in South Dakota and why. Those results could drive further educational campaigns and target resistant populations better, he said.

“We need to do some more push media-wise out there to reach some of those harder-to-reach populations,” Heath said. “We need to get the word out that the vaccine is free, it works, so come in and get it,” Heath said.