A significant spike in the number of suicides in South Dakota in the first three months of 2021 has put the state on pace for a record year for suicide deaths and has prevention experts worried that a long-range mental-health crisis may be emerging.

New data from the state Department of Health show that from January through March 2021, 59 people died by suicide in South Dakota. By comparison, 28 suicide deaths were reported in the first three months of 2020, and 40 suicide deaths occurred in the first three months of 2019.

If the pace of deaths in early 2021 continues, the state would see a record 236 suicides in 2021, a 27% increase in deaths compared to 2020, when there were 186 suicide deaths, and a 70% jump over 2010, when 139 people died by suicide.

State officials have not yet reported data regarding age, gender, ethnicity and location of the 2021 suicide deaths, but prevention experts are increasingly concerned that young adults and health-care workers may be at higher risk and that school-age children face the greatest risk.

Lingering stress from the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with existing mental-health conditions are seen as possible causes for the rise in suicides in early 2021.

State prevention experts were surprised by the rapid rise in suicides because the rest of the nation saw declining suicide deaths in 2020 and because the number of suicides in South Dakota in 2020 and 2019 went virtually unchanged.

In South Dakota, 186 people died by suicide in 2020, compared with 185 in 2019 and 168 in 2018. Suicide is the the ninth-leading cause of death in South Dakota, but it is the second-leading cause among residents ages 15 to 34, according to the Helpline Center, a statewide suicide prevention agency.

Pennington County, home to Rapid City, has seen a significant number of suicides so far in 2021, with 21 deaths reported in the first six months of the year compared to 34 deaths in all of 2020, according to a local suicide prevention organization.

Meanwhile, requests for help related to suicide are also up so far this year. The Helpline Center has received 1,163 suicide-related calls from across South Dakota in the first six months of this year, compared to 941 calls at this time last year.

More people were admitted to Avera Behavioral Health over the past 12 months than during that same time frame in previous years. Normally, about 6,000 admissions are made each fiscal year. From July 2019 to June 2020, there were about 5,300 admissions. From July 2020 to June 2021, there were more than 6,700 people admitted.

Most of those admitted to the hospital have made a plan or intend to die by suicide, said Thomas Otten, assistant vice president for behavioral health services at Avera Health.

“That’s a pretty good indication that there are more attempts at suicide happening in our region,” he said.

The first quarter 2021 mortality data does not include information from the Indian Health Service, which did not respond to a data request for this story. Historically, however, the suicide rate for Native American residents of South Dakota is estimated to be about 2.5 times higher than the rate for caucasians, according to the department of health.

Suicide prevention specialists say they saw a recent rise in attempts and deaths by suicide among people in their 20s and 30s. In Pennington County alone, 12 of the 34 people who died by suicide last year were in the 20-39 age group, according to the Front Porch Coalition.

While specific age data for the last year was not yet available, advocates say they’ve seen more children with suicidal thoughts over the past year. Multiple new programs aimed at youth suicide prevention and training for youth on how to detect warning signs have started across the state in response.

The Helpline Center recently started mental health training for students in grades 10-12 to learn about suicide warning signs. The Front Porch Coalition and Rapid City Police Department started a program in the fall that works with children who are considered at high risk for suicide or with those who know someone who died by suicide.

“Kids particularly had a difficult time with COVID-19,” said Otten. “Their friends were taken away from them. Doing school all online is a very different experience than doing it in person. A lot of kids struggled with those kinds of things.”

In South Dakota, hospitals typically see a dip in youth admissions during the summer months. That has yet to happen this year.

“Our population has not dipped as much in the summer as usually we expect,” said Katy Sullivan, director of Monument Health Behavioral Health Center. “We expect youth admissions to decrease in summer, when they’re outside and not in school, but we’re not seeing that dip with our teen and child population.”

Mental health professionals say some South Dakotans have been coping with financial, physical and emotional tolls wrought by the pandemic on top of existing mental health conditions, and lingering stigma around seeking help could put more people’s mental health in jeopardy.

Deaths by suicide typically increase within two years of a natural disaster, which could include the pandemic that began in January 2020 and is still causing illnesses and deaths, said Bridget Swier, director of communications and outreach at the Front Porch Coalition, a suicide prevention and support group in Pennington County.

“Generally, when a natural disaster hits, the community rallies together, neighbors help each other out, and we find ways to help each other. That sense of community was strong during the pandemic, but toward the end, as people go back to their lives, that sense of togetherness isn’t as strong,” Swier said. “I think we’re just beginning to see long-lasting impacts in regard to mental health.”

Now that people in South Dakota and across the country are re-entering into what many consider a “normal life” in the post-pandemic era, the transition can be difficult for people who experienced any kind of loss during the pandemic, such as losing a job, losing a loved one to COVID-19 or losing friends over political arguments.

“We can’t expect people to go back to living like it’s 2019,” said Sheri Nelson, Suicide Prevention Director at the Helpline Center.

The jump in suicides in the winter months of January through March in South Dakota is somewhat unusual compared to typical patterns of depression, one expert said.

Suicide deaths typically increase in the springtime and taper off in the summer, experts said. There are psychological and physical aspects to the spring that can exacerbate mental health conditions. Spring is usually a time for rejuvenation after a long, cold winter. But for people with mental health concerns, seeing others enjoy a fresh start may make them feel even worse for not being happier after winter.

“Those who may have spent the winter depressed find themselves, in the spring, still depressed, but with the energy and motivation to take their own life,” Adam Kaplin, Johns Hopkins psychiatrist, said in a recent Johns Hopkins publication.

Deaths by suicide across the nation decreased last year. According to preliminary statistics published by the National Center for Health Statistics in March 2021, there were 44,814 suicides reported in 2020, compared with 47,511 in 2019 and 48,344 in 2018.

Detailed national data about suicide deaths and attempts usually lag about two years behind the current date, but smaller-scale studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that more people were showing symptoms of depression or anxiety and having suicidal thoughts last year, despite a decrease in the number of suicides.

A CDC study released in August 2020, however, showed that 10% of people said they had suicidal thoughts within the past 30 days. In 2018, a similar survey found that 4% of people said they had considered suicide in the previous 12 months.

Even though nationally fewer people were reported to have died by suicide last year, experts say that doesn’t indicate a decrease in rates of suicidal thoughts or other mental health issues.

“There wasn’t a dip in suicidality. There was a dip in reports and people coming into the hospital,” Sullivan said. “More people were trying to deal with things on their own. They didn’t want to come to the hospital and risk an exposure to COVID-19.”

More healthcare professionals were in need of mental health aid over the last year and a half, advocates said. Medical professionals already had higher rates of suicide risk than most other professions before the pandemic. That risk was exacerbated by increased workloads and fear of COVID-19 infection. Because of that increased risk, Avera recently started a hotline specific to healthcare professionals, where any healthcare worker can get free confidential conversations over the phone.

Many who called into the Helpline Center said they didn’t want to burden friends or family with their problems, Nelson said. That and a negative stigma around receiving help for mental health issues could have contributed to the decrease in people who reached out.

Negative stigma around mental health and suicide is particulary strong in the Midwest, Swier said. The stigmatization often prevents people from seeking help, especially men in their 40s, one of the most prevalent groups of people who die by suicide in South Dakota.

“We’re hard workers. We pull ourselves up by our bootstraps. We don’t talk about our feelings and we get our work done,” Swier said. “If there’s stigma, who is going to be comfortable saying, ‘I’m having a tough time?’”

Swier said individuals who want to be supportive can educate themselves on the warning signs of suicide and support suicide prevention organizations. Suicide prevention is “everyone’s business,” Swier said.

“If you are struggling, it’s OK to reach out and get help,” Nelson said. “There is help out there. It’s normal to talk about mental illness, to talk about addiction, to talk about suicide. We want to get rid of that stigma so people will come forward.”

How to get help in a crisis

Here are some resources to get help for yourself or someone else who may be considering suicide.

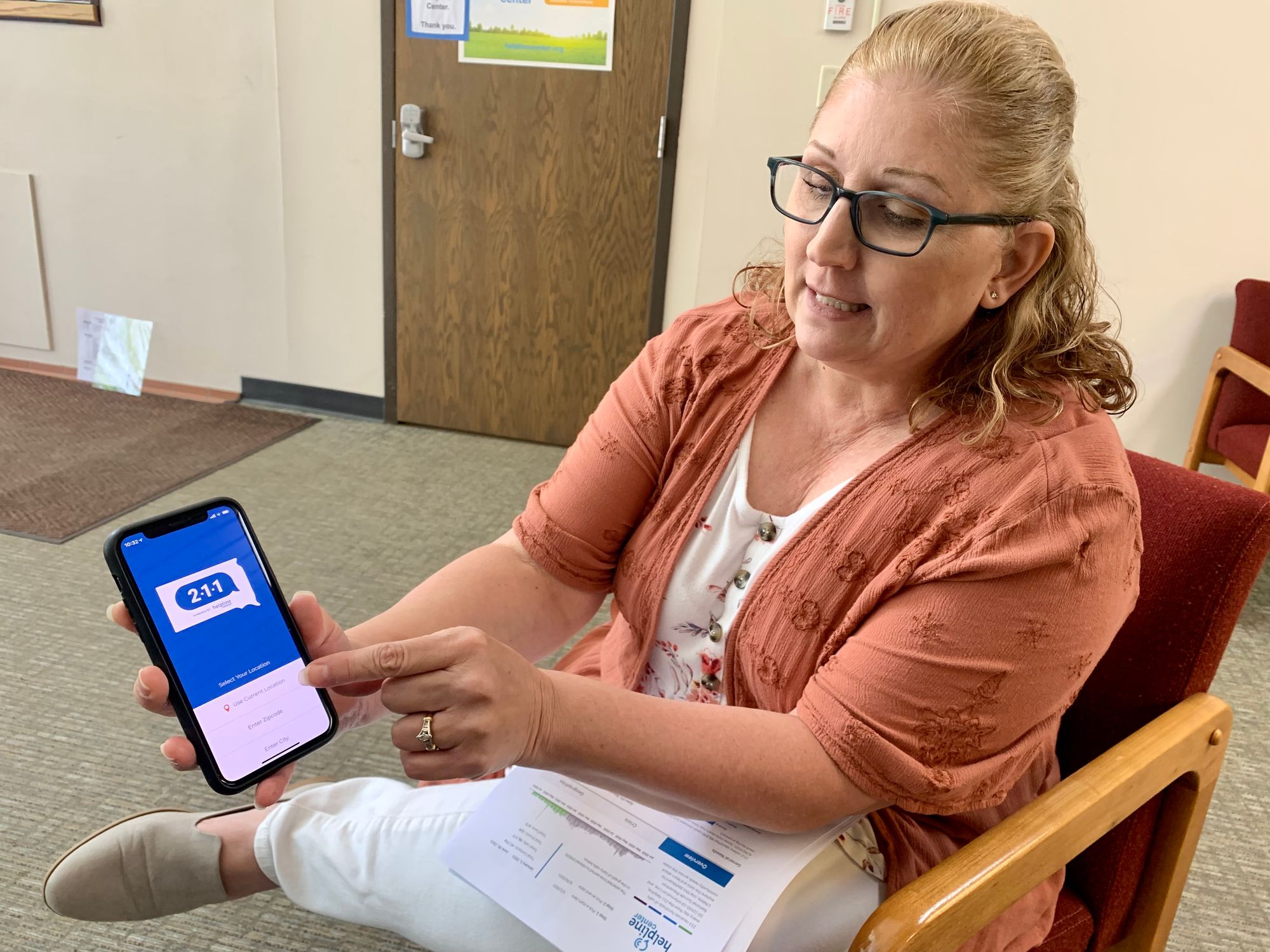

The Helpline Center: Callers across the state can obtain county-specific resource information and be connected to a suicide hotline. Call: 211 or 1-800-273-8255 or text your ZIP Code to 898211.

Front Porch Coalition: 605-348-6692

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255 (TALK)

Crisis Text Line: Text CONNECT to 741741

Trans Lifeline: 1-877-565-8860

The Trevor Project: 1-866-488-7386 or text START to 678678