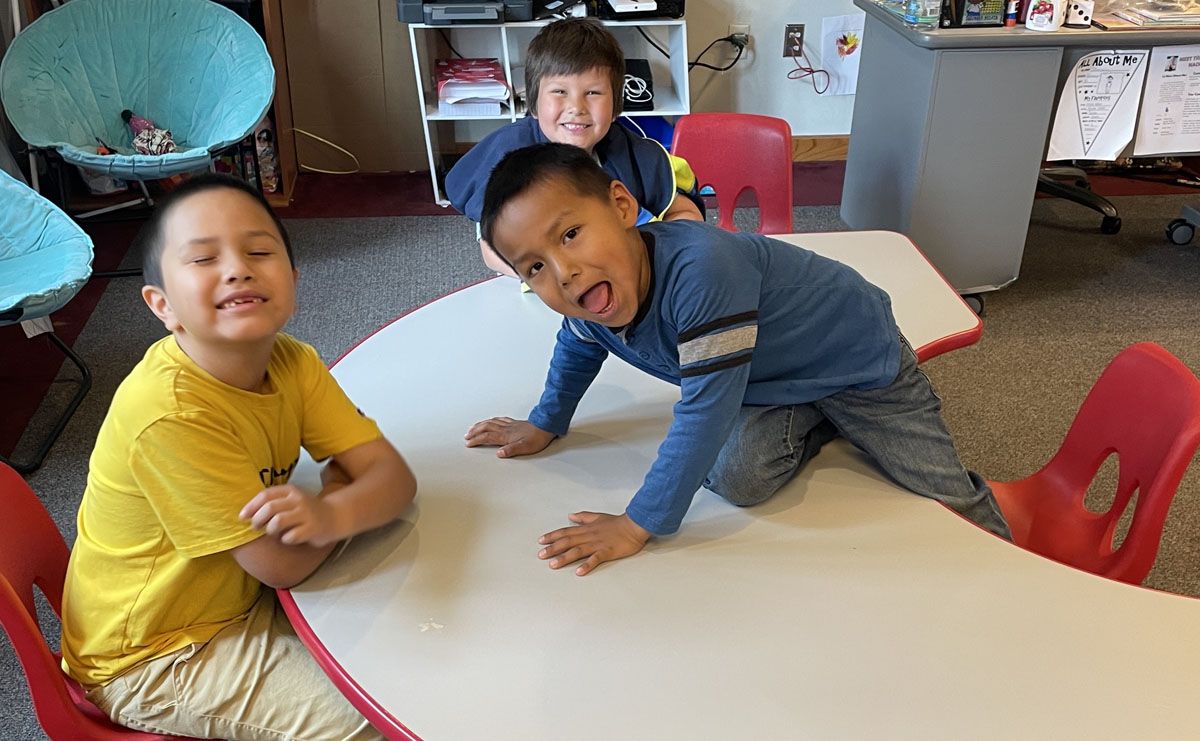

RAPID CITY, S.D. — Early mornings at the new Oceti Sakowin Community Academy are a joyous time for the roughly 28 kindergartners who attend and the two staff members who teach them.

Before classes begin, students join in a circle and sing the “Four Directions” song in Lakota, and students shake one another’s hands and share a positive greeting to promote kinship. Meanwhile, head of school Mary Bowman recites uplifting messages to show gratitude for the day, such as, “Remember, I am beautiful inside and out,” and “I am a sacred being.”

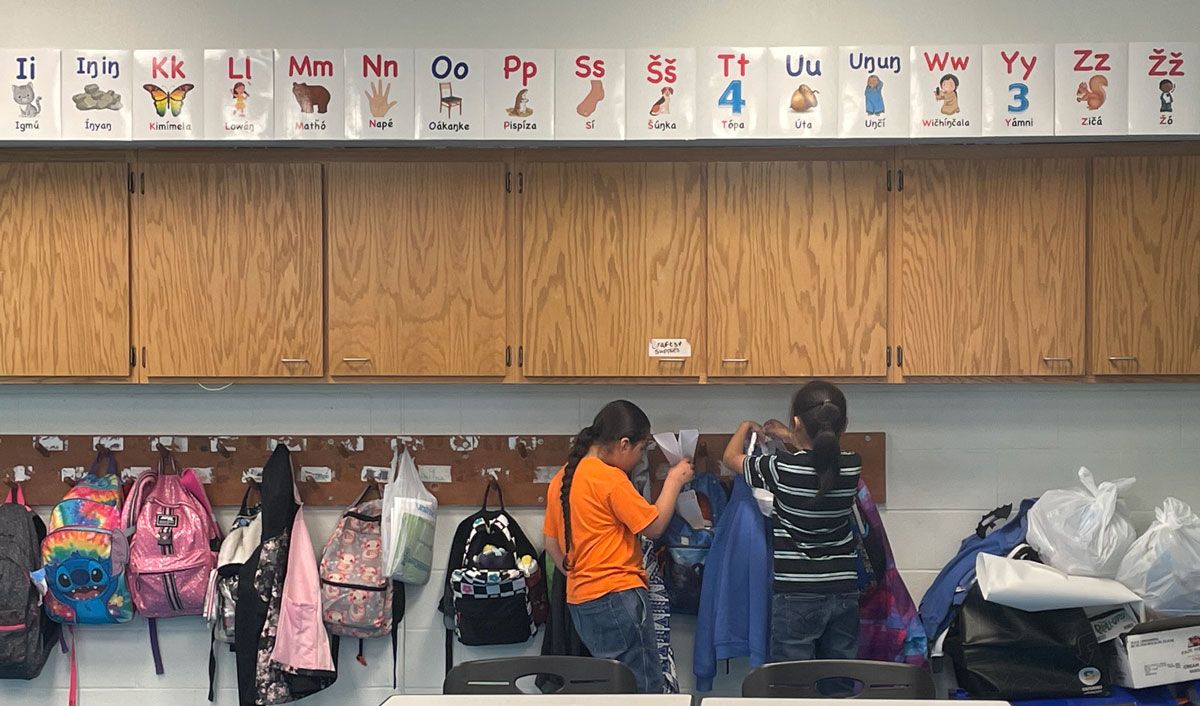

When they go inside, students sit among walls adorned with Lakota numbers, letters and translations. They are taught lessons from books by Native authors and which feature Native folk tales and spiritual messages. The school employs “restorative justice” when behavior problems pop up, giving students time to cool down and then asking them to apologize to anyone offended. Kinship is encouraged among students, who often refer to one another as cousins.

The school, funded with private money, completes its first year of operation in late May. It is the latest among several ongoing efforts to improve Native education in the state outside the traditional public K-12 school system.

The academy and other schools using Native culture as a foundation for learning are part of a trend in which Native American educators in South Dakota are no longer waiting on state government or the Legislature to improve teaching and learning for Native students, who have trailed their white peers in every academic measure for generations.

Bowman said the model for teaching at the academy “is basically the same as how our ancestors did it.”

“We really believe in nurturing the whole child, and that if they have that strong nurturing, the academics will come with it,” she said. Students develop a strong belief and confidence in who they are, and a keen awareness that they belong. Those feelings, Bowman said, will “remind students that they have an inherent indigenous genius.”

Community academy has big expansion plans

The Oceti academy taught only kindergartners in a local church in its first year. But it has big plans to expand grade offerings each year and eventually move onto a 40-acre campus in north Rapid City with multiple buildings, a cultural center and affordable housing units.

At the school, students are taught essential Lakota beliefs, including that communities work best when they work together, and that all things, alive or not, are of critical importance to the world and deserving of care and respect.

On a recent field trip, students were taken to several nearby sacred Native sites, including to the area below Black Elk Peak, to Bear Butte and to Pe Sla, a spiritual site in the Black Hills. In preparation, they engaged in oral storytelling through a tale about Lakota spiritualism and discovery, and Bowman said some students are able to recite parts of the story by heart.

Like other culturally based Native schools in South Dakota, the academy infuses lesson plans and the learning environment with Lakota language, indigenous beliefs and a staff that tries to foster confidence and self-determination within students.

The academy joins a small cadre of privately funded Indian schools in South Dakota. Others include Red Cloud Indian School and Anpo Wicahpi girls school in Pine Ridge, St. Joseph’s Indian School in Chamberlain and Wakanyeja Tokeyahci School in Mission, which opened in 2020 and where students are taught only in the Lakota language.

The new academies in Rapid City and Mission and other Indian schools use evidence-based, culturally focused teaching methods, curricula and environments aimed at improving Native student performance.

A potential path to prosperity

Improving academic performance among Native children is intended to create a path to prosperity for a population that has for generations faced numerous social and socioeconomic challenges. It also has long battled high youth and adult suicide rates, incarceration levels and incidence of substance abuse. Native Americans in the U.S. have faced years of oppression and historical traumas, from being moved onto reservations to the forced assimilation implemented at boarding schools.

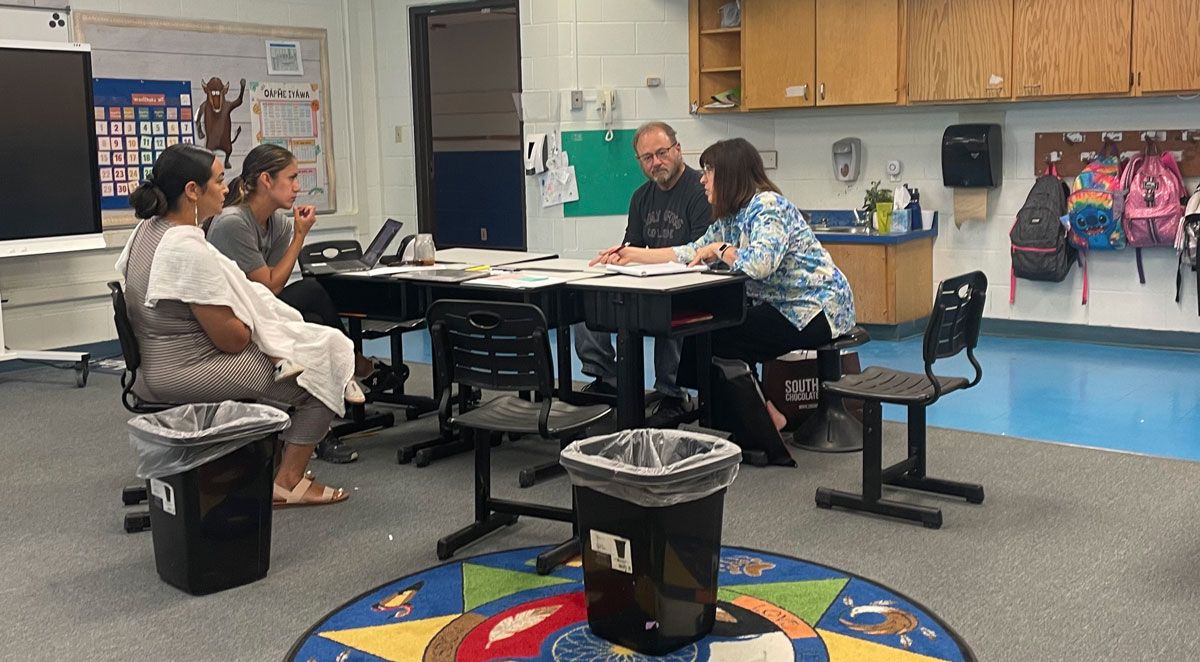

The Oceti academy is designed within the framework of the NACA Inspired Schools Network (NISN), a national nonprofit that “supports leaders in Indigenous communities to develop a network of schools providing rigorous academic curriculum aimed at college preparation while also promoting Indigenous culture, identity, and community investment.”

More from News Watch: As Native students continue to struggle in S.D. schools, a Lakota-immersion model emerges

In year one, the school had a goal of raising $1 million in its first year but fell short, despite significant funding from NISN and the NDN Collective in Rapid City, a group that raises funds and develops programming to enhance Native life, culture and activism in the region.

Attendance at the school is free, and enrollees can be Native or non-Native. The per-child cost at the academy is about $25,000, well above the roughly $11,000 per-student cost in the public school system. Money donated to the academy will also be used to expand enrollment per grade and add a new grade level each year, with sufficient staffing, Bowman said.

Next year, the school will move to a modular building on a site on North Haines Avenue in Rapid City where a campus will eventually be built to accommodate an educational community, she said.

South Dakota ‘is going backwards in this effort’

The new schools, according to Native leaders such as former state senator Troy Heinert, are a partial response to the repeated failure of the Legislature to allow a pilot project in which public funds would be used to open two to four charter schools centered on Native culture and language. Numerous studies and results from culturally based schools in South Dakota and across the U.S. have shown that increasing the focus on Native culture, language and history can improve learning.

“It seems like our state is going backwards in this effort,” said Heinert, a Democrat who led three unsuccessful attempts to get legislative approval for Native-based charter schools.

“What we’re up against is the status quo, the thinking that it’s OK where our Native test scores are, that it’s OK where our Native attendance rates have been. The students don’t feel like they have a place in the majority of South Dakota school systems,” Heinert said.

Native achievement falters in public schools

Academic achievement for white students in South Dakota is far from stellar compared to some other states. It’s much worse for Native and other minority students in every metric, including subject proficiency levels, number of students ready for college or a career, and rates of school attendance and graduation. South Dakota has about 137,000 students in the public school system, of which roughly 98,000 (72%) are white and 14,000 (11%) are Native.

According to the 2021-2022 South Dakota Report Card published by the state Department of Education, white students were 58% proficient in English, 50% proficient in math and 49% proficient in science. The data show that 21% of Native students were proficient in English, 12% proficient in math and 13% proficient in science last year.

While 95% of white students graduated, 69% of Native students completed high school. And while 58% of white students were considered college or career ready upon graduation, only 13% of Native students were prepared, a rate that was lower than for students classified as homeless (19%).

Perhaps most concerning, however, is the gap in attendance and absenteeism between white and Native students. While 92% of white students attended daily, 56% of Native students attended daily. And as 14% of white students were considered chronically absent (missing 15 or more school days a year), 53% of Native students were labeled chronically absent.

Many academic measures fell for all students in South Dakota during the pandemic years of 2019-2021. But the upheaval landed harder on Native students who, often for socioeconomic reasons, were less equipped to manage their schooling during COVID-19.

Education secretary applauds Native schools

The South Dakota Department of Education declined an interview request. But Secretary of Education Joseph Graves said in a statement to News Watch that the department supports the new schools that have opened recently to help Native students.

“The Department of Education is absolutely supportive of the grassroots efforts within the Native American community to seize their own educational destiny and will work hard to support those efforts as we can. The blooming of such schools and programs is a promising and exciting development,” Graves wrote.

In recent years, the state has tried to address the Native achievement gap through programming to reduce teacher shortages in schools with high Native populations. It developed the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings, a template for teaching Native culture in public schools. Graves added that the DOE and Gov. Kristi Noem supported the Native charter school bills that failed.

The Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings are a set of state-approved concepts that provides a framework for teaching Native history and culture. The 35-page set of lesson plans and instructional guidelines includes teaching aids in history, culture, language, treaties, identity and way of life of Lakota, Dakota and Nakota Sioux Indians.

However, use of the Oceti understandings is voluntary in South Dakota school districts.

A 2021 state survey of more than 700 educators in 125 school districts found that only 45% of educators reported using the Oceti understandings in their schools. Nearly 1 in 10 educators said their schools did not celebrate Native history or culture at all.

The Native charter school legislation was opposed by several education associations in the state, which are against charter schools in general because they can siphon money away from public schools and can open the door to lightly regulated schools potentially with unorthodox curricula.

Some opponents also highlighted ongoing culturally based programming in public schools, including a Spanish-language program at Sonia Sotomayor Elementary in Sioux Falls and a Native-centered class at Canyon Lake Elementary School in Rapid City. However, the class in Rapid City was halted after one year due to staffing challenges.

Lakota language seen as essential to learning

One major tenet of improving Native education, and learning for ethnic minorities in general, is teaching of languages beyond English. Language, experts say, is a critical component of enhancing culture, and boosting cultural awareness and confidence among minority students creates a stronger foundation for learning.

Native immersion schools across the U.S., such as those based on a model developed at the Native American Community Academy in New Mexico, have seen improved graduation rates and academic achievement for Native students.

Fully immersive Lakota schools teach courses entirely in Lakota, while most culturally based schools in South Dakota use dual-language methods that include use of English and Lakota in classes in addition to infusing Native cultural and spiritualism into curricula.

Dual-language learning provides academic benefits both to majority and minority students, according to research by Elena Sada, a researcher at Boston University. Students exposed to dual-language learning outperformed their single-language peers by as many as 22 points on standardized tests and obtained the equivalent of eight months of additional learning, Sada’s research showed.

Those findings have proven true at Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, where dual-language courses have been taught for years and a full Lakota immersion program has been in place for about six years, according to Matthew Rama, who runs the immersion program at Red Cloud.

Based on Measures of Academic Progress testing, students in full immersion classes have tested the same or higher than prior to being taught in Lakota, and a handful of immersion students have far outpaced their dual-language peers on tests taken in English, Rama wrote to News Watch.

Rama also pointed out that a 2023 White House report on Native education indicated that proficiency in Native languages contributes to the overall health and wellbeing of Native individuals and their communities, improved socioeconomic status and “overall richness of life.”

‘Everything comes from the Lakota perspective’

Maggie McGhee has spent five years learning the Lakota language and the past three years teaching it at Red Cloud school. McGhee, 30, is an indigenous woman who grew up in South Dakota and graduated from White River High School, where she said she was treated well but still never felt like she fit in or was able to reach her full potential.

“I was always in a state where I was uncertain or couldn’t feel calm or relaxed,” she said.

While the entire campus of Red Cloud school is Christian-based and focused on Native history and traditions, the full immersion classes taught by McGhee and others aim to strengthen Lakota culture even further.

“Our belief is that you can’t teach the culture without language and vice versa,” she said. “Everything we do here comes from the Lakota perspective, and we use indigenous pedagogy (teaching) to steer our curriculum and lesson plans, and in this class, Lakota language is a big part of that.”

Students are taught to live and learn via the seven Lakota values, which include fortitude, generosity, kinship, prayer, respect, wisdom and compassion.

The school and its staff create a welcoming environment for Native and non-Native students, many who come from families facing economic and social challenges in the Pine Ridge region, she said.

On the final day of the school year in mid-May, students at the school were ebullient and a sense of informality predominated.

As McGhee spoke with a visitor, a young boy brought an armful of root beer floats and offered to share. Another student entered the room and, using only Lakota language, asked McGhee for a bag since he forgot his backpack at home.

“When they see themselves in the school, in the teachers and posters on the walls and curriculum that is being taught, they have greater academic success and their emotional development is better,” she said. “I see our students become confident in who they are, with a strong identity, and they’re able to grow up and face any obstacle in life.”

McGhee believes the public school system in South Dakota can take “baby steps” to improve education of Native students, but only “if people are willing to do the work.”

First, the larger education system needs to do better at communicating with Native families and providing “wraparound” services outside the schools to nurture families and create greater stability at home.

“We always put the child first and believe we can worry about things in the classroom second because how are you going to bump up test scores if their basic needs aren’t being met,” she said.

Then, more educators and officials must understand that creating a welcoming learning environment takes more effort than just being kind; that instead they must learn and better appreciate the positive elements of Native culture and understand a sometimes harrowing history, and then communicate to students that they are welcomed and appreciated through that lens.

Finally, Native culture can be integrated more frequently into the curricula so indigenous students feel part of the larger educational conversation in schools.

“We have such a huge indigenous population in South Dakota that I hope that someday it will happen,” she said.