The Lewis & Clark Regional Water System, which serves Sioux Falls and other population centers in eastern South Dakota, has received a record amount of federal funding at just the right time to accommodate surging populations and drought conditions.

The new money will move the original system closer to full completion while also making possible expansion that is crucial in the processing and delivery of fresh water to much of southeastern South Dakota.

Tapping into an aquifer adjacent to the Missouri River south of Vermillion, the wholesale provider serves 15 community members in South Dakota, Iowa and Minnesota – including Sioux Falls and neighboring cities Harrisburg, Lennox and Tea. Though Sioux Falls has other water sources such as the Big Sioux Aquifer, smaller cities that rely solely on Lewis & Clark such as Beresford, Centerville and Parker exceeded their expected amount of water usage last summer.

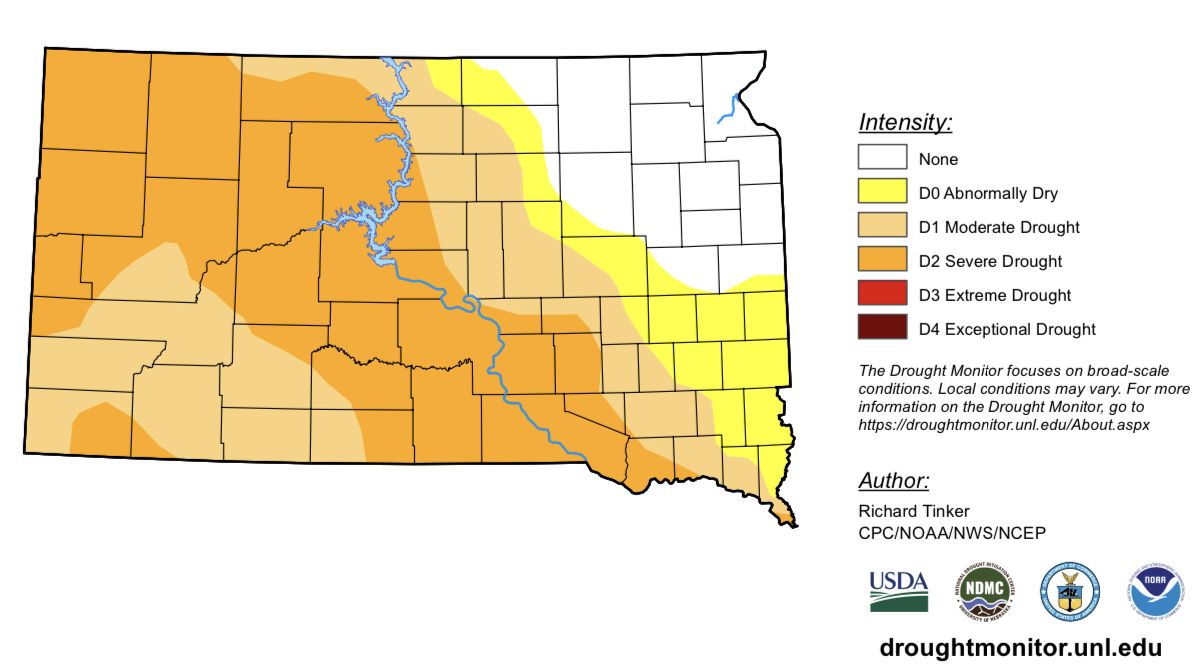

That increase in demand could challenge the system’s ability to collect, treat and deliver water for residential and agricultural use at a time when nearly half of South Dakota faces either severe or extreme drought conditions, according to data from the National Drought Mitigation Center.

The enhanced system that Lewis & Clark has been trying to complete since breaking ground in 2003 – which treats the water and stores it in wells before distributing it through pipelines – would deliver a total of 44.1 million gallons a day to its members and reach an estimated 350,000 people. But that project is not yet complete.

Last year, Lewis & Clark ran at a maximum capacity of 32.2 million gallons a day and came close to hitting that amount of usage during the summer months, forcing administrators to consider throttling back distribution.

“We put out a plea to members to voluntarily reduce their consumption to the degree they were able,” said Troy Larson, director of the water system. “Their collective efforts brought us back from the brink.”

Beyond completing the original blueprint, which could happen in the next few years, expansion of the system is already planned, with increased storage and the goal of pushing capacity to 60 million gallons a day by 2030, a project funded by the system’s members.

“That expansion is driven by the drought,” said Larson. “But just because we’re starting it now doesn’t mean it will be done tomorrow. It’s not a phased deal. Until we finish, there won’t be an additional drop of water beyond those (44.1 million) gallons.”

That could make for an interesting summer, especially with construction of a new collector well near the Missouri River south of Vermillion slowed by shipping delays. The well, built to extract and process groundwater from the aquifer, was scheduled to be completed in early June but could now stretch into September, adding stress not just on residential use but agricultural and economic development.

Jesse Fonkert, president and CEO of the Sioux Metro Growth Alliance, said his group has had to turn away several agriculture-based development projects in the Sioux Falls area over the past year because of the inability to meet large-scale water demands.

“There are several that we got to the final stage on, but the water component is key,” said Fonkert. “The state is doing a good job of going out and recruiting these projects, but the challenge locally is having enough land and utility to seal the deal.”

Infrastructure package provides boost

Ever since the Lewis & Clark system received congressional authorization in 2000, federal funding has dictated the pace of construction, keeping some communities waiting for service. The spigot of spending slowed considerably after an earmark ban was passed in 2011, preventing Congress from allocating a certain amount of money for a specific project. That led to seven consecutive years, from 2011 to 2017, of Lewis & Clark receiving less than $10 million to add pipeline, reservoirs and pump stations to the project.

“We were struggling mightily to make any progress at all,” said Larson, who closely followed legislative efforts to pass a major infrastructure package in Washington following the 2021 reinstatement of earmarks with new safeguards.

The vision became reality last November, when President Joe Biden signed a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure law that led to a record $75 million investment in the Lewis & Clark project for fiscal year 2022 through the Bureau of Reclamation.

That will allow service to be extended to Madison in South Dakota, as well as northwest Iowa communities such as Hull, Sioux Center and Sheldon, meaning the original blueprint (with more infrastructure funding likely in the next two years) could be completed by 2025.

“I remember when I was hired (in 2003) going to Sheldon and Sibley and Madison and not being able to tell them what decade they would get water, let alone what year,” said Larson. “I would like to say that it was drought or momentum that made the difference, but the stars finally aligned with the political will to pass an infrastructure bill. It was a game-changer for us.”

South Dakota senators John Thune and Mike Rounds, both Republicans, voted against the infrastructure measure, though they worked early in the process to get projects such as Lewis & Clark included. Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, voted against it, while Chuck Grassley was one of 19 Republican senators who supported it. In the House, Republican South Dakota Rep. Dusty Johnson voted against it, calling the bill’s overall spending “unsustainable,” an opinion echoed by Thune in a statement following his vote.

“I have said from the very beginning that this bill should be fully paid for, and unfortunately, that is not the case,” said Thune. “While I support investments in our nation’s infrastructure, I could not support this final product that will further increase the national debt and financially burden future generations.”

Another federal stimulus package, the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan signed by Biden in March 2021, will boost Lewis & Clark’s expansion plans, which carry a price tag of about $100 million. The work was to be funded by members, a cost that gets passed to consumers, so states were asked to help defray those costs using ARPA funds.

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds recently announced $12 million in state ARPA funds that will complete that state’s commitment to the expansion project, while Lewis & Clark hopes to secure $350,000 from Minnesota for its more modest share of system infrastructure.

South Dakota, which Larson calls the “heart and lungs” of the project, was asked for $43 million for expansion and has allocated $13.1 million so far – part of $600 million of ARPA funds earmarked for local water and wastewater infrastructure grants. In all, the state’s Board of Water and Natural Resources recently approved $1.1 billion of funding in grants and loans for drinking water and wastewater projects, with more than 90 organizations receiving funding.

Preparing for the worst

There’s an old saying that whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting over. For David Ganje, a Rapid City lawyer who specializes in water and energy regulation, that sentiment rings particularly true during times of crisis, such as a drought.

Since Lewis & Clark relies heavily on public funding, Ganje has called for more accountability from the water provider on matters such as aquifer levels and priority of use for states and communities. Though the Missouri River is regarded by many as an inexhaustible resource, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has pointed to low levels in major reservoirs this spring and a decrease in power generation from dams.

Lewis & Clark uses 11 vertical wells that tap into the Elk Point Aquifer, hydraulically connected to and recharged by the Missouri River near Vermillion. Larson pointed out that water rights are granted by the state, with aquifer levels monitored by the South Dakota Geological Survey and the Department of Agriculture and National Resources.

But Ganje contends that “no water resource should be assumed to be inexhaustible,” calling for public analysis of which Lewis & Clark members have priority of water rights during times of drought and other emergencies, when shut-down orders can potentially occur.

“When you’re serving a contract between various government agencies and systems in different states, there needs to be a publicly available document regarding the priority of use in the event of shut down or reduced use,” said Ganje. “In the case of Lewis & Clark, I’ve never seen such a document.”

Larson said that type of agreement exists among members. If the system has to reduce the delivery of water, he said, it happens proportionally based on the amount each member is signed on to receive.

Such a scenario could occur this summer, if 2021 was any indication. Tea, a fast-growing community of about 7,000 residents just southwest of Sioux Falls, has a contract for 1.1 million gallons per day and reached 1.008 million gallons one day last June. The city averaged 837,461 million gallons a day that month, up from 433,706 in June of 2018.

Thad Konrad, Tea’s maintenance supervisor, said normal usage most of the year is about a third of capacity. But summer heat, especially in drought conditions, leads to heavy lawn watering in late July and August. The city has been a major advocate for Lewis & Clark expansion, of which Tea will receive a proportional amount.

“We’re concerned, but it’s not like people are going to run out of drinking water,” said Konrad. “A lot of it comes from a few people who dump 80,000 gallons a month on their yards. If everyone would just water normally, it wouldn’t be as much of a problem.”