Cooler spring temperatures, clouds and rain this year likely slowed South Dakota prairie rattlesnake activity. But as temperatures warm, they’re sure to make themselves seen — and heard.

“If you are almost stepping on it, you just jump in the air and do a dance. I mean, I think you could levitate,” said Black Hawk resident Shelby Nester.

Nester encountered his first rattlesnake of 2023 on May 10 when he joined Xtreme Dakota Bicycles on a group ride along Centennial Trail near Sturgis.

Nester said a biker spotted the rattlesnake on the side of the trail as he waited for the rest of the group to catch up. The snake did not slither off until the majority of the bikers passed.

Art: Native American artists in South Dakota travel new paths to prosperity

On May 25, Mindy Daley, who lives in Piedmont, was making her way down the Flume Trail near Rockerville when her friend pushed her out of a rattlesnake’s path. The snake didn’t rattle at her until she backed away.

“I was probably an inch or two from stepping on it,” she said.

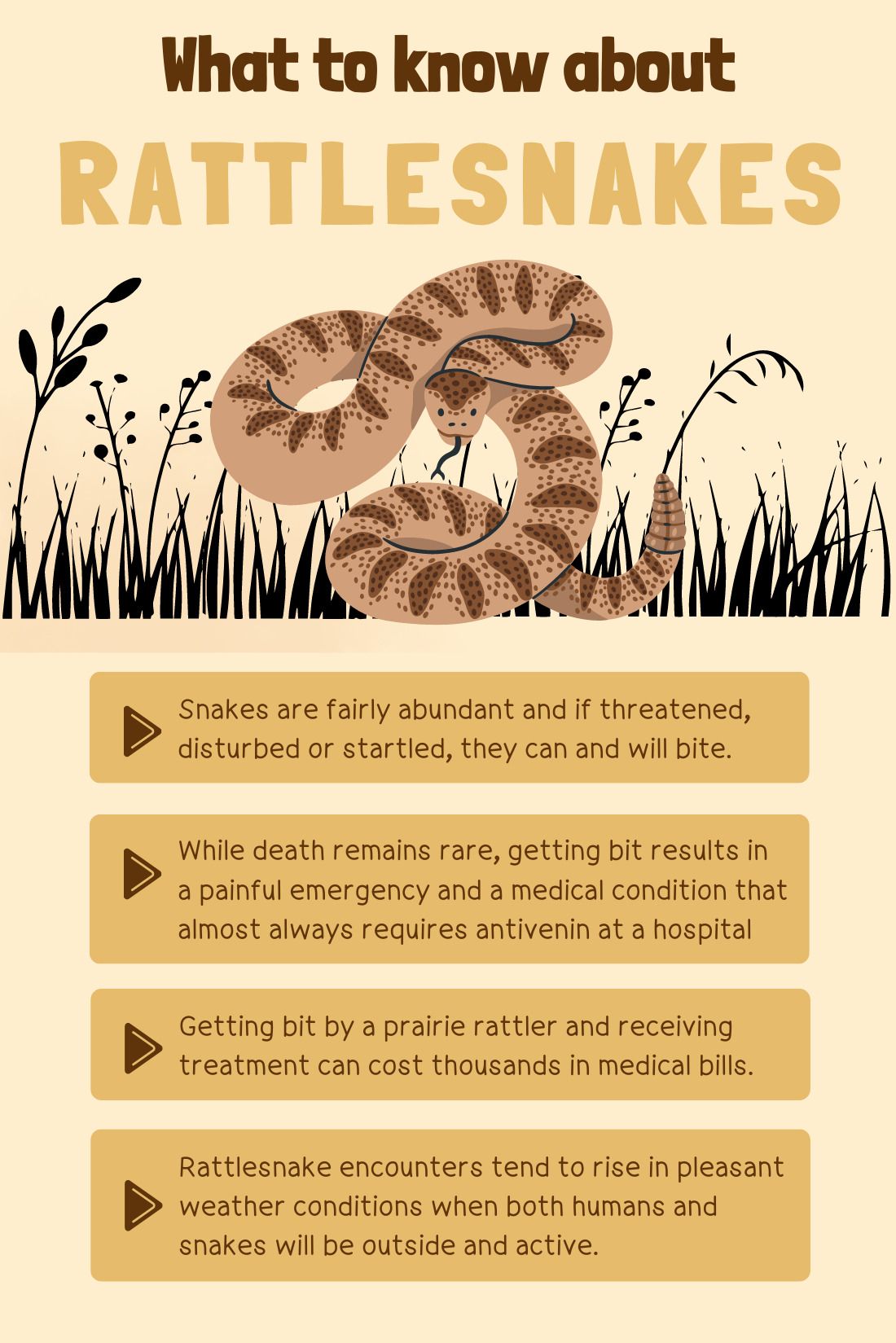

With rattlesnake season underway in South Dakota, snake experts say knowing more about prairie rattlers and their habits is the best way to avoid a bite.

South Dakota’s sole venomous snake

“Snakes like to be outside and active in the same temperatures people want to be out and active in,” said Terry Phillip, snake curator at Reptile Gardens outside of Rapid City.

The prairie rattlesnake inhabits grassy, rocky or wooded areas mainly west of the Missouri River but lives across the state. However, it is impossible to know exactly where people may encounter them, as adult snakes can travel up to 10 miles from their den in a hunt for prey or a mate, said Brian Smith, a Black Hills State University biology professor and snake expert.

Prairie rattlesnakes tend to be most active during the spring through the fall, but the animals are cool tolerant, he said.

“They will come out in fairly cool weather, like down to 50 degrees or more if they can get out and bask a little bit and warm their body temperature up,” Smith said.

Prairie rattlers can be found in both rural and urban areas, Phillip said.

“There’s not a corner or a neighborhood or a street in Rapid City where I haven’t been called in to capture a rattlesnake,” he said. “Near the hospital, on pavement downtown, at Canyon Lake Park or below M Hill. They’re found everywhere.”

Phillip said prairie rattlers will usually, but not always, emit a rattling sound to warn people and animals they are nearby. However, according to Smith, the snakes do always have rattles, even if they don’t always use them.

Typically, the snakes do not want to get near or bite any possible predators, including humans. But if annoyed or startled, the snakes that measure 20 to 30 inches can jut out a foot or more and bite.

Solid rattlesnake bite numbers are hard to come by

As of June 6, Dana Darger, Monument Health Rapid City Hospital’s director of pharmacy, said the hospital had seen at least one rattlesnake bite patient this year.

Avera St. Mary’s Hospital in Pierre and Avera Missouri River Health Center in Gettysburg have not had any snake bite patients in a few years, according to spokeswoman Sigrid Wald Swanson.

Without formal tracking of snake bites, concrete data are hard to come by. But in 2013, the state Department of Health performed a study showing that from 2000 through 2011, about 160 people were hospitalized due to venomous bites across the state.

Most bites took place in July, August and June. A majority occurred in counties west of and along the Missouri River, though five hospitalizations were reported in Minnehaha County, and four each in Yankton and Hughes counties during that 12-year time period.

Experts say the number of snakebites is vastly underreported because the bites receive little attention from media, and most victims recover quickly.

Across the United States, an estimated 7,000 to 8,000 snake bites are reported each year, and about five of those victims die, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Regardless of the current frequency in rattlesnake bites and encounters, an increase may await South Dakota in the future.

“The more we develop into the wild, the more access to the wild you’re going to have,” Phillip said. “The simple reality is that they’re there, so the further we go out, the more often you’re going to encounter wildlife, including mountain lions, bees and snakes.”

Prairie rattlesnake bites are rarely fatal

Bites from prairie rattlesnakes are rarely fatal in humans because the snakes are relatively small and do not possess the amount and potency of venom required to quickly kill a human, Smith said. The speed with which medical treatment can now be provided also helps keep fatalities low, he said.

“Lethal bites are very rare for this species. Most lethal bites in the country come from Eastern and Western rattlesnakes. Their range begins at least 1,000 miles from us,” Smith said.

Although Phillip and other snake experts say prairie rattlesnake bites are often the result of humans trying to kill or harass snakes, random encounters do occur:

- August 2014: A rattlesnake bit a 9-year-old boy from Black Hawk while he was walking to his campsite at Angostura Reservoir south of Hot Springs.

- August 2014: A rattlesnake bit a 2-year-old girl twice while she was playing in her family’s yard near Ellsworth Air Force Base in Box Elder.

- June 2018: One of the burros in Custer State Park died after a rattlesnake bit its face.

- June 2018: While out for an evening stroll in a prairie pasture in eastern Wyoming, a prairie rattlesnake bit Lead-resident Derek Livermont on the ankle.

- June 2018: 70-year-old Lawrence Walters of Geneseo, Illinois, died after a rattlesnake bit him on the ankle while he was golfing at Elkhorn Ridge Golf Club south of Spearfish.

While the snake’s venom contributed to Walters’ death, it was not the primary cause, according to Marty Goetsch, the Lawrence County Medical Examiner at the time who listed Walter’s cause of death as cardiac arrhythmia.

“If the rattlesnake hadn’t bitten him, he probably would not have passed away,” Goetsch said. “The individual had extensive heart issues and the rattlesnake bite was the beginning of a chain of events that unfortunately took his life.”

Hospitals are ready with antivenom

Most hospitals in South Dakota are well-positioned to help someone who has been bitten by a prairie rattlesnake.

According to Darger, Monument Health’s five West River hospitals carry roughly 120 vials of ANAVIP, an equine-derived antivenom. About 60 of those vials reside in Monument Health Rapid City Hospital while the rest are spread among the other four facilities in Sturgis, Custer, Lead-Deadwood and Spearfish.

Avera keeps 30 vials on hand at St. Mary’s in Pierre and 10 at Avera Missouri River Health Center in Gettysburg, Wald Swanson said. Physicians remain in contact and can move patients or the antivenom to any group hospital in an emergency, Wald Swanson said.

Wald Swanson said one dose of ANAVIP consists of 10 vials administered over the first hour. Patients may receive additional doses every hour until the progression of symptoms stabilizes.

The prairie rattler venom consists of digestive enzymes that attack tissue in the victim, Smith said. Common symptoms include pain and swelling in the area of the bite, numbness in the lips and mouth, nausea and lethargy.

Patient costs can be steep after rattlesnake bites

Like a lot of medical products, the markup for patients is high.

Darger, who used to see a regular stream of snakebite patients while working in Pierre, joked that, “I used to say to them, ‘If you get bit, leave me the keys for your Suburban.’”

The drug costs Monument Health about $1,200 per vial, and each vial has roughly a three-year shelf life. Darger said Monument Health hospitals rarely have to dispose of outdated antivenom.

Treatment of a snakebite victim, depending on severity, often includes emergency room entry, delivery of antivenom and a hospital stay of a couple days for observation, Darger said.

Livermont said his hospital bill for emergency treatment and two vials of an antivenom known as Crofab at what was then Regional Hospital in Spearfish was $27,000. Pharmaceuticals amounted to about $10,000 of that cost.

Hikers run into rattlesnakes in South Dakota

An avid biker and hiker, spring rattlesnake sightings aren’t unusual for Nester. On several occasions, he has glanced down during a bike ride and found a rattler coiled up in the middle of the trail.

Although he has run into a number of rattlesnakes in his 35 years in South Dakota, encountering the snakes still manages to instill a jolt of fear in him.

“Well, it’ll make your heart stop for a second or four,” Nester said with a laugh.

At the start of June, Nester found two rattlesnakes on a gravel road that had died after a vehicle struck them.

After moving to South Dakota in 2020, Daley said she accumulated hundreds of miles on the trails as she prepared for the Black Hills 100’s 50K. During those miles of outdoor training, she never ran into a rattlesnake.

“If I saw one, I think I would react a little differently. But the fact that I almost stepped on it and I didn’t see it — and I hike a lot — is scary to me,” Daley said.

Daley lives in a development in Piedmont. When she came home from her rattlesnake encounter, she received a message that said a rattlesnake was on her neighbor’s driveway.

While Daley normally scans the ground as she hikes, she said she’ll be more cautious on future excursions.

“Just be aware of your surroundings and aware of how you would get out. And thank God for my friend. I would’ve just walked by it, which means I would’ve sat there for who knows how long,” Daley said.

With his first rattlesnake sighting of 2023 checked off, Nester plans to practice several safety precautions, like wearing boots and watching where he walks.

“I don’t alter what I do because of them. But I definitely am pretty cautious if I’m stepping off trails, especially in grass where I really can’t see what’s below me,” he said.