SCOTLAND, S.D. – On a foggy day in September 2015, the quiet solitude of a Bon Homme County farm was interrupted by crashing rail cars and the ignition of thousands of gallons of ethanol.

According to the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Railroad Administration reports, the 6,044-foot long train with three locomotives, two buffer cars and 96 tankers loaded with ethanol from the Glacial Lakes Energy Company plant in Mina, S.D. left Scotland at 5:43 a.m. on Sept. 19, 2015. The train, operated by the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railroad, was headed southeast to Sioux City, Iowa and eventually to the Valero Energy Corp. plant in Deer Park, Texas.

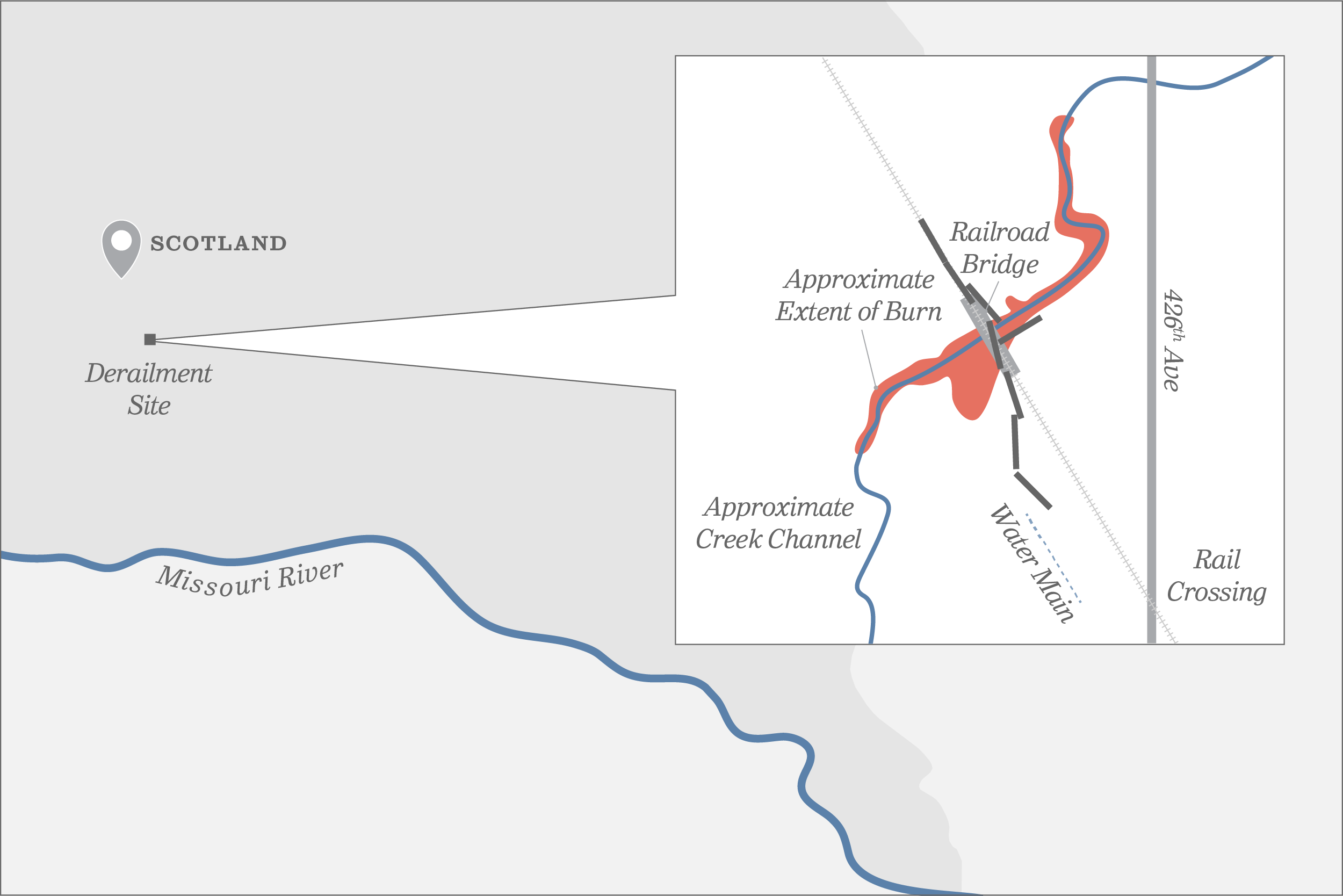

The conductor and engineer piloted the train at 10 mph in heavy fog and initially had an uneventful trip. But just after the lead locomotive crossed the railroad bridge over Prairie Creek — a wooden structure built in 1954 — the train derailed. An automatic emergency brake applied and the train traveled another 80 feet before stopping. The two conductors reported the derailment and fire and fled the locomotive safely. They returned a short time later to disconnect the locomotives and drive them a safe distance from the fire. Both crew members were ruled to have been fatigued, but both tested negative for drugs or alcohol.

A fire crew from Scotland made it to the scene in 10 minutes and the Lesterville Fire Department was called shortly thereafter.

Seven tank cars, in positions 4 through 10 near the front of the train, derailed and three of them were breached, spilling 49,743 gallons of ethanol. The resulting fire extended about 250 feet to the south of the track and 350 feet to the north, generally following the mostly dry creek bed. The railroad bridge was destroyed.

Both the Federal Railroad Administration and the National Traffic Safety Board ruled that a broken rail line was the ultimate cause of the derailment. However, the NTSB, which has no regulatory authority, went further in its conclusions, ruling also that:

- BNSF was responsible for deferring needed safety improvements by reducing the safety classification of the rail line, which also allowed the company to continue to carry hazardous materials train cars on that line without the fixes.

- FRA regulations were at fault by allowing rail companies to operate hazardous material tankers on lines upon which rail companies have downgraded the safety classification.

- Finally, the NTSB ruled that the continued use of older DOT-111 tanker cars that are more prone to puncture was a contributing factor to the accident and fire. Those older tanker cars, owned by companies that ship by rail, will be phased out completely over the next seven years in favor of DOT-117 cars that have internal safety barriers and are more resistant to breaching during derailment.

In concluding its report, NTSB made two recommendations to the FRA and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. The agency recommended heightened safety reporting requirements to document the increased derailment risk associated with older, weaker tracks and with the continued use of older DOT-111 tank cars. The agency also urged federal regulators to record more data on where hazardous materials will be routed, and urged that the weight of the tanker cars in relation to the strength of the rail lines be included in future safety assessments.

In a response on behalf of both regulatory agencies, acting PHMSA administrator Drue Pearce wrote on Oct. 19, 2017, that the agencies do not concur with the recommendations. He said adding more reporting requirements would be redundant of existing safety analyses, and would “substantially change key programming that would increase costs to their (rail companies) subscribers.”

In his response, Pearce pointed to a new set of regulations set forth by the two agencies in May, 2015, in which 27 safety factors must be considered when routing high-hazard flammable materials. Furthermore, the FRA in 2015 launched a crude oil track examination program that includes an intensive 2-week inspection of crude oil lines and transport processes, and a requirement that crude oil trains have enhanced braking systems on high-hazard trains by 2021.

After the 2015 accident, BNSF paid a contractor, Pinnacle Engineering of Minneapolis, to do the materials testing and remediation of the spill. The company used a system known as air sprage/soil vapor extraction to expose the soil and water to the air in order to eliminate the contaminants.

Test results show the remediation has gone well and that the small amount of remaining chemicals in the ground water is stable, said Brian Walsh, a South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources Environmental Sciences Manager. He said the state’s review of the remediation plan has shown that no human lives are threatened from the chemicals released.

According to state reports, the spill led to the release of several chemicals, including the 49,743 gallons of ethanol as well as the carcinogenic compound benzyne and its derivatives ethylbenzene, toluene and xylene. All five compounds were found in the soil, and all except ethylbenzene were found in the groundwater. Walsh said the compounds were released only into a small quantity of ground water, and have since been cleaned up.

Walsh also pointed out that the clean-up has not received the state’s full “no further action required” sign-off because the property owner is in a dispute with the rail company and will not allow inspectors on the site for a final soil and water test. “We are in a little bit of limbo,” he said. “There’s no identified risks, there’s just a very small amount of groundwater that was contaminated.”

Walsh said the rural location where the spill took place mitigated its impact on people.

“An ethanol spill in a farm field where there are no wells or people around, it’s never good but it’s safer than if it happens in a populated area,” he said.

But from the standpoint of farmer Mike Neth, on whose land the 2015 derailment and fire took place, the fallout from the accident has been significant.

Neth said that when BNSF rebuilt the wooden bridge destroyed in the fire, they installed a culvert system that prevents him and his son from moving cattle along Prairie Creek onto about five acres of grazing land on the other side of the bridge.

“It’s like building a wall through your backyard,” Neth said. “We’ve got five acres that won’t ever be productive again.”

Neth said he asked BNSF for a $90,000 settlement for his time, loss of land access and the loss of fill dirt that was contaminated, but that the company has rejected his claims. “It’s put a hardship on us,” he said. “It’s affected my son’s income and mine.”

BNSF spokeswoman Amy McBeth said in a statement to News Watch that the company wants to work with Neth to satisfy his claims.

“We’ve been working with the landowner, making a more than reasonable offer to address the impact and his concerns. We remain hopeful we can reach an agreement,” McBeth wrote.