CUSTER STATE PARK, S.D. — Just before nightfall on Tuesday, Dec. 12, 2017, wind gusts up to 60 mph whipped a fairly typical Black Hills wildfire into a multi-front blaze that suddenly jumped the fence around Custer State Park. It headed directly toward ranches, the four-lane U.S. Highway 79, and about 100 homes in the small towns of Fairburn and Buffalo Gap.

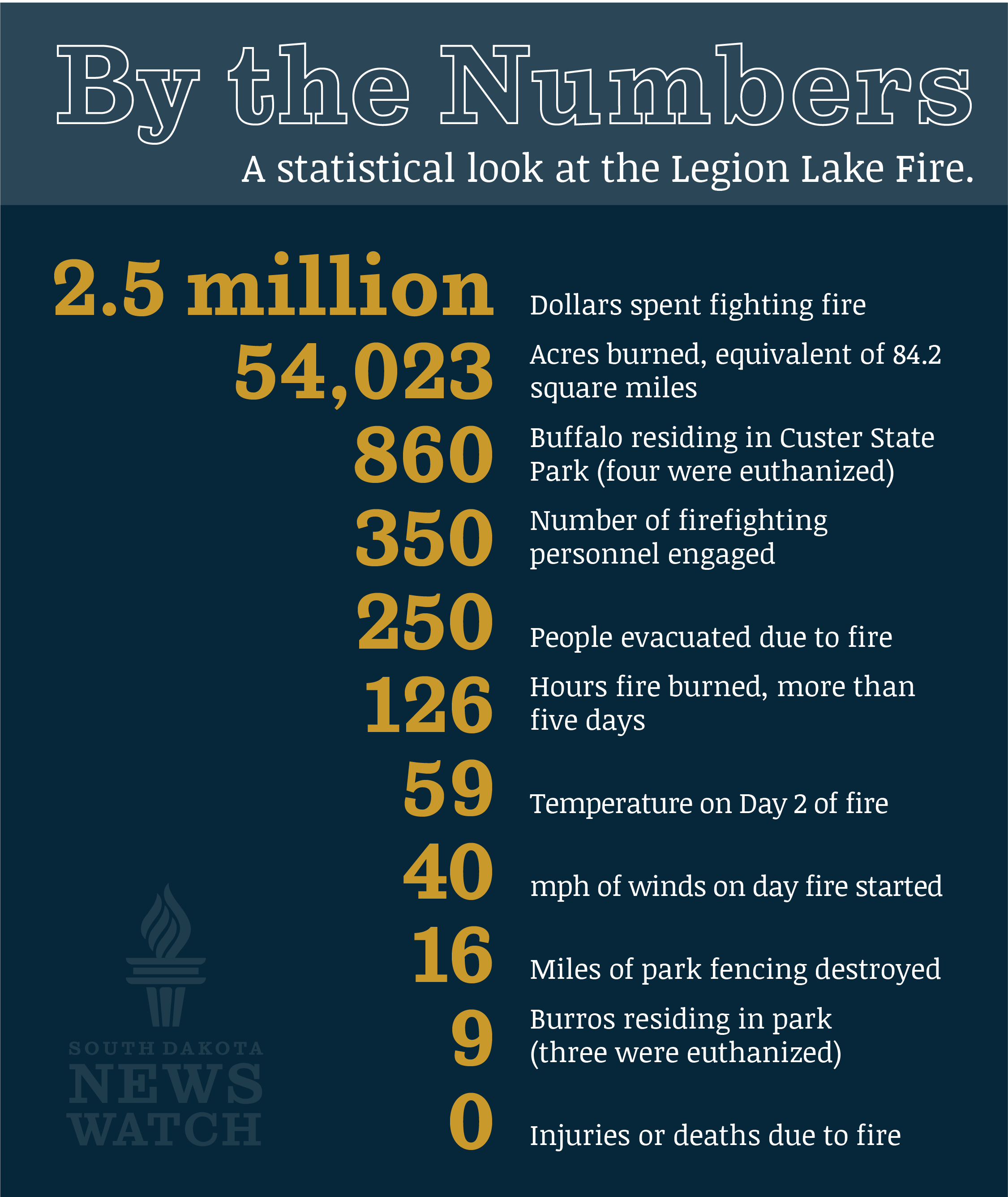

Fire officials were forced to wonder: After all the hard work, the mobilization of 350 people and dozens of pieces of equipment to fight the raging Legion Lake Fire fire, had they lost the battle in the end? Could it be that their combined decades of firefighting experience weren’t enough to stop a fire that was the size of a pickup truck when discovered?

The answers could not be known as sunset fell on that Tuesday.

In this first behind-the-scenes account of the fire, officials walk through those precarious hours as they worked to subdue the erratic flames of what would become the third largest fire in Black Hills history.

They could not have known at the time that the fire would scorch more land area than the city of Sioux Falls, and that protecting the sprawling 71,000-acre park expanse of grassland, forest and historic structures would come at a cost, including the loss of some of the park’s iconic wildlife. The rare winter firefight would reshape the enduring Black Hills landmark.

Facing such hectic uncertainty on that December night, the incident commanders and firefighters were certain of just one thing: They weren’t going down without a fight.

Line goes down, fire comes up

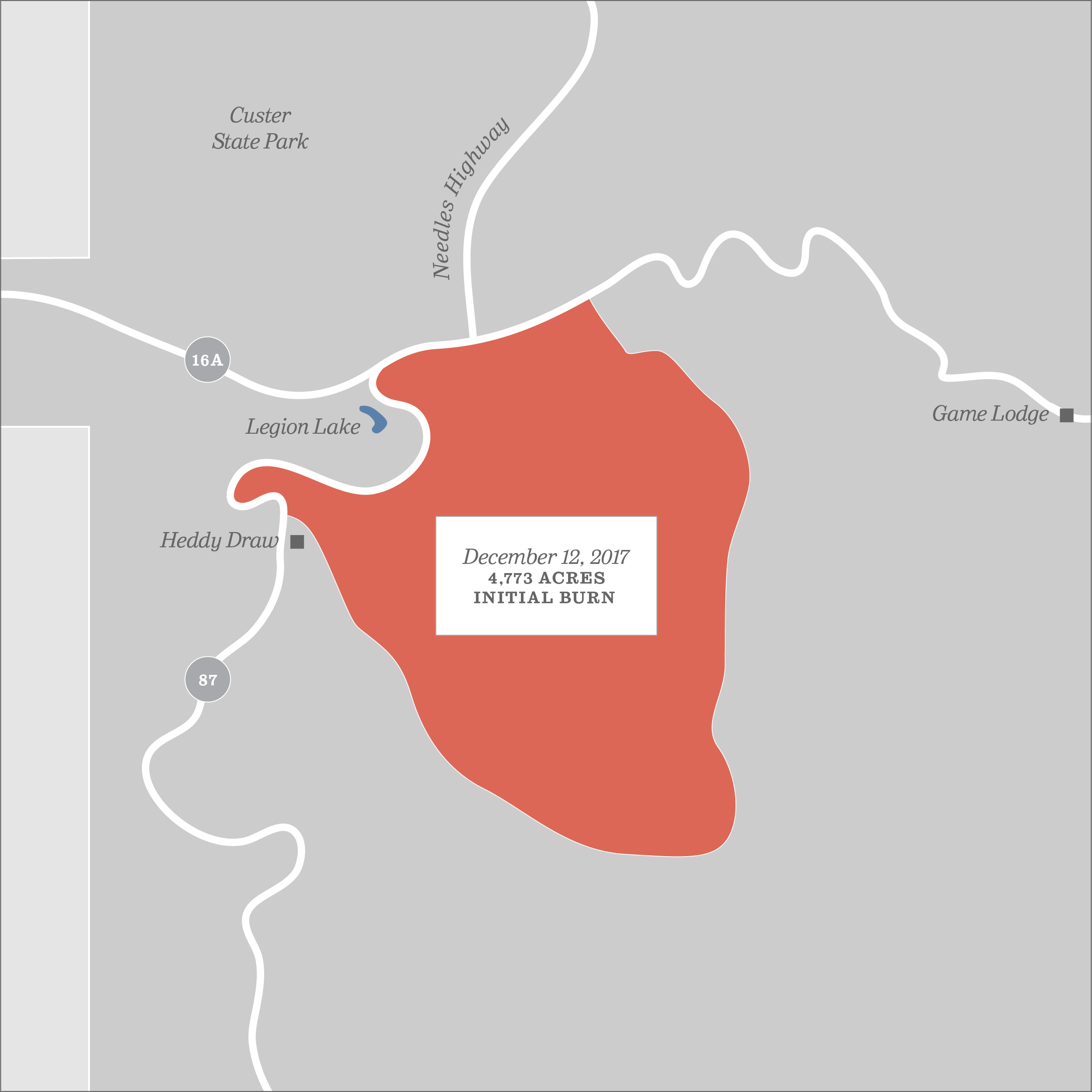

The fire that would come to be known as the Legion Lake Fire began when high winds toppled a tree that cut through a live power line just after 7:40 a.m. on Monday, Dec. 11.

The first people to spot the blaze were park employees Tom Miklos and Ron Tietsort. Miklos had just returned a bag of borrowed goose decoys to Tietsort at his cabin at the intersection of Needles Highway and U.S. 16A when they saw the fire burning across the street. They immediately called the home of Jay Wickham, the park fire management officer, who lives in a park cabin a few miles away on 16A.

“I was walking my dogs in the woods across the street from my house, and my daughter came running out of the house in her robe shouting, ‘Daddy, Daddy, there’s a fire!’” Wickham recalled.

His wife appeared, holding his fire-resistant Nomex pants. “I grabbed my pants and went to the fire,” Wickham said.

A few park rangers were there on the scene — located atop a ridge 50 yards south of the Needles/16A intersection — and already, just 10 minutes after it ignited, the fire had spread to about 15 acres.

Wickham is no stranger to forest fires and how they evolve. A native of Kimball, Neb., the 46-year old father of four has been with the South Dakota Wildland Fire Division since 1998. He has lived and worked in Custer State Park the past 11 years.

Wickham’s initial assessment of the fire indicated it was a fairly fast-moving surface fire, a typically containable blaze that had not yet reached into the treetop canopy. But the fire was spreading quickly, and it soon became clear that it would be folly to attempt a “direct” approach to fighting the fire, in which people on the ground use water and equipment to extinguish a blaze directly in front of them.

A group of firefighters arrived on the scene. Some of them had battled a forest fire near the Crazy Horse Memorial north of Custer that morning.

Wickham quickly drew up his “indirect” firefighting plan and drew boundaries for the first “box” for the fire. An indirect approach means getting ahead of the fire and removing fuel and building fire lines to block its growth.

The “box” is a term firefighters use to describe roads or geographical features that give the fire a set of boundaries. They then set controlled fires, dig trenches and begin removing fuel so the fire can burn itself out within the box.

Wickham settled on a box framed by three paved roadways, including Badger Clark Road, U.S. 16A and a driveway to some cabins east of Legion Lake. That would have contained the fire to about 50 acres, “and I thought we could hold it to that,” Wickham said.

But soon the fire reached some machine piles, giant mashes of sticks and branches piled up after a logging operation. Machine piles, some as large as a trailer house, are left in the woods until significant snow falls, allowing fire officials to set them ablaze and safely reduce them to ash.

The piles in the path of the fire were about two years old and had become dry and brittle due to western South Dakota’s extended drought. They caught fire and became an inferno.

“We had 100-foot flame lengths once those ignited,” Wickham said. “When you get flames like that, it quickly throws embers a distance downwind, and that’s exactly what happened.”

Just 30 minutes after Wickham arrived, the fire had blown past Badger Clark Road and was now off and running. Already, his initial plan had failed.

Four or five fire engines had since arrived, but with the fire moving so quickly, there was little that a few water hoses could do to stop the fire, Wickham said. “We had to readjust, and then we had to draw our next box.”

Now faced with an out-of-control wildfire, Wickham decided that he needed help. At 10:18 a.m., he got on the radio and called for a Type III fire team, a move that upgraded the response and could bring in as many as 50 on-call fire personnel and much more equipment to the fight. The call also triggered the need for a more experienced incident commander who could oversee the attack on a larger, more dangerous fire.

“It was going to be big”

With his steel-blue eyes, a quiet but confident countenance and a splash of grey on his sideburns and beard, Rob Powell of Rapid City feels immediately like a guy you can trust.

Powell, 58, retired in 2016 as a battalion chief after 29 years with the Rapid City Fire Department. He gained valuable expertise in his side job as an on-call commander of several wildfires in the Black Hills and beyond, a call he still responds to as a commander with the Rocky Mountain Blue Team fire force.

After receiving the report from Wickham and a short conversation with his boss, Wildland Fire Division Chief Jay Esperance, Powell drove to the park. From his home near Johnson Siding, west of Rapid City, Powell got his first sense of the ferocity of the fire when he could clearly see a smoke column rising above the park some 30 miles to the south.

When he arrived at the incident command post a half hour later, he suddenly was in charge of a complex effort to protect human life and property in South Dakota’s most iconic park. Often called the crown jewel of the state park system, the park attracts nearly 2 million visitors a year.

Powell was briefed about the fire during an intense ride with Wickham, who had already decided that homes and cabins at the former STAR Academy and other locations in the fire’s projected path should be evacuated. Fire crews had also been dispatched throughout the fire zone.

But as Wickham and Powell pulled onto a road that runs above Heddy Draw, a deep pine-encrusted canyon a couple of miles from the fire’s origin, Powell grew more concerned.

“I knew it was going to get big,” he said. “There was just no good place to cut it off.”

“I knew it was going to get big,” Rob Powell said. “There was just no good place to cut it off.”

December is not a good or common month to fight a wildfire. Most paid wildland firefighters who respond from outside the region, some known as the Hot Shots, were off for the season; others were in California battling devastating fires there. Volunteer firefighters also tend to see winter as their slow season and are not as prepared as they might be in the summer.

Powell decided he had to upgrade the fire response to Type II. That move would add a specialized team of firefighters from five states and far more equipment including aircraft. It also would significantly raise the cost of fighting the fire.

Powell knew the fire was taking advantage of wind speeds up to 40 mph, low humidity and plentiful fuels, and was growing rapidly. “The whole time, that fire is cranking, and we had no idea where the head was at or where it was going,” he said. “It was just ripping over the top of ridges and into canyons, and we couldn’t get in there because it just wasn’t safe.”

In addition to the commitment to protecting human life, the fire team turned its focus to what is known as “point protection,” the securing of valuable structures within the park. An overriding concern was the protection of the State Game Lodge, a grand, historic hotel and restaurant first built in 1922 that has hosted presidents and other dignitaries. Esperance had been in contact with Gov. Dennis Daugaard’s office and protection of the game lodge was high on the governor’s list of goals for the fire team.

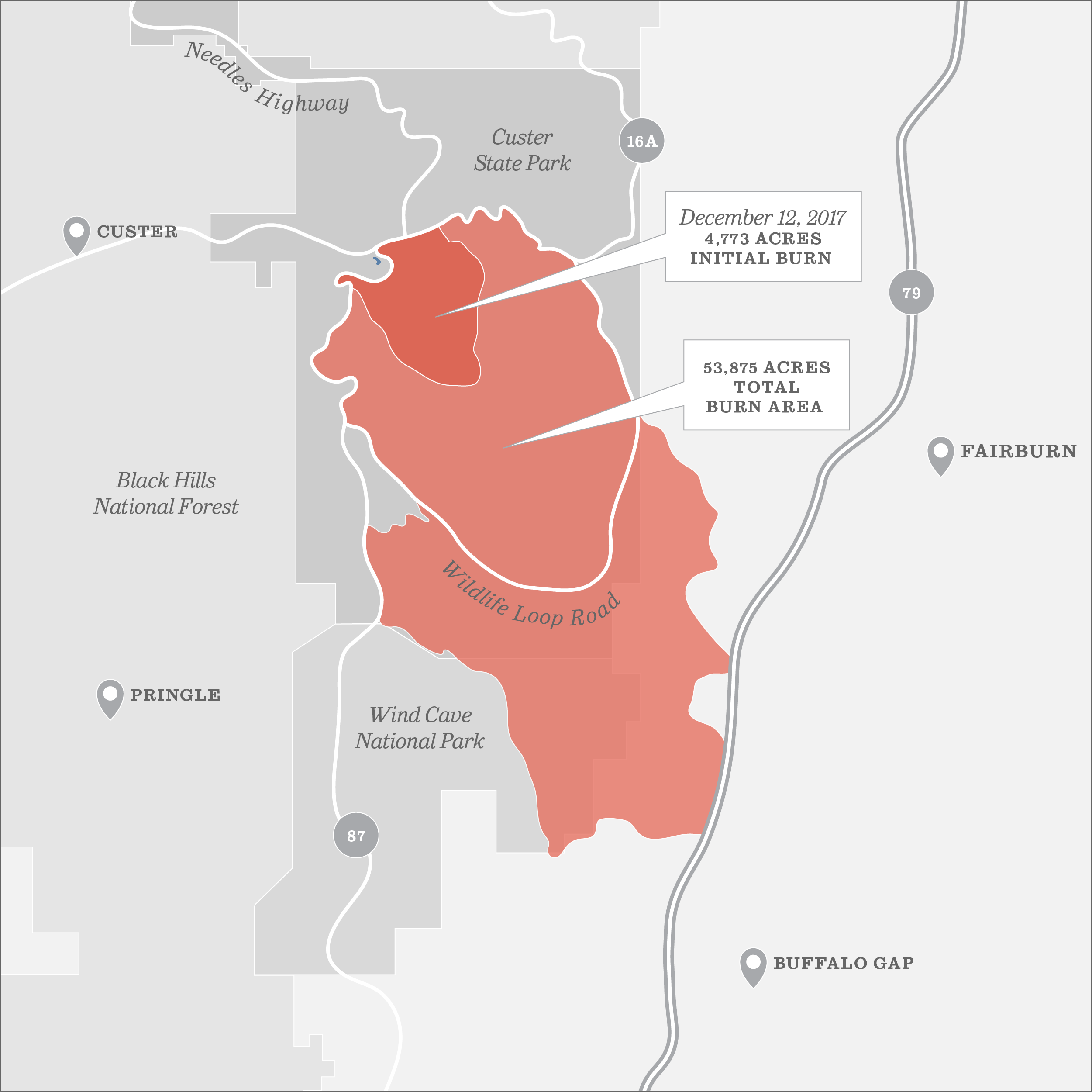

Powell, meanwhile, created a new box for the fire that used a series of internal park roads as boundaries. He now hoped to contain the fire to roughly 15,000 acres. The southern line of the box was extended to the Wildlife Loop Road, an 18-mile road that separates the wooded interior of the park from the mostly flat prairie lands to the south.

“That’s a big chunk of the park, so I wanted to make sure the park superintendent knew that, and all the way up to the governor,” he said. “Everybody was on board.”

As nightfall came, Powell and others on the command team prepared to bed down and let overnight crews monitor the blaze. A handful of fire engines stayed active to beat back the fire overnight.

Officials with the private management company that runs park facilities, the Custer State Park Resort Co., opened the game lodge and other nearby cabins to firefighters and officials who couldn’t leave the scene. The company also provided hundreds of meals and other necessities to firefighters.

Powell said he made his way to bed at the Creekside Lodge sometime close to midnight, confident that the fire would slow its roll during the cool overnight hours.

“Normally the wind goes down and humidity comes up, and they lay down at night,” he said. “But this one didn’t.”

“With 60 mph wind gusts, temperatures in the high 50s and low moisture, it just set up for like a bomb going off, which is actually what it did.” ~ Rob Powell

‘Like a bomb going off’

When he arrived back at the command post in the state park maintenance shop around 5 a.m. on Tuesday, Dec. 12, Powell hosted a morning briefing that brought more bad news. The overnight commander told Powell the fire never stopped its south and eastward march. “It burned hard all night, a few thousand acres,” Powell said.

On top of that, the weather forecast was not favorable. Powell learned that more high winds were in store, likely to blow in around 3 a.m. on Wednesday.

Crews began to burn areas along state Highway 87, near the western boundary of the park, to prevent the fire from shifting to the west, threatening private homes and ranches between the park and the city of Custer. Officials were confident that line would hold, and began to shift their focus to the fire’s projected southeastern path.

To prepare for the worst, fire crews were sent to the park’s main buildings at the east entrance. There they began using bulldozers to clear fuel from around the structures, cutting down trees that might burn and allow embers to jump. Using drip torches, they burned fuel away from the buildings and back toward the blaze. The fire had moved almost to the back doors of the Game Lodge, the Creekside Lodge, other park administration buildings — and to Wickham’s home.

Wickham’s wife and children already had evacuated. He was one of several park employees fighting to protect their own homes and belongings.

Meanwhile, fire crews were sent to the outer edges of the box, where the line was holding for the most part.

But on Tuesday afternoon, Powell and his team got a big shock. The whipping winds that were scheduled to come overnight on Tuesday arrived instead around 4 p.m, only 50 minutes before nightfall. Suddenly, the fire took on a whole new urgency and sense of rage, and it appeared as though the firefight would have to take place in the dark.

“The wind showed up at 4 o’clock on Tuesday afternoon, and when I say it showed up, it showed up with something like 60 mph wind gusts,” Powell said. “With 60 mph wind gusts,

temperatures in the high 50s and low moisture, it just set up for like a bomb going off, which is actually what it did.”

At that moment, Powell and the others knew they could be in for one of the longest and most dangerous nights of their firefighting careers.

A massive team effort

Powell remembers being in a truck and watching the flames whip across the prairie near Wildlife Loop Road, consuming hundreds of acres as it leapt. “There were sheets of flame coming across prairie dog towns,” he said.

With the winds high and night coming, he knew it was time to take drastic action. Powell called the South Dakota Highway Patrol and asked the agency to shut down Highway 79, the main four-lane, north-south highway in western South Dakota.

Firefighters on his team joined scores of volunteers from townships and firefighters from nearby municipalities – as many as 350 people – scrambling to save people and buildings in the fire’s path.

Roughly 200 homes were evacuated. Then, at about 7 p.m. on Tuesday, the fire jumped the Wildlife Loop Road, making its way out of the park and bringing more homes and ranches into its path.

“The people there, they’re looking at a wall of flame,” Powell said. “They knew it was time to get their horses and dogs and cats and cattle in a safe place where they can survive, and then get out.”

In some cases, fire crews went from property to property, burning off fuel around structures before laying down water to prevent the oncoming fire from consuming homes and ranches.

The additional equipment brought in to fight the fire from above — two tanker planes from California and a helicopter from Colorado — were rendered ineffective. One tanker had mechanical problems and couldn’t fly, and it was too windy for the other aircraft to risk a flight.

Powell was constantly fearful that lives could be lost. He said embers were flying over cars and trucks, and he reiterated over the radio several times that firefighters should not chase the flames or the head of the fire and focus instead on their safety. He worried that someone might get struck by a falling tree, or other debris.

“There were several, several close calls that night,” he said. “But people just kept working.”

The fire raged with the high winds after dark, and Powell said he was stunned at its ferocity.

“It made a 40,000-acre run … at night … in December … in timber … in a period of about five hours,” Powell said. “That’s an extreme fire.”

Finally, a break

Just as things seemed to spin out of control and the threat to lives, homes and other structures appeared to spike, the weather finally cooperated and the hard work of the fire crews began to pay off. Late on Tuesday and into Wednesday morning, the winds subsided, the humidity increased and the fire’s progress slowed.

During the day on Wednesday, the helicopter finally took flight and gave Powell and his team a good look at where the fire was burning and where it was headed. That allowed them to use the tanker planes, now functional, to make several dumps of retardant over lands within Wind Cave National Park to block the fire’s southern path.

Back-fires were lit to prevent the fire from spreading farther on private land. Fire crews stayed vigilant and began to fight the fire in a more direct way, especially on the private lands outside the park, finally bringing it into partial containment. “On Wednesday afternoon, we started to turn the corner,” Powell said.

On Thursday, the humidity rose even more and some snow fell on the north side of the fire. Crews continued to move through the fire zone, turning over smoldering snags or stumps and putting them out.

The “mopping up” process continued for the next two days, and on Saturday, Dec. 16, around 1 p.m., officials declared the fire 100 percent contained. Some crew members and support staff members began to return home.

‘People all over the country were watching’

On a morning in mid-January, Powell, Wickham and park Fire Forester Rochelle Plocek gathered to discuss the fire, the battle against it, and what they took away from the experience.

Powell was most thankful that no one died and that no major structures were lost. He was also impressed with how the entire fire team responded during that dangerous Tuesday evening firefight.

“It was a huge fire in the winter in the Black Hills that everybody came together with the few resources we had, and it all came together,” he said. “I think angels watch over us all the time, and I think they were watching over us for sure on that Tuesday night.”

Plocek said she was impressed with how much the park’s private facilities management company aided the firefighters and how many non-fire employees within Custer State Park stepped in to help. Some office workers even went out to the Wildlife Loop Road and helped repair fences around the buffalo corrals to keep the bison herd intact, she said.

She, like the others, also felt a constant emotional burden, feeling that in some ways the world was watching what happened with the fire, monitoring the potential destruction of a world-renowned tourist destination.

“The buffalo herd, the donkeys, the historic buildings — a lot of that stuff is very important to a whole lot of people,” she said. “This was a big deal, a very politically charged event that people from all over the country were watching.”

Wickham also reflected on how personal the fight was to Black Hills residents.

“People who live in the Black Hills, they take a lot of pride in Custer State Park,” he said. “It’s a lot of people’s backyards, and that makes it different.”