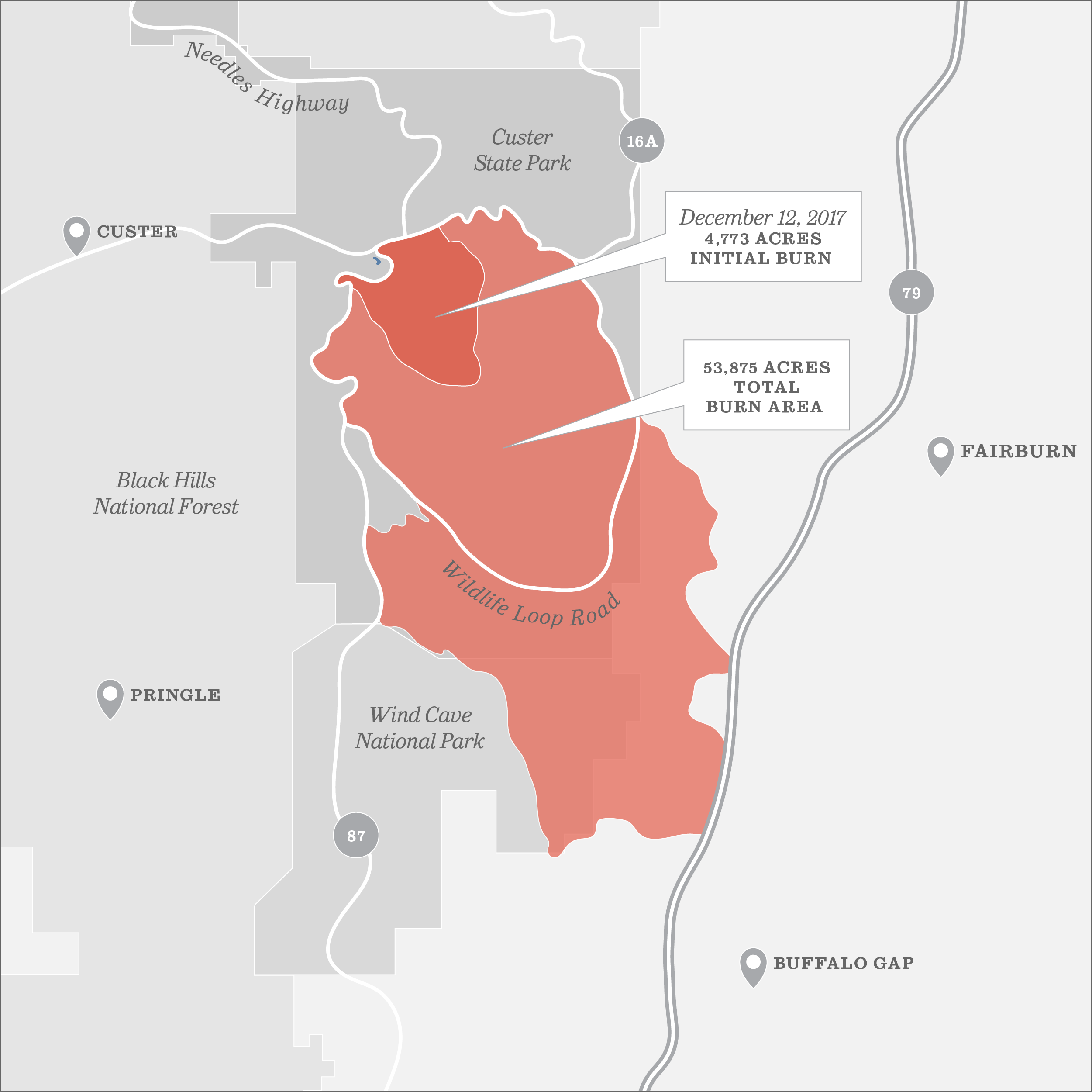

Historic Custer State Park bears visible scars from the December fire that unleashed 100-foot high flames across 54,000 acres.

Dozens of towering ponderosa pines in the park’s central wooded region are blackened to the crown. Huge swaths of once honey-colored open prairie lands are now crunchy and the color of overdone toast. And though the wildlife population fared well overall — including the 860 bison that call the park home — three of the park’s beloved begging burros had to be euthanized after the blaze. A few more remain in peril due to burn injuries. The smell of a campfire that burned too long still wafts in the dry western South Dakota air.

Yet, if there’s any place that can recover quickly from such a furious fire, it is this park. That is the optimistic and science and history-supported prediction made by Rochelle Plocek, a fire forester for the state Game, Fish & Parks Department who works in the park.

This park is shaped and even strengthened by fires that have raged among its statuesque pine ridges and valleys, granite outcroppings and fertile prairies for centuries, she said.

Given that history, Plocek is confident that the black ashen blanket laid upon much of South Dakota’s most popular state park by the Legion Lake Fire of 2017 will quickly be washed away by spring moisture and blossom into a verdant landscape once winter passes.

“Once the spring rains come and that green grass grows back, it’s going to come back so strong and so well that visitors are going to say, ‘Wow, this is really green and pretty,’” Plocek said.

Her colleague, park Fire Management Officer Jay Wickham, is even more certain that park visitors won’t be put off by the damage caused by the Legion Lake Fire, the third largest in known Black Hills history. The Jasper Fire burned 83,500 acres west of Custer in 2000 and the Oil Creek Fire scorched 63,000 acres in eastern Wyoming in 2012. In fact, Wickham thinks most spring and summer visitors may not even notice that a fire took place.

“If you’re a regular visitor from Rapid City or someone who comes down for Sunday drives, you’ll notice some dead trees in the park,” Wickham said. “But for the average visitor from Pennsylvania or Ohio or Minnesota, it won’t be any different than if they came last year.”

Popular visitor sites were spared

If a recent tour of the fire-ravaged areas are any indication — a visit just six weeks after the blaze — the park employees’ confidence appears justified.

For starters, the fire began at a spot just south of where Needles Highway terminates at U.S. 16A and it moved quickly with the winds to the southeast. That left significant areas of the park undamaged, including popular visitor sites such as the Stockade Lake area to the west, the northern fifth of the park that includes Center Lake and the Black Hills Playhouse on the north, and the famed Needles Highway route that runs through the cathedral spires, narrow vehicle tunnels and picturesque Sylvan Lake area to the far northwest.

The area directly around Legion Lake Lodge was mostly spared, but the fire was most damaging where winds carried it through the Badger Hole, Heddy Draw, Blue Bell and French Creek areas and down to the southern borders of the park. Many trees were almost completely blackened in the central, more wooded areas of the park where the fire burned hottest and longest. Wooden fence posts in those areas were either scarred or incinerated, in some cases leaving loose wire fencing lying useless on the ground. Replacing the fencing is a long-term recovery task.

In the southern third of the park, huge swaths of native grasses that usually create a sea of sandy colored prairie lands along the park’s popular Wildlife Loop Road now lie blackened and seemingly lifeless.

Ponderosa pine trees throughout the fire area, including along the wildlife loop, are scorched and could die in the coming months.

Some woodland areas that were damaged by fire will be heavily logged or completely clear-cut prior to summer, so experienced visitors may notice that a handful of once woodsy regions have been thinned or leveled. That process not only removes damaged trees and fuel for potential fires, but opens the area to new growth, Plocek said.

Arborists estimate that if a ponderosa pine — the dominant tree in Custer State Park— retains 20 to 30 percent of its green branches it can survive and thrive after a fire. The ponderosa is a fire-adapted tree that is resistant to flames due to its thick bark, strong root system and the shedding of lower limbs as it ages.

While some trees in the hardest hit areas of the park are black to the crown, many of the trees that were singed in the December fire show damaged brown bows only a few feet up their trunks. Those trees were spared because for the most part, the Legion Lake Fire burned at ground level and did not take hold in the tree canopy.

Beyond that, the tendency of the fire to burn quickly across the dry, fuel-filled forest floor left the dormant roots of many wildflowers and native grasses protected from the heat and flames, Plocek said. She and others with knowledge of the park say those areas will regrow quickly with native grasses such as western wheatgrass, prairie coneflower and bluestem once winter snows melt and spring rains arrive amid warmer weather and longer sunny days.

The hillside where thousands of patrons of the annual buffalo roundup watch cowboys wrangle the herd is completely charred but should be reborn with prairie grasses by the next event this fall.

The historic State Game Lodge where Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Dwight Eisenhower have stayed, as well as the lodges at Blue Bell, Legion Lake, Sylvan Lake and Creekside were undamaged. Guests at any camp cabin will be able to see how close the fire came by looking at the charred areas right up to the building foundations. The park’s $6 million Visitor Center, which opened in 2016, also survived unscathed.

Burros ‘took the brunt of the fire’

The outlook is equally positive for the park’s cherished wildlife, which includes its prized buffalo herd as well as elk, mountain goats, pronghorn antelope, deer and coyotes, all species that have known fire and simply fled to avoid the flames and smoke in order to survive, Plocek said. Park officials did find a handful of big-game animals that succumbed to the fire, including a bull elk found dead off a northern section of Lame Johnny Road.

Some of the bison suffered burn injuries, and many others endured smoke and ash inhalation, Plocek said. Four buffalo were humanely euthanized after the fire, she said. The park lost most of its buffalo grazing lands, but herd managers have made do with donations of hay through a national non-profit (farmrescue.org) and by way of financial contributions that have poured in since word of the fire reached a national audience. About 800 of the park’s 860 buffalo are being held in the corrals inside the Wildlife Loop Road, where it is easier to monitor their health and provide them with the tons of food they need each day. Once the park greens up and all 16 miles of destroyed fencing is repaired or replaced, the buffalo will be released onto their normal grazing grounds.

Avian residents of the park, such as the mountain bluebird, golden eagle, western tanager and sharp-tailed grouse simply flew to safety. The camera-friendly prairie dogs who live in established “towns” on the flats survived en masse by fleeing into their deep burrows where it was cool and they had food stored, Plocek said.

The hardest-hit animals in the park were among its most famous: the non-native burros that often beg for carrots and other snacks from motorists who find the mules milling about at several pullouts along the Wildlife Loop Road.

Plocek said the park sold off a dozen or so of the burros in a resource management move in November, leaving nine mules in the park at the time of the fire. As a species unaccustomed to fire, the burros fled to places unknown during the fire, and almost all suffered burn injuries, some of which were severe, she said.

“They (the burros) took the brunt of the fire,” Rochelle Plocek said. “We do know the fire moved through their area very quickly and very hotly, and they did not have the instincts to move out of the way.”

Three of the surviving burros were euthanized and buried in early January, she said, because their injuries were not healing. To illustrate the popularity of the so-called “begging burros,” Wickham noted that a park Facebook post about the burros’ deaths drew 250,000 views, compared to about 50,000 views for a typical park update on the fire.

On a mid-January drive along the Wildlife Loop Road, it was evident that the daily routine for wildlife in the park had already returned to normal.

Herds of pronghorn could be seen prancing about on both charred areas and those untouched by the flames. A few bison that are not corralled with the main herd appeared as they always do — unflinching but perhaps mildly perturbed by guests pulling over to gawk at them through car windows. A pair of sharp-tailed grouse fluttered overhead and a small group of mule deer were ambivalent to a visitor nearby as they grazed on surviving grasses near a small spring-fed pond.

Park officials have said they expect the 2018 tourism year to be as strong as in 2017, when 1.94 million people visited the park and a record 21,000 attended the 52nd annual buffalo roundup.

Park regular Larry Chilstrom of Rapid City, who was on a legal coyote hunt in the park on a warm winter day in January, said it is unlikely the fire will keep people away.

Chilstrom predicted that the park’s many charms will override any worries of potential visitors that the park changed for the worse.

“The damage is widespread, and there’s a lot of tree areas that are burned and those won’t come back,” Chilstrom said. “But it’s still a big attraction for South Dakota. As long as the buffalo and the burros are here, people will keep on coming.”