Part 1 of a 3-part series

Attorney Jeffrey Montpetit knew that obtaining a video of a South Dakota Highway Patrol trooper's actions after a 2015 DUI arrest in Clay County would be critical to his client's civil case alleging excessive use of force by the officer.

As a lawyer, Montpetit was able to view the video that showed Trooper Cody Jansen restrain Troy Rokusek in the Clay County Jail by pulling both his arms behind his back in a disabling move called a "double chicken wing." According to court documents, Jansen then threw Rokusek face first into the ground, breaking off two of his teeth.

In his official report, Trooper Jansen – who was named the 2017 South Dakota State Trooper of the Year – said Rokusek resisted arrest, which would have justified the violent takedown maneuver. But after Rokusek sued Jansen, a judge ruled that the video did not corroborate Jansen's claims. In September 2018, the state of South Dakota made a $100,000 payment to settle Rokusek's civil case.

The Rokusek lawsuit wasn't the only time Montpetit has tried to obtain videos to support civil cases filed against authorities in South Dakota. And in each instance, it was challenging to get videos that show what really happened during interactions between law enforcement and the public.

"A lot of times in South Dakota, it's just damn near impossible to get any of these videos because of the way that their statutes are written," said Montpetit, who is based in Minneapolis but represents plaintiffs across the Great Plains. "In a lot of cases, the circuit court judges in South Dakota will write into their orders that the files should remain locked and sealed."

While it can be difficult for lawyers to obtain copies of videos from police dashboard, body or facility cameras, it is nearly impossible for the public or media to see video evidence in South Dakota.

State laws give police wide discretion

State statutes in South Dakota provide law enforcement agencies and prosecutors with near-complete discretion on whether to release a wide variety of police records – including videos – for public review.

The state's open-records law is commonly used by state, county and local law enforcement agencies to deny the release of information and thereby avoid public scrutiny of their actions and interactions with the public.

"A lot of times in South Dakota, it's just damn near impossible to get any of these videos because of the way that their statutes are written."

-- Attorney Jeffrey Montpetit

David Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota NewsMedia Association, said South Dakota public records laws are among the weakest in the nation, giving law enforcement agencies in particular the right to deny public or media access to records in almost all cases.

“It’s a very weak law in regard to law enforcement,” Bordewyk said. “It’s extremely broad and it allows law enforcement to legally keep just about anything and everything from the public.”

While neighboring states allow public access to common police records such as incident reports and probable cause affidavits, and police videos in some cases, South Dakota laws give law enforcement agencies wide discretion on what is released or not.

Almost all police agencies in South Dakota use cameras in cars and on uniforms to record activities in the field.

“They say, ‘Well, the law allows us to keep these videos confidential, so we can and we will,'” Bordewyk said. “That’s opposed to saying, ‘We do have discretion but we want to lean toward full accountability and transparency, and by golly we’re going to show the public what this investigation has concluded.' But that just doesn’t happen in South Dakota.”

South Dakota is increasingly an outlier when it comes to lack of public access to police videos, even as public pressure to release them has increased after numerous high-profile national cases in which videos showed officers taking questionable or illegal actions.

“It’s a very weak law in regard to law enforcement. It’s extremely broad and it allows law enforcement to legally keep just about anything and everything from the public.”

-- David Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota NewsMedia Association

Some states, like Colorado, have passed laws to make all police videos a public record, while other states allow release once privacy and other prosecutorial concerns are met. The federal government also routinely releases law enforcement videos upon request if privacy concerns can be alleviated.

Open-government advocates say releasing videos to the public and media improves transparency, increases accountability of officers and can ultimately lead to increased public trust in law enforcement.

South Dakota is one of 13 states that has not passed some form of legislation to regulate the maintenance and public release of policy body camera videos, according to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

AG: Video releases could impede justice

The lack of public disclosure comes despite the fact that taxpayer dollars, either in local taxes or from federal grants, are used to pay for law enforcement cameras and the videos they generate. Many agencies pay tens of thousands of dollars a year to generate, process and store videos from dashboard and body cameras.

South Dakota Attorney General Marty Jackley said he supports government openness but added the release of law enforcement records could have negative effects on both police agencies and the public.

In an interview with News Watch, Jackley said that as the state's top law enforcement officer he understands that there is a desire for government openness but also a duty by law enforcement to protect the rights of both victims and defendants while upholding the fairness of the legal system.

"I've tried to be as transparent as I can without affecting public safety, privacy and the sanctity of the courtroom," he said.

Jackley said he would not support release of law enforcement records, including videos, that could prevent prosecutors from making a case or inhibit a defendant's right to a fair trial. The improper release of records or video could make it also harder for someone to file a civil case against a law enforcement officer, he said.

"I pride myself in never losing a case because of an inappropriate disclosure of evidence," Jackley said.

News Watch requests for videos denied

South Dakota News Watch tested the state's open records law by filing formal public records requests in an effort to obtain videos from eight law enforcement agencies.

To determine which records to request, News Watch reviewed numerous state investigative reports regarding officer-involved shootings to locate cases in which dashboard or body camera video evidence was specifically mentioned as part of the material reviewed by investigators.

In early November, News Watch made requests to the state Department of Public Safety, police departments in Sioux Falls, Rapid City, Huron and Yankton, and sheriff's offices in Minnehaha, Pennington and Corson counties. All eight police-involved shootings – ranging from 2016 to 2025 – were declared justified by state investigators.

None of the agencies agreed to provide the video evidence to News Watch, including from a closed 2016 case in Pennington County in which the defendant, Abraham Fryer of Sturgis, was shot and killed by a deputy.

In denying News Watch's request for access to videos, most of the agencies cited state statute SDCL 1-27-1.5(5), which declares that “records developed or received by law enforcement agencies and other public bodies charged with duties of investigation” are not open records.

Not a single agency asked questions about the requests by News Watch or tried to determine if there was a way to provide access without harming a criminal case or violating someone's privacy.

Local agencies have custody over videos

In a letter denying the News Watch request, management analyst Arin Diedrich of the Department of Public Safety provided a basic explanation for the denial that was similar to those given by other agencies.

"Your request for dash-cam footage is denied pursuant to SDCL 1-27-1.5(5), which provides that records developed or received by law enforcement agencies and other public bodies charged with duties of investigation or examination of persons are not subject to disclosure," Diedrich wrote.

Jackley pointed out that the police agency that recorded the video – and not the attorney general's office – holds the custodial right on whether to publicly release material. A member of the public or media could seek a court order to obtain access to evidence in a criminal or civil case, including videos, he said.

Jackley said there are three avenues for videos in high-profile cases to become public – either in a criminal or civil trial or through an open examination by the state Law Enforcement Training Commission, which reviews some police actions in South Dakota.

"If it's a video that has a level of controversy, it's either going to be disclosed or likely disclosed in a criminal trial," he said.

However, in numerous internet searches related to police videos in South Dakota, News Watch found only a few instances where footage was released and almost never in a case where the actions of law enforcement officers were in question.

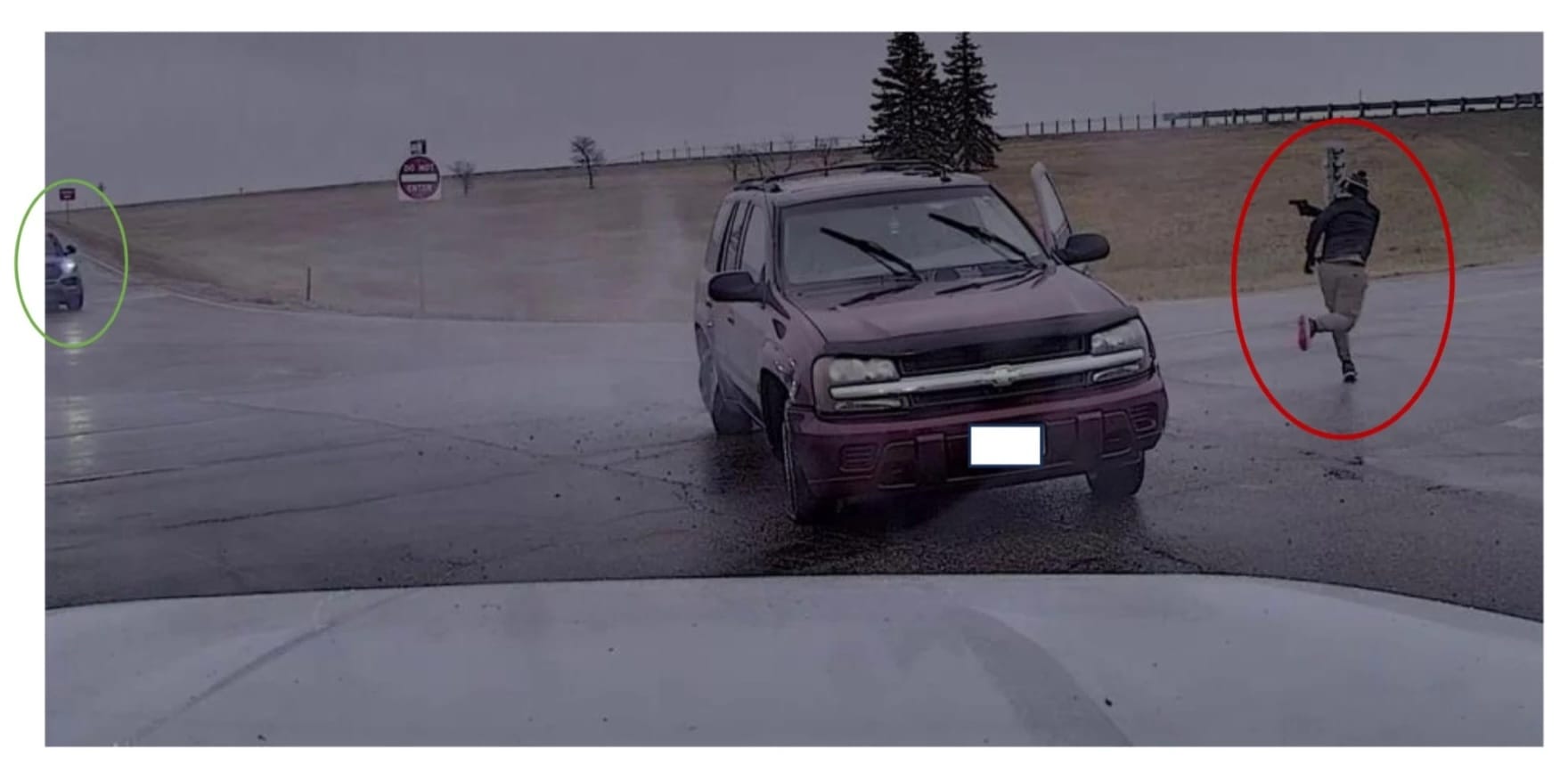

Editor's Note (caption for main photo): This still image was released by the Sioux Falls (S.D.) Police Department from a video showing 24-year-old Deondre Gene Black Hawk holding a gun during a foot chase with an officer, who shot and wounded Black Hawk. (Photo: Courtesy South Department of Public Safety)

Parts 2 and 3:

Wednesday, Dec. 17: The surprising instances when police videos have been released in South Dakota, and a deeper look at how camera programs function

Friday, Dec. 19: A 2020 legislative effort to regulate body camera videos never made it to a vote, maintaining South Dakota's national reputation for law enforcement secrecy

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact content director Bart Pfankuch at bart.pfankuch@sdnewswatch.org.