MISSION, S.D. – A cracked and peeling wooden sign signals the entrance to St. Thomas Catholic Cemetery in Mission, where Rose Cordier-Beauvais paid her respects.

The November sky was spotless for a visit to the gravesite of her grandson, Honor, who died Dec. 15, 2022, at age 12 during winter snowstorms that ravaged the Rosebud Indian Reservation in south-central South Dakota.

Honor Beauvais was one of six people who died during the 2022 holiday blizzards, which shut down roads and stranded residents, some of whom ran out of propane to heat their homes. Gov. Kristi Noem declared an emergency on Dec. 22 and activated the state’s National Guard to haul firewood and remove snow.

The death of Honor, a sixth grader with asthma living with his aunt and uncle on the reservation, has come to encapsulate the challenges and shortcomings of the disaster response, whether from state, federal and tribal officials or the Indian Health Service.

“Nobody ever said they were sorry,” said Cordier-Beauvais, 70, who works as business manager for the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. “They were too busy trying to get their story straight.”

She recounted how Honor was taken to the IHS emergency room in Rosebud on Dec. 14 with flu symptoms and breathing difficulties. He was evaluated, given medicine and released.

He stopped breathing the next day and died, with massive snowdrifts preventing an ambulance from reaching the family’s ranch until it was too late.

Cordier-Beauvais, represented by Sioux Falls attorney Brendan Johnson of Robins Kaplan LLP, is pursuing a medical malpractice lawsuit against IHS. The lawsuit is expected to be filed in the next 60 days.

“Honor’s death was an avoidable tragedy,” Johnson told News Watch. “We will bring all necessary resources to bear to see justice is done, changes are made, and that Honor’s death was not in vain.”

Indian Health Service officials declined a request for comment through the agency’s public affairs office.

Cordier-Beauvais contends that her grandson should have been held at the hospital rather than released due to severe weather and the probability that follow-up care would be needed.

She also accused Rosebud tribal officials of inadequate disaster preparedness and a lack of emergency services the night Honor died, when her family’s pleas for help were not enough to prevent tragedy.

Robert Oliver, head of the tribe’s Emergency Preparedness Program at the time, told News Watch that such characterizations are unfair to the difficulties his crews faced.

The Rosebud reservation in Todd County, with about 9,500 residents and one of the nation's highest poverty rates, received snowfall of 2 to 3 feet, with winds gusting to more than 60 miles an hour.

“It wasn’t us,” said Oliver. “It was the storm.”

Tragedy revives health care scrutiny

The one-year anniversary of Honor’s death comes amid renewed scrutiny of IHS, which provides free health care to enrolled tribal members as part of the government’s treaty obligations to Native Americans.

Those rights were reinforced by an 8th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruling in 2021 after the Rosebud Sioux Tribe sued IHS following the temporary closure of the emergency room at the 35-bed Rosebud Hospital in 2015.

South Dakota’s congressional delegation introduced a bill last year to address staffing, accountability and patient care within the IHS system while instituting new whistleblower protections. That legislation has not advanced past committee.

For Cordier-Beauvais and her family, many of these declarations ring hollow. None will bring back her grandson, who moved from Denver to Rosebud in 2018 with a hopeful outlook that lifted the lives of those around him.

“It was an instant bond,” said Brooki Whipple, Cordier-Beauvais' daughter, who along with her husband, Gary Whipple, welcomed Honor into their home and treated him like a son.

Brooki Whipple and her sister, Frani Beauvais, joined Cordier-Beauvais at the otherwise empty cemetery in November as another winter loomed. They gathered at Honor’s gravesite, a dirt mound adorned with flowers and decorative stones colored by classmates.

There is no tombstone, but that will come, Cordier-Beauvais said. The past year has been a whirlwind of grief and renewal, including the birth of Gary and Brooki’s son, Link, whom Brooki swaddled in her arms while speaking of Honor.

The hope is that lingering pain from last year’s devastation can be softened by memories of a child who helped bring a family together in the toughest of times.

“Honor was special,” said Brooki Whipple. “We loved him from the moment we met him.”

New life on the reservation

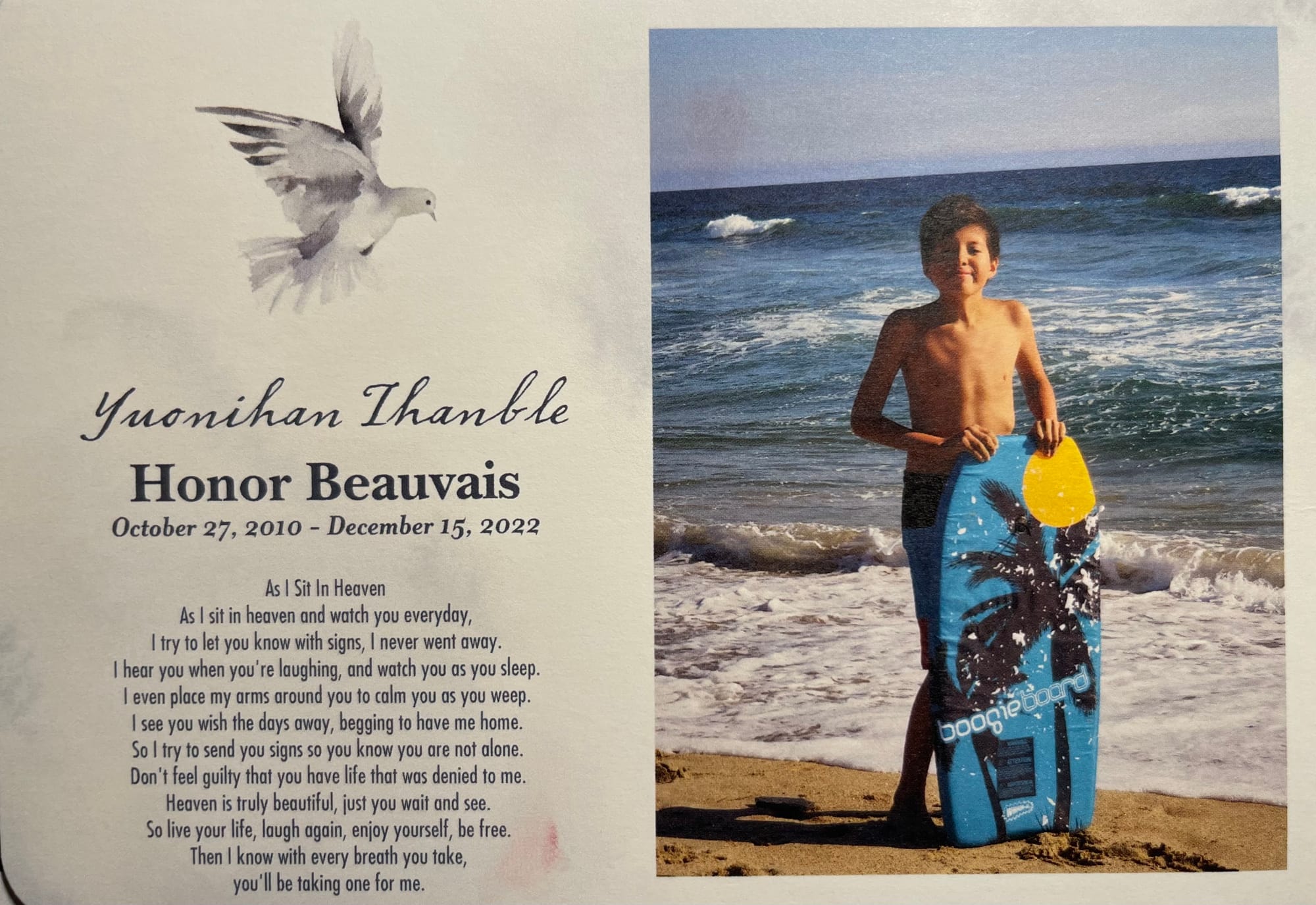

The boy was born Oct. 27, 2010, and given the Lakota name Yuonihan Ihanble. The first word means “to honor” and the second, according to translation, summons a dream “like a poetic whisper, invoking a sense of wonder and imagination.”

His name, then, was Honor Dream. Everyone called him Honor.

Concepts of home and family came in patches, tailored over time. Honor was one of four children born in Denver to Cordier-Beauvais' son, Robert Beauvais, and his common-law wife, Shennah Jordan. Their relationship unraveled as Robert attended college and worked toward law school, struggling to give the kids the stability he knew they needed.

Family bonds in Rosebud shone through. Along with his younger brother and two sisters, Honor spent summers and holidays in South Dakota with his grandmother, surrounded by cousins and aunts and uncles. Cordier-Beauvais and her clan also traveled to Denver for long weekends or birthdays.

In March 2018, she visited her son in Denver and realized that it would be best for the children to return with her to Rosebud, this time maybe for good. She noted that relatives rallying around parental roles is common in Native culture, keeping kids on a positive path.

“(Robert and Shennah) were having issues and it came out that they going to be separating,” said Cordier-Beauvais. “So we had to go get the kids because Robert couldn’t take care of them on his own. They were moving out of their apartment. Honor was 7 years old at the time.”

Forming a bond with his 'twin'

The plan was for the children to stay with their grandmother in Antelope, a tribal community near Mission. They were enrolled at Todd County Elementary School.

But Honor had his own vision.

He was close to his cousin, Arisele, or “Ari,” the daughter of Gary and Brooki Whipple. Honor and Ari both had the middle name Dream and were born two months apart. Soon family members took to calling them “the twins.” Honor spent a lot of time at the Whipple Ranch in Two Strike, a few miles north of St. Francis, where Ari attended school at Sapa Un Jesuit Academy.

Gary started out driving Honor to school in Mission and then returning to take his daughter to St. Francis before heading to work. Eventually it was decided that Honor would enroll at Sapa Un and live full-time with Gary and Brooki Whipple, who welcomed him into an active household that also included a dachshund and miniature terrier.

“Honor started bringing more and more stuff to our house,” said Gary Whipple, who works as course superintendent at Prairie Hills Square Golf Course in Mission. “Finally one day he was just like, ‘I’m living here now.’”

Honor and Ari sang “Happy Birthday” in Lakota at family celebrations and taught younger kids to do the same. He enjoyed video games such as Fortnite and later Call of Duty with Gary but made sure to play LEGO games with younger cousins, not wanting them to feel left out.

Refusing to let asthma slow him down

The spirit that endeared Honor to family members came in a fragile frame. He was smaller than most of his classmates and struggled with asthma, requiring pediatric care in Colorado before moving to South Dakota. He used an inhaler to deliver medication to his lungs.

“We would have to restrict his outdoor time when the weather got chilly, and we had an air purifier at the house,” said Gary Whipple. “He loved the dogs, but we had to keep them out of his room because of the dander.”

Honor went full speed on the basketball court, a passion he shared with Ari and Gary while playing for the Sapa Un team. The barn at the Whipple Ranch contained a basketball hoop, safe from the elements and perfect for sharpening skills.

“He would go in there and shoot around and work on his moves,” recalls Gary Whipple, who played basketball at St. Francis High School and graduated in 2007. “He saw the potential to be successful on the court and what that looked like. He wanted to be the guy, and he most definitely could have been.”

'You always knew he was there'

Honor’s understanding of home and heritage took shape at Sapa Un, a Catholic-based academy that stresses Lakota language and culture. Gary Whipple took a part-time job at the school as a physical education teacher, and Honor’s personality blossomed.

“He seemed to fit in wherever he wanted to be,” said Melissa LaPointe, a Sapa Un teacher and mother to one of Honor’s closest friends. “Even though he was quiet, he was always present. You knew he was there. He was engaged in whatever was going on.”

As his 12th birthday approached in October 2022, Honor reminded family members that since he was usually in Denver for his birthday, he had never had a proper celebration on the reservation with his friends.

He began to think about being away from his biological parents and pondering his place in the world, as sixth graders sometimes do. Some of his thoughts turned spiritual.

“He started talking to us about God and the purpose of life, watching videos about the Bible and things like that,” said Brooki Whipple, who works in the Rosebud Tribe’s communications department. “It was sort of curious and cute and funny, but one thing we noticed is that he was starting to tell us that he loved us. He gave random hugs a lot more.”

Gary and Brooki Whipple had hosted a Halloween party days earlier and kept the decorations up for a Spooktacular birthday celebration for Honor, with cousins and classmates invited. Video of the occasion shows him surrounded by singing faces as he prepares to blow out the candles.

Gary, as well as Brooki and Ari, had long since concluded that the upheaval of their household was a blessing, not a burden. Their faith in extended family never flickered.

“I taught him how to swim,” said Gary. “I taught him how to ride a bike. I taught him how to play basketball. I taught him how to fish. I was teaching him how to drive. Honor just wanted to be around. It didn't matter if we were doing something fun or not. He wanted to hang out. I remember at one point he asked if he could get a loft bed when he was 12, and I was like, ‘You’re still going to be living with me when you’re 12?’ And he was like, ‘of course.’ It was obvious to him. He didn’t want to be anywhere else.”

Hazardous trip to IHS hospital

The winter storms that ravaged South Dakota in December 2022 didn’t come without warning. But few could have predicted the impact on reservations such as Rosebud and Pine Ridge, with limited capacity for emergency response.

What started as freezing drizzle on Monday, Dec. 12, turned into heavy snowfall and driving winds the following day. Plows struggled to clear roads around Mission and St. Francis, with the National Weather Service warning of “difficult to near-impossible travel conditions.”

The weather compounded a hectic week in the Whipple household. Brooki had given birth to Link on Dec. 5, with complications requiring a trip to Sioux Falls for neonatal care.

Honor and Ari stayed with Gary’s mother, who lived nearby and could take them to school. When Gary returned on Tuesday, Dec. 13, for Ari’s last basketball game and a dinner event at Sapa Un, he sensed something was wrong with Honor.

“I could see it in him,” Gary said. “He was not as peppy as he usually was.”

Weather conditions worsened the following day, as did Honor’s health. He had a bad cough, body aches and fever, and he was finding it hard to breathe.

The Rosebud IHS posted Wednesday, Dec. 14, that it was assessing the status of hospital services for Thursday due to the storm, though the inpatient and emergency departments would remain open. “Please do not travel unless absolutely necessary,” the message said.

Gary risked tough driving conditions around midday Wednesday to get Honor to the IHS emergency room, about 5 miles from the ranch. Rose called ahead to stress the urgency of the matter.

“I told them Gary was going to bring in my grandson, who was very sick,” she recalled. “I said, ‘Please admit him. We don’t want him out on the roads.’ And they said they would look at him and make the decision when he got there.”

'They wanted to get him out'

Honor was evaluated by Dr. Sarah Leeper, who noted he had a history of asthma treated by medication for wheezing and shortness of breath. She also noted his flu symptoms and was told he had likely been exposed to influenza at home or school. He tested negative for COVID-19.

Honor’s vital signs were stable, but he had an elevated heart rate of 122 beats a minute. His oxygen saturation was 95%, considered normal, though Gary insists the percentage was lower before they patted Honor on his back to loosen up phlegm.

Honor rated his chest pain as 6 out of 10, which Leeper noted was likely due to muscle strain from repeated coughing or possible lung irritation from the flu. A chest X-ray demonstrated bronchitis and patches of infection in his lungs.

Leeper prescribed Tamiflu for five days and told the family that Honor should continue using his inhaler, adding that they should “return to the ER for new or worsening symptoms.” She wrote in the chart: “Careful return to ED (emergency department) instructions given.”

Registered nurse Eric Miller documented the discharge at 2:15 p.m. and noted: “Provider informed of discharge vitals – OK to proceed with discharge, aware of lower O2 (saturation).”

“It seemed to me that they wanted to get him out,” said Gary Whipple. “They wanted to diagnose him and get him out. Getting back home was a challenge. The wind was blowing the snow into drifts, so I had to take the traction control off and put the truck in four-wheel drive to make a path to get us home. We got stuck at the gate and had to walk to the house.”

Once home, Honor took his medicine and showed signs of improvement. But a few hours later he was back to feeling miserable.

“I was like, ‘Why don’t you play your game?'” Gary recalled. “That’s when I could tell he was getting worse because he just sat there for a little bit and said, ‘No, I think I want to rest.’ And he laid down and he didn’t seem like himself. The coughs were painful for him.”

Health worsened with the weather

The following day, Thursday, Dec. 15, Honor did little more than lay in the recliner with his blanket, racked by coughs. Brooki Whipple talked to her mother on the phone, worried about what the ensuing hours would bring.

Cordier-Beauvais, attending a conference in Rapid City, tried to contact tribal officials to get the road cleared near Whipple Ranch on BIA Highway 1. There was no other way to get her grandson to the ER if needed. Brooki made calls to Winner, 40 miles away, for emergency services, with no luck.

Oliver, whose tribal duties included emergency preparedness and response, was attending the Lakota Nation Invitational basketball tournament in Rapid City along with Scott Herman, the tribal president.

Cordier-Beauvais said her calls to Oliver and Herman went unanswered. At 8:17 p.m., she texted Oliver that Honor’s condition was getting worse and that “he’s not doing well at all. Is there anyone who can go to Whipple Ranch and help my daughter?”

More than 40 minutes later, at 8:58 p.m., Oliver responded via text: “They’re on their way out. Be there in about 25 minutes or so.” He was referring to a snow plow redirected from Rosebud Sioux Tribal Airport, about 6 miles away and traveling 20 miles an hour.

Rose responded three minutes later: “Hurry. My grandson’s not breathing!”

'We felt him getting cold'

The scene at the Whipple Ranch deteriorated into panic.

Attempts to get Honor to the bathroom were interrupted by what appeared to be a seizure as he collapsed on a rug in the living room, not far from the family’s Christmas tree.

“We were feeling his legs while he was in the recliner to make sure he was OK, and we felt him getting cold,” said Brooki. “On the way to the bathroom, he collapsed on the floor, and I watched as he stopped breathing.”

At 8:57 p.m., Gary and Brooki Whipple called Rosebud Sioux Tribe 911 and spoke with dispatcher Samantha Spotted Tail, who advised them to start CPR.

By then Cordier-Beauvais and Frani Beauvais had gotten word to Shorty Jordan, a tribal employee who was acting independently that night, to plow BIA Highway 1 near the ranch in Two Strike. But snow was still drifting.

At 9:20 p.m. Spotted Tail contacted the Rosebud Ambulance Service and was informed that “medics are stuck on the road.”

Oliver said one of the tribe’s vehicles had to tow the ambulance to reach the ranch, which is offset from the highway. Time was not on their side.

'Somebody's baby is going to die'

Gary Whipple was performing CPR when paramedics arrived around 9:50 p.m. Honor was still not breathing. Dark brown fluid from his nose and mouth left a stain on the rug.

The EMTs continued resuscitation efforts as they loaded him into the ambulance and headed to the hospital 3 miles away. Gary rode along with the boy he considered his son.

“I just felt sick,” he said. “I felt nauseous. I felt pain. I have bad anxiety, and I spent most of that ambulance ride trying to battle a panic attack. And when we got to the hospital, I kind of collapsed. My legs felt like they couldn't hold me up. I remember sitting in a chair and just praying and praying. Then a doctor came out and pulled me aside and said, ‘He’s gone.’”

Resuscitation efforts at the hospital lasted 12 minutes. Honor was declared dead at 10:26 p.m. An autopsy later revealed the cause of death as acute bronchial pneumonia due to Influenza A.

Gary was too shaken to call Brooki, so he asked the doctor to do it. Her sadness quickly turned to anger as she pondered what could have gone differently that night.

“I know it was hard,” said Brooki. “It was a really bad storm. But there are so many things that could have prevented this from happening. The tribe has gotten money from the federal government that could have been used to purchase equipment or have a better emergency planning system like they have in other cities and reservations. If you don’t prepare for these things, somebody’s going to die somewhere. Somebody’s baby is going to die.”

State, tribal officials defend actions

Oliver doesn’t deny that better machinery could have made a difference. But he said it’s unfair to blame tribal officials for a large-scale extended blizzard that replaced snowdrifts as quickly as crews removed them.

“This was a storm that dumped a lot of snow really fast,” said Oliver, who is now in charge of dam safety for the tribe. “It was wet snow, heavy snow. And the wind swept everything back in after roads were cleared earlier that day.”

As for the plow operator who failed to get roads cleared to Whipple Ranch in time for the ambulance, Oliver said the man experienced rough days in the aftermath of Honor’s death.

“He was hurting,” said Oliver. “He was sad. He said, ‘I don’t know if I can do this.’ Nobody knows that side of it. They act like no one has feelings. We did our best, and everybody was angered because we couldn’t do it. Our equipment started breaking down in the cold.”

On Dec. 16, the day after Honor died, Herman posted a presidential address video to Facebook from The Monument arena in Rapid City, where basketball was still being played. He announced that the tribal council had issued a disaster declaration and reached out to state and federal officials for equipment and other resources.

“We are aware of the many challenges this weather has brought upon our community,” Herman said in the video. “We know that clearing the roads is a priority, because it makes access to all the other services possible.”

Herman and other tribal officials expressed frustration at the response from Noem and the Department of Public Safety as the storm raged, claiming the governor should have called in the National Guard earlier or sent heavy-duty equipment. Ian Fury, Noem's chief of communications, dismissed those claims at the time as part of a “false narrative.”

DPS released a timeline that showed a coordination call regarding the storm with all the state's tribes on Dec. 12. It said Rosebud officials were connected to a snow removal contractor on Dec. 17 through the Office of Emergency Management and that the tribe indicated later that day that it had “no other resource requests.”

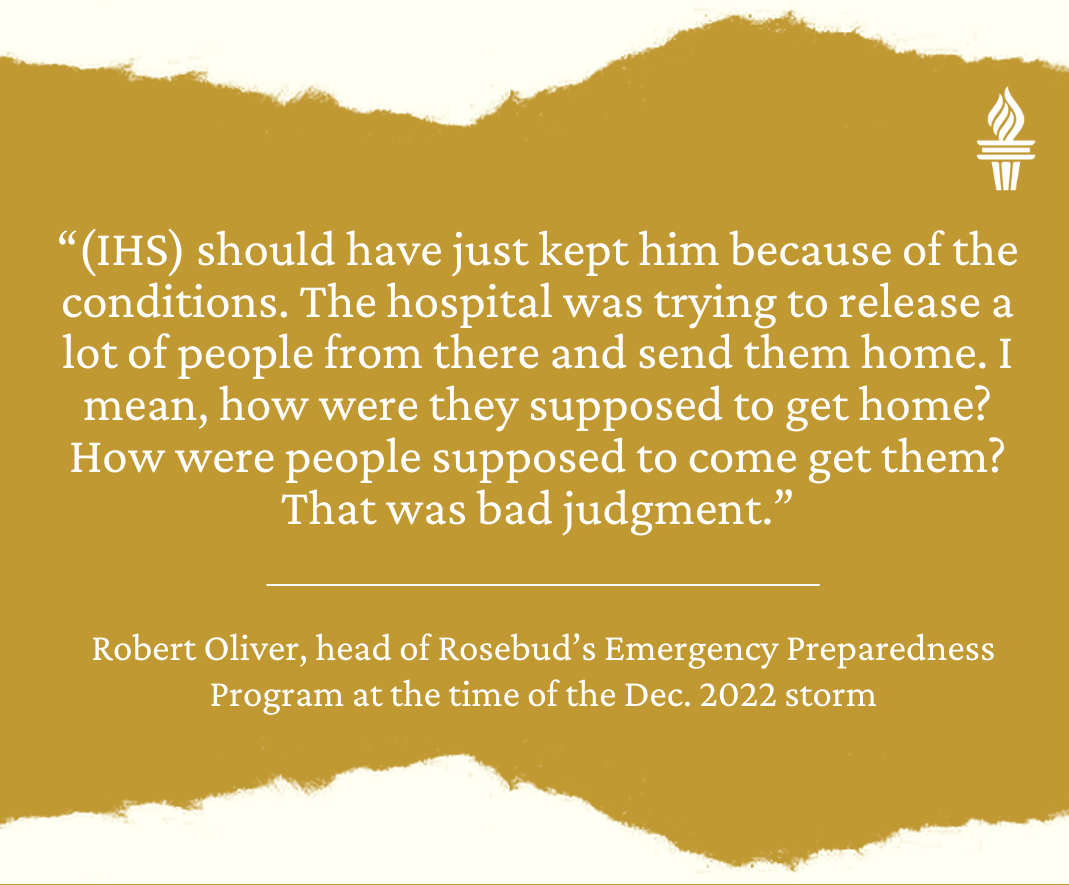

One thing that Rose and tribal officials agree on is that Honor should not have been released from the hospital Dec. 14, given the severity of weather conditions. Oliver said the tribe reached out to IHS in the days following Honor’s death and asked them to keep patients longer if possible.

“They should have just kept him because of the conditions,” said Oliver. “The hospital was trying to release a lot of people from there and send them home. I mean, how were they supposed to get home? How were people supposed to come get them? That was bad judgment.”

Celebration of healing and hope

Fallout from the blizzards continued through the end of December 2022, delaying Honor’s funeral until the new year. There was a Jan. 6 caravan starting at the Rosebud Casino and an evening service at Fr. Paul Hall church in Mission, followed by the funeral the next day.

A card handed out at the service showed Honor in various stages of joy: swimming with his cousins, playing basketball, catching a fish and frolicking at the beach.

“Live your life, laugh again, enjoy yourself, be free,” read the accompanying poem. “Then I know with every breath you take, you’ll be taking one from me.”

On Oct. 27, 2023, the day that would have been Honor’s 13th birthday, his classmates threw him a party. They painted stones with themes from his life and laid them next to the gravesite while sharing stories and singing “Happy Birthday.”

Rising above the burial mound was a medicine wheel, a sacred symbol of knowledge and hope, and healing for those who seek it.

Honor’s friends then gathered at the home of Melissa LaPointe, his former teacher, where they played games and feasted on some of favorites: Fanta orange pop, chicken nuggets, ramen noodles, Jolly Rancher candy.

It was a bittersweet occasion for Cordier-Beauvais, whose pleasure at seeing her grandson celebrated was tempered by lingering resentment and her belief that his death could have been prevented.

From the time he moved from Denver and the reservation became his home, Honor made his presence felt. He still does.

The plan was to brighten his future by surrounding him with love, family and faith. It soon became apparent that the lives of those around him would be the ones most profoundly impacted, by allowing a young boy to dream.