From a riverbank or roadside, South Dakota’s waterways appear placid and picturesque.

The tree-lined Big Sioux River meanders smoothly and silently along the state’s eastern border. The mighty Missouri rolls below cliffs and ridges on a curvy path through the center of the state. Rapid Creek glistens with crystal clear water as it flows out of the Black Hills through Rapid City and onto the western prairie.

But those impressive images don’t tell the unsettling true story of South Dakota’s rivers. A look beneath the surface reveals that from east to west and north to south, almost every waterway in the state serves as a dumping ground for human, agricultural and industrial wastes with dangerous consequences for human health.

In a first-of-its-kind analysis, South Dakota News Watch reviewed more than 100 water permits and inspection reports, examined a dozen scientific studies and interviewed nearly three dozen people to investigate the quality of state rivers and identify threats. In a two-week, multi-part series, News Watch will outline the damage being done to state rivers, reveal the sources of pollution and examine what can be done to turn the tide of contamination.

The reporting showed that South Dakota waterways are under siege from the impacts of human activity. From urban runoff and litter, to municipal and industrial wastewater facilities that release millions of gallons of treated sewage and other chemicals into rivers each day, to agricultural operations that send nutrients and dangerous bacteria into waterways in large quantities, most South Dakota rivers are impaired due to pollution. In some cases they are simply unsafe.

Examples of polluted waterways where human health may be at risk:

- Whitewood Creek and the Belle Fourche River are awash in toxic arsenic.

- The Cheyenne River is polluted by both uranium and mercury.

- Rapid Creek and the Big Sioux River, according to new research, hold genetic markers for mutated forms of E.coli bacteria, known as shigatoxigenic E.coli, that can lead to bloody diarrhea, kidney failure and death, even from ingestion of a single drop of contaminated water.

“The problem with all pollution is that it’s OK the first year, but over time, a few decades later, you say to yourself, ‘Maybe we should never have done this,’” said Dana Loseke, a retired dairy plant manager who is a leader in the Friends of the Big Sioux River advocacy group. “All pollution goes somewhere: it ends up somewhere.”

Almost 50 million gallons dumped daily

In many cases, the destination for that pollution in South Dakota is the state’s rivers and streams.

South Dakota News Watch reviewed permit and inspection data for South Dakota’s 20 most populous cities and found that 49.2 million gallons of treated wastewater are dumped into state rivers by those cities each day. That equals the capacity of 8,200 tanker trucks stretched out on Interstate 90 roughly from Sioux Falls to Kimball.

State records indicate that millions of gallons are dumped daily along the full length of the Big Sioux River, into the James River from Huron to Mitchell, into the Missouri River from Mobridge to Yankton, and into Rapid Creek east of Rapid City. During the tourist season, even the mountain-fed stretch of Spring Creek below Hill City is subjected to 250,000 gallons of treated wastewater per day as it flows toward Sheridan Lake.

Those discharges are separate from the millions of gallons of treated industrial wastes from industries such as meat processors in the east and a few industries in the west, such as Pete Lien and Sons gravel plant that dumps into the Cheyenne River near Oral.

While most of the discharge water meets state pollution limits, it still contains small amounts of fecal coliform, ammonia, nitrates and other pollutants. In addition, wastewater treatment plants do not remove antibiotics in human waste, nor do they filter out household chemicals flushed down toilets or sinks or motor oil and other contaminants that flow into urban storm sewers.

During times of heavy rains and high flows, South Dakota rivers can dilute pollutants, but during summer, winter and droughts, “there are times when a significant percentage of the water in the river is discharge water,” said Jay Gilbertson, head of the East Dakota Water Development District.

In the east, the main causes of pollution are urban development, nutrient runoff from row crops such as corn and soybeans, and wastewater from industries including pork, turkey and beef processors but also cheese plants and metal fabricators. In the west, the common culprits are rural septic systems, sediment runoff from ranches, and extensive historic, ongoing or proposed future mining for gold and uranium in the Black Hills.

The state’s massive agriculture industry is a major economic driver but also a big contributor to river pollution.

The number of concentrated animal feeding operations continues to rise in South Dakota, with more than 440 CAFOs now permitted to raise 10 million pigs, hogs and fowl each year. Drainage tiling is expanding farmable acres in the state and often directs rainwater and nutrients toward waterways. Many farmers and ranchers are working to reduce runoff and pollution, but almost all efforts to encourage low-impact agriculture or urban development in South Dakota are not required, relying instead on voluntary or incentivized participation that has shown modest results at best.

Industry growth has heightened pollution concerns

Municipal and industrial wastewater treatment plants are regularly inspected, yet the state relies on self-reporting of pollutant levels and wastewater discharge data by permit holders.

Failure to record or report data in a complete and timely manner is a frequent violation found during inspections, as are violations of limits on dumping of ammonia, E.coli bacteria, acidity level, nitrates and temperature of discharge water.

Meanwhile, industry growth has led to heightened pollution and violations of wastewater quality standards are common.

The South Dakota News Watch review uncovered numerous examples of industry problems, including:

• The Valley Queen cheese plant in Milbank had 1,002 water quality violations from 2005-2008 and 151 more violations from 2008 to 2011.

• In 2015, the Bel Brands cheese plant in Brookings drew violations from the city of Brookings after city employees were put at risk from potentially explosive levels of hydrogen sulfide released by the plant, which has had numerous other violations.

• The Smithfield Foods pork plant in Sioux Falls was fined in 2011 after repeated discharge violations that included release of three times the allowable limit of ammonia. The plant also was blamed in part for a fish kill on the Big Sioux River in 2012. On Aug. 15 of this year, state regulators said the plant experienced a treatment system failure that discharged ammonia levels high enough to threaten fish in the Big Sioux.

Those and other companies tend to improve processes after being flagged for violations by the state. However, the state testing process, which requires most industries to meet discharge limits of eight known pollutants, does not capture data on whether other industrial chemicals are entering the waterways. Major cities and industries typically have pre-treatment systems to remove toxic chemicals, but any that slip through are not be removed by subsequent wastewater treatment processes.

Concerns over water quality in the Big Sioux River have escalated of late due to a plan by the Agropur cheese plant in Lake Norden to expand operations and begin dumping 2 million gallons of treated industrial wastewater into the Big Sioux River daily.

Catastrophic pollution releases in South Dakota are rare and often heighten public awareness over pollution, such as after the 2010 wastewater treatment system failure in Sioux Falls that dumped 65.3 million gallons of raw and partially treated sewage into the Big Sioux River. Most river pollution in the state, however, comes in small doses from widely varying sources that add up over time.

Cities work to improve treatment processes

Municipalities are in an almost constant quest to improve their processes and water treatment equipment, but improvements are expensive and easily reach into the millions of dollars.

Despite best efforts, numerous wastewater permit violations occur in South Dakota, including:

- The city of Pierre had 44 violations in 2014 mostly for fecal coliform, or E.coli, and 17 effluent violations from September 2015 to March 2016 for fecal coliform, total coliform, pH and residual chlorine.

- Fort Pierre was placed under a state order to fix its system after numerous permit violations, ranging from failure to report accurate data to 25 effluent violations from 2010-15 that included several exceedances of ammonia limits.

- The city of Elk Point in Union County had 52 effluent violations from 2006-2015, and 11 more in 2017. Two violations came after the city built a new wastewater holding cell as ordered by the state.

Some consequences of abusing rivers appear far from the borders of the Rushmore State and only after decades of polluting.

While Iowa takes most of the blame, nutrient loading of Great Plains waterways that flow into the Missouri River, then to the Mississippi River and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico are causing a literal dead zone in the Gulf that is steadily increasing in size. Algae blooms in the burgeoning hypoxia zone deprive the waters of oxygen and have decimated marine life and fish populations and hampered some coastal industries.

“As we’ve increased our inputs of nutrients to the landscape so we can grow corps, that has consequences,” said Christopher Jones, a University of Iowa professor who studied the impact of agriculture on the Gulf dead zone.

The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation in west-central South Dakota has been under a fish-consumption warning since the 1970s due to mercury pollution, and studies show the river is also contaminated with uranium and arsenic from historic mining upstream.

“We’re not very good stewards of the land,” said David Nelson, environmental director for the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. “Until pollution starts impacting a place or a people to where they don’t have a drinking water source anymore, things will just continue as they are. Until then, it’s all dollar-driven.”

In one way, South Dakota is fortunate that most municipalities – including the bulk of East River cities and towns – get their drinking water from wells that tap into as yet unpolluted aquifers. Some cities, however, do use surface water for drinking, including Rapid City, Mobridge, Fort Pierre, Oacoma and Chamberlain. If Sioux Falls continues its rapid growth, it also may someday rely on the Big Sioux River for drinking water.

South Dakota and the nation have come a long way in improving water treatment and testing processes since approval of the federal Clean Water Act in 1972, which set limits on direct polluters but did nothing to reduce indirect pollution from sources such as agriculture and urban development.

Prior to the act, many cities, including in South Dakota, dumped untreated or partially treated sewage directly into waterways. One report from the state of South Dakota showed that municipalities along the Big Sioux River spent $176 million between the 1950s and early 2000s to improve their treatment plants. Both Sioux Falls and Rapid City are considering multi-million-dollar upgrades to their plants in coming years.

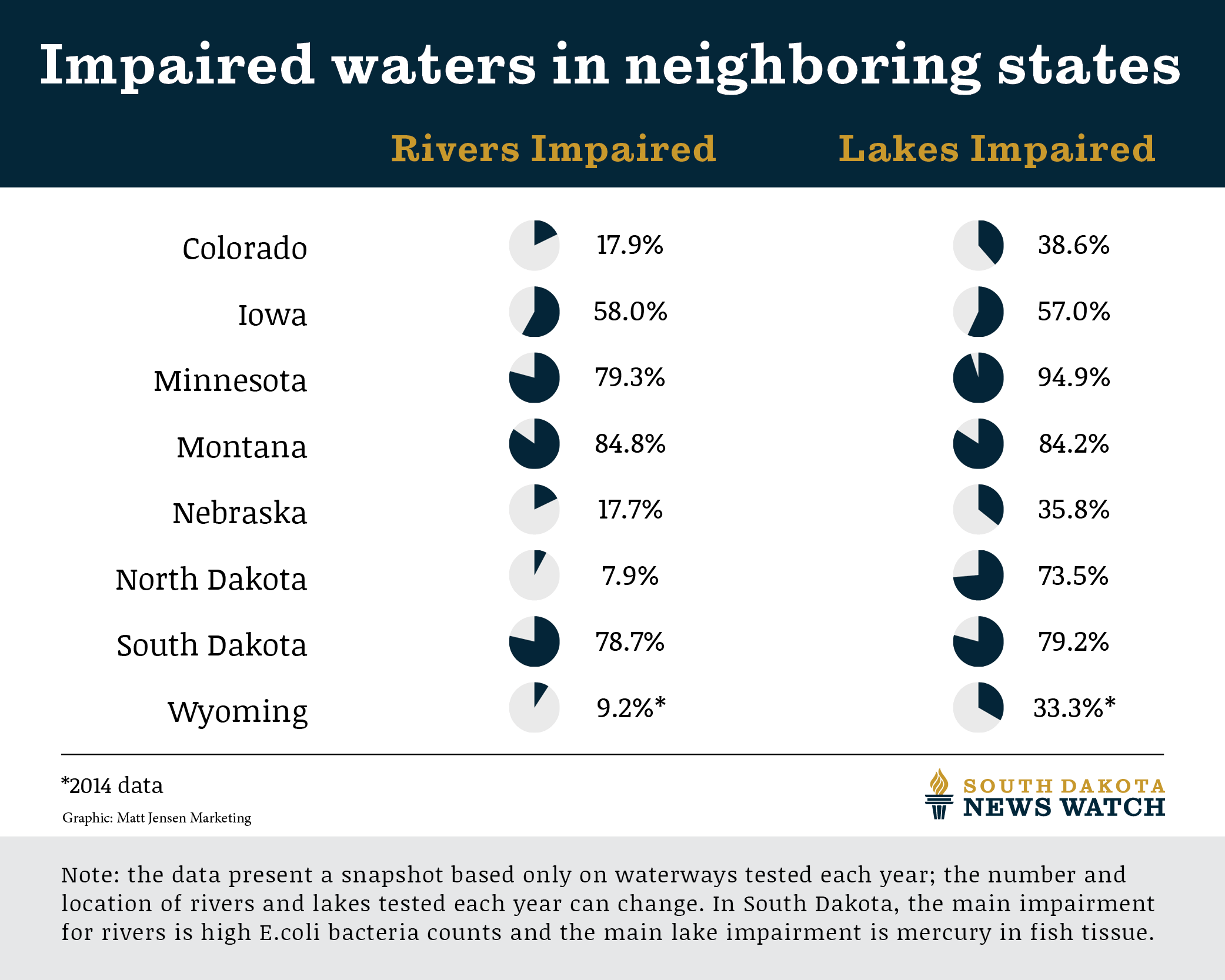

However, according to a News Watch data review, in the 10-year period from 2006 to 2016, the number of South Dakota rivers considered “impaired” by the federal government has grown significantly, increasing 22 percent during that decade. Nearly three quarters of South Dakota river miles tested in 2016-17 were considered impaired by the federal government.

Recent research indicates that the mixing of pollutants from such a wide variety of sources has made South Dakota rivers a mixing bowl where contaminants, including some potentially deadly microbes, can flourish.

State regulators, municipal and industry treatment operators and scientists who study the outcomes are all looking for ways to safely treat wastes and limit runoff to safely meet the needs of a growing human population. The state hopes to increase staffing of its permit and inspection team, and regularly makes low-interest loans to cities in need of system improvements.

Agricultural producers are increasingly responding to outside pressure and their internal commitment to reduce their impact on the earth. Residents of both rural and urban communities are slowly becoming more conscious of how their actions affect the environment.

Ultimately, though, increasing protections for South Dakota rivers will largely boil down to money and future investment, a fact that presents a major challenge to a low-population state that is fueled mainly by sales tax revenues.

“There’s more science coming and it’s going to cost us more, but if we want that resource to go on into the future and be available to our children, we have to keep improving our game.” said Dave Van Cleave, superintendent of the Rapid City Water Reclamation Facility.

Find much more on this topic, including an in-depth look at the wastewater dumped by the 20 biggest cities, a look at the effectiveness of wastewater treatment processes, a review of recent water quality studies and an examination of the impacts of agriculture and other indirect sources of pollution, at sdnewswatch.org.