A zero-tolerance testing approach to reducing drunken driving and other alcohol-related crimes that started in South Dakota could broaden its reach nationally, despite concerns from critics that it restricts the constitutional rights of some participants.

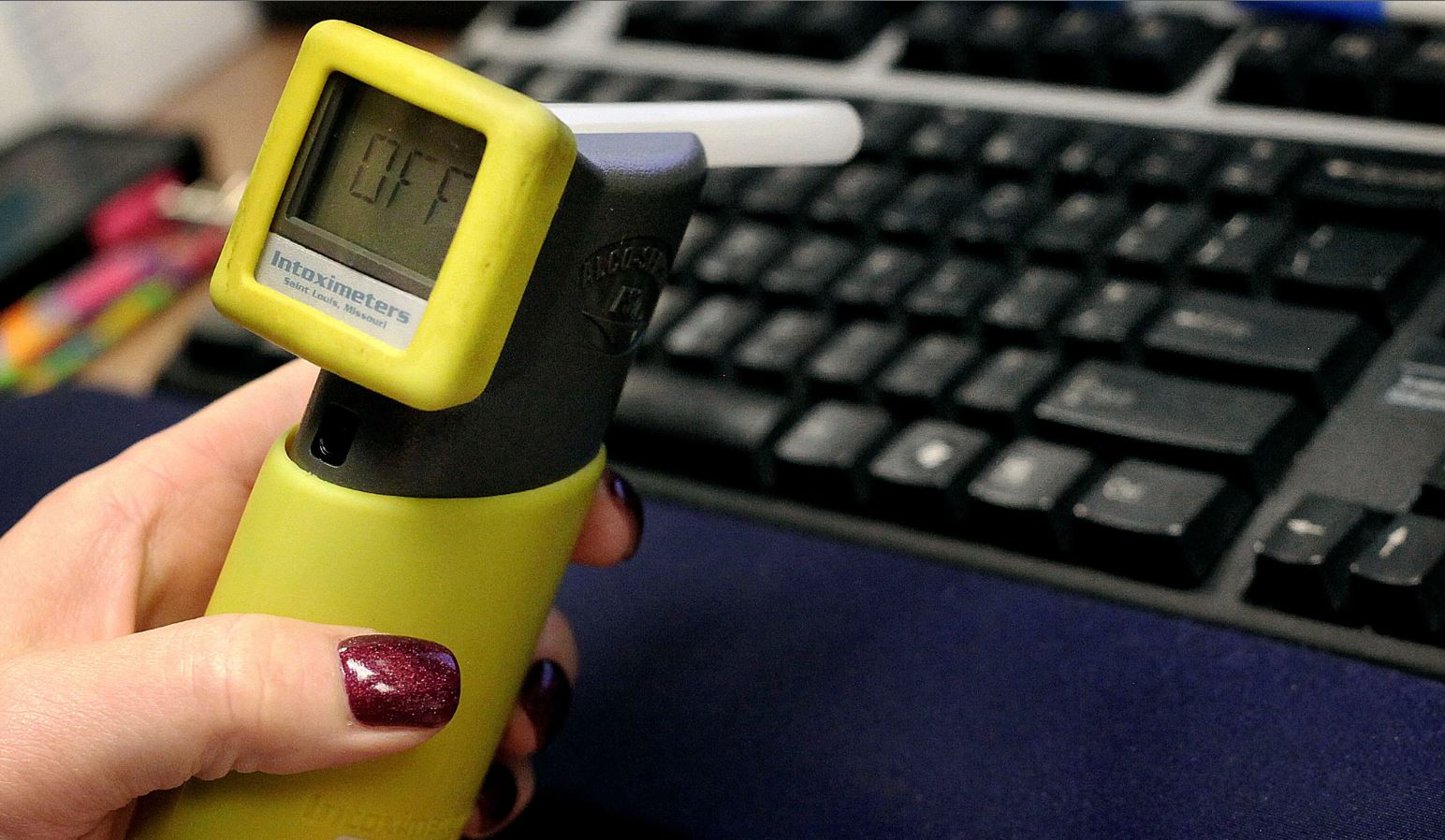

The 24/7 Sobriety program, pioneered by former South Dakota Attorney General Larry Long, requires offenders to submit to twice-a-day breathalyzer tests or remote monitoring as a condition of pre-trial bond or sentencing agreement. Failure to remain sober means the participant is sent to jail, a no-nonsense doctrine that has coincided with a decrease in DUI and other alcohol-related offenses, according to independent studies.

“That’s why it works,” Long said of 24/7 Sobriety, which is used in South Dakota, North Dakota and Montana and is in place in four other states as pilot programs. “These people know that if they show up and blow hot, they’re going to jail.”

South Dakota is a testing ground for lawmakers and policy analysts seeking to reduce the effects of alcohol abuse, which kills more than 140,000 individuals nationally each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with an annual cost of nearly $250 billion due to lost work productivity and health care expenses. Since 24/7 Sobriety started in 2005, there have been more than 39,000 participants in South Dakota and nearly 12.5 million tests administered, with a pass rate of 98.8%, according to the attorney general’s office.

All but four South Dakota counties (Buffalo, Jones, Oglala Lakota and Todd) utilize the program, which focuses on repeat offenders and is largely self-funded because the cost of testing is passed on to participants. The original system, which targeted convicted drunken drivers, has expanded to include other cases involving alcohol or drugs, including cases involving abused or neglected children, and as a stipulation for maintaining a work permit.

In most counties, the first time the participant fails a test or doesn’t show up, he or she is jailed for 12 hours, followed by 24 hours for a second violation and 48 hours for a third. Any further violations are sent to a judge, who can revoke bond or the sentencing agreement and put the offender behind bars for an extended period.

The next test for the program is to see if 24/7 Sobriety can catch on nationally. U.S. Rep. Dusty Johnson, R-South Dakota, is co-sponsoring bipartisan legislation to offer federal grants for states to adopt the intervention model, while also encouraging further study on its effects on drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

The SOBER Act (Supporting Opportunities to Build Everyday Responsibility) would help defray administrative costs for equipment that includes not just breathalyzers but also for urinalysis, drug patches, monitoring bracelets and ignition interlock devices, which prevent a vehicle from starting unless the driver passes a breath test.

Johnson noted that those awaiting trial or serving a suspended sentence can maintain employment and be with family if they stay away from alcohol and drugs, which in many cases was a factor in their criminal behavior. Ideally, mental health counseling and other services are part of the recovery process, rather than expecting offenders to “clean up” behind bars.

“I’m amazed at how ahead of its time South Dakota was,” said Johnson, who didn’t offer a timetable for when the bill might reach the House Judiciary Committee. “Now, most Americans understand that the best way to deal with addiction is not simply to throw someone in prison. Treatment and day-to-day accountability need to be a part of that journey. We’re talking about that every day in (Washington D.C.) now, but South Dakota was talking about it decades ago, and put together a pretty robust program with pretty good outcomes.”

Opponents point to civil rights issues

Critics claim those outcomes have come at the cost of constitutional protections for participants, many of whom are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of a crime. There are also questions about passing the cost of the program on to participants who might not be able to afford it in addition to having to pay for attorney fees, fines, mandatory counseling and other costs associated with their case.

The breathalyzer tests cost $2 a day, while more expensive options – remote breath testing for $5 and SCRAM (Secure Continuous Remote Alcohol Monitoring) bracelets at $6 a day – allow participants to avoid the twice-daily trip to the county jail or sheriff’s office for testing.

“That’s a luxury that many of our clients can’t afford,” said Traci Smith, who heads the Minnehaha County Public Defender’s Office. Though the program works in some cases to keep people out of jail, Smith said, she’s concerned that expanded use of 24/7 Sobriety makes it a catch-all that supersedes more suitable forms of rehabilitation.

“I do think it’s a good tool, but I don’t know that it’s a universal tool that should replace everything else in the toolbox,” said Smith, who started as a deputy public defender in 1999. “It’s not the same as treatment, and I think sometimes people outside of the treatment world forget that. Everything can’t always fall back on the jail or law enforcement to fix our problems.”

Smith has seen enough cases to know that the program’s positive effects are often temporary, and sometimes based on participants getting around the rules.

“What clients tell me is that once they get their schedule, they drink just enough to know when they get around the hours and they don’t get held,” Smith said. “Rather than addressing the real issue, which is the trauma behind the addiction, they’re just learning to play the game.”

The American Civil Liberties Union filed a federal lawsuit earlier this year challenging the 24/7 Sobriety program in Teton County, Wyoming, claiming twice-daily breath tests amount to “warrantless search” and violate the Fourth Amendment. The complaint also alleged Eighth Amendment violations for excessive bail due to fees that disproportionately impact indigent participants.

In April, a district judge denied the motion for a preliminary injunction to temporarily halt the program in Teton County, which the ACLU targeted because it included first-time defendants rather than just repeat offenders. Stephanie Amiotte, the ACLU’s legal director for South Dakota, North Dakota and Wyoming, said the 24/7 Sobriety case is “pending and active” and that her organization could pursue similar lawsuits in other states.

“Treatment programs are typically the best indicator of whether somebody is going to have a relapse or whether they’re going to contribute to their sobriety,” said Amiotte. “Throwing people in jail, causing them to lose their job, making them pay money that they don’t have, really isn’t the best way to effect change when somebody has a substance-abuse issue.”

Supporters, however, point to encouraging data from groups such as the RAND Corporation, a California-based policy think tank, which found a reduction in DUI arrests and domestic violence arrests in states that adopted the model.

A 2020 study by the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management published by RAND found that the probability of a 24/7 participant being re-arrested or having probation revoked within 12 months of being arrested for DUI was nearly 50 percent lower than that of non-participants.

“These findings provide support for ‘swift-certain-fair’ approaches to applying sanctions in community supervision,” the study’s authors concluded. “They also provide policymakers with evidence for a new approach to reduce criminal activity among those whose alcohol use leads them to repeatedly threaten public health and safety.”

Vision for new approach takes shape

Larry Long grew up in Bennett County and spent 18 years as a prosecutor there in the 1970s and 80s, dealing with a steady tide of alcohol-related infractions, many involving repeat offenders.

Those caught drinking while out on bond faced penalties such as losing their driver’s license, their vehicle or entering mandatory treatment, but that failed to deter the most chronic abusers of alcohol from landing back in custody.

“The sheriff and I were sitting around one day trying to figure out how we can make some room in our jail,” Long told News Watch. “We hit upon the idea of testing people twice a day to enforce one standard rule, which is you don’t drink while you’re out on bond. The jail was across from the sheriff’s office, so we would march them literally across the hall and put them behind bars.”

Long likened the experience to touching an electric fence: “You never touch it purposefully a second time,” he said. “What we discovered was that we could keep hardcore drinkers sober for two to three months at a time, allowing for better habits to take hold.”

He moved to Pierre to become deputy attorney general under Mark Barnett in 1991 and took the Attorney General position in 2003, with fellow Republican Mike Rounds as governor. When Rounds formed a corrections working group to deal with rising incarceration rates, Long saw a chance to test the 24/7 Sobriety program with a broader scope. In 2005, he introduced the concept as a pilot program in three counties – Minnehaha, Pennington and Tripp – to see if the success in Bennett County could translate statewide.

Byron Nogelmeier, now the state 24/7 Sobriety coordinator, served as Turner County Sheriff at the time and recalled being skeptical of Long’s vision.

“He came to a conference of the South Dakota Sheriffs’ Association and brought it to the table, explaining how it had worked in Bennett County,” said Nogelmeier. “Most of us walked out of there, thinking, ‘Wow, how’s this going to work?’ But the more information he fed us and the more we saw of the pilot program, the more we became believers.”

Long enlisted Bill Mickelson of the South Dakota Highway Patrol to run the program, which involved raising money for equipment and compiling data on alcohol-related convictions. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that South Dakota traffic fatalities involving alcohol impairment dropped from 71 in 2004 to 34 in 2008.

By then, the Legislature had passed a law to offer the program statewide, providing $350,000 in state funds in 2007 and $400,000 in 2008 to target chronic drunken drivers who ignored pre-trial provisions and consumed alcohol while out on bond. Costs for the program were soon passed on to participants, and counties were given the option of implementing the system.

“We limited it to (second offense) DUIs or higher, focusing on people who had been arrested for DUI and had a prior conviction within 10 years,” said Long. “Judges started to see what we had seen in Bennett County, and more and more of them got on board.”

‘It probably saved my life’

By the time David Whitesock moved from North Dakota to South Dakota and started working at a Winner radio station in 2005, he already had four DUI arrests, three failed college stints, an eviction from his apartment and a pink slip from his last job. He struggled with anxiety and depression that fueled his addiction to alcohol.

When he picked up his fifth drunken driving arrest three months after arriving in Winner, he expected to post bail like he had in the past and show up for his next appearance.

“They said, ‘No, we have a new plan here,’” Whitesock told News Watch. “They told me that I could leave when I blew zero and as long as I continued to blow zero two times a day, I could keep working until I was sentenced. That sort of opened my eyes.”

For three months, while working as a broadcaster, he would head to the police station, which was right across the alley from the radio station at 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. to blow into a tube.

“I’d put on a six-minute song, something by Led Zeppelin, run out the back door and the (officers) knew I was coming,” he said. The one time he forgot, he tried to talk his way out of it but was thrown behind bars until his sentencing date.

When that day arrived, in September of 2005, he entered the Tripp County courtroom of Judge Kathleen Trandahl wearing an orange jumpsuit, feeling out of sorts and out of chances.

“I will never forget that day,” said Trandahl, who retired as a judge in 2016. “He looked like a tomcat that had been pulled behind a pickup for two weeks. He was markedly in trouble, just by looking at him.”

Trandahl was familiar with the 24/7 Sobriety Program because her circuit included Bennett County, and she had lobbied to become part of Long’s pilot program. She saw the zero-tolerance doctrine as well-suited for Whitesock, who despite his struggles had strong family support and was educated enough to understand the weight of the court’s expectations.

“It was glaringly obvious that the criminal justice system had failed him in North Dakota,” said Trandahl, noting that the state did not have 24/7 Sobriety at that time. “He had somehow managed to amass four DUI convictions, plus other crimes, and had been in and out of jail. And yet with all of that, he had never been to treatment, he had never been on probation, and there had been no court supervision. He was offered no help whatsoever, and I just felt that he was owed that opportunity by the court.”

She handed Whitesock a 5-year sentence of supervised probation and two years of prison suspended. He received in-patient treatment at the Human Services Center in Yankton for 147 days until he found a spot at a sober house in Sioux Falls that the judge signed off on, within the framework of the 24/7 Sobriety system.

For the next 947 days, he rode his bike twice a day to the Minnehaha County Building for his breath tests while working a job and attending 12-step meetings. As the toxins left his body and his head cleared, he charted a path to enroll at the University of South Dakota with the judge’s blessing.

“When you get up every morning at 6 a.m. and ride 26 blocks, then ride your bike back and do the same over again that night, it creates a certain level of discipline,” said Whitesock. “That structure, given what my life was like before, was a game-changer for me.”

He met his future wife at USD and worked his way into law school, weaning himself off 24/7 Sobriety into a more conventional form of probation. On Aug. 3, 2013, along with his family, he returned to the courtroom in Winner, this time for his Oath of Attorney after passing the bar, and Trandahl administered the oath.

He worked as a data analyst for Face It Together, a Sioux Falls nonprofit that works to combat drug and alcohol addiction, and in 2020 founded his own New York-based company using data surveys to “measure wellbeing and quality of life relative to the effects of addiction.”

Whitesock sees 24/7 Sobriety as a shock to the system but not the only answer for chronic offenders. He and Trandahl both admit that 947 days of twice-daily tests became too much of a crutch, and he needed to test his sobriety while still having the safety net of probation and random tests.

But Whitesock also considers it a twist of fate that he happened to be in one of the counties that was part of Larry Long’s pilot program when his fifth DUI occurred after moving to Winner from North Dakota.

“Tripp County became part of the program because of Judge Trandahl in February of 2005, and I showed up in June,” he said. “It was in the two largest counties in South Dakota and then one little county, squished between Native American reservations, and that’s where I ended up, after a decade of personal destruction. It probably saved my life.”

Different paths to achieving sobriety

Rep. Johnson supports South Dakota’s 24/7 Sobriety model but concedes that other states might need to find other ways to implement the program The SOBER Act would provide $250 million to states over five years to “create, sustain and expand” their programs and gather data, with a common goal of avoiding crowded jails and decreasing the amount recidivism with DUIs and other offenses.

“I’ve got pretty strong opinions on this issue, but I don’t think all of the wisdom resides in D.C.,” said Johnson. “So rather than impose my opinion on the states, we wanted to give them the flexibility to chart their own course. Maybe we’ll all do it a bunch of different ways and we’ll be able to learn which is best through time and data.”

Johnson’s bill is supported by the National Sheriffs’ Association and the Niskanen Center, a Libertarian-leaning think tank in Washington. But other groups have been a tougher sell. MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) has criticized the 24/7 Sobriety system for focusing not on just impaired driving but alcoholism in general, which they consider too broad a scope.

“Their focus is different,” said Long, who served two terms as attorney general and later became a circuit court judge before retiring in 2018. “Their primary tool is the interlock device that’s designed to prevent a drunk person from driving a car. Our goal is different. We want this person to quit drinking so he’s no longer in the criminal justice system at any level. We don’t want him to drive a car drunk, we don’t want to him to beat his wife, we don’t him to abuse his kids, we don’t want him to pee on the sidewalk, we don’t want to have to appoint a lawyer for him, and we don’t want to have to pick a jury for him. That’s our focus, and it’s cheaper.”

In addition to the states that have adopted 24/7 Sobriety statewide, there are pilot programs either implemented or authorized in Alaska, Florida, Idaho, Nebraska, Washington, Wisconsin and Wyoming.

The Wyoming Legislature passed a 24/7 Sobriety law in 2014 but sparked controversy with a 2019 amendment that broadened the scope of the program to include first-time offenders, which made the breath tests “daily warrantless searches,” according to the ACLU.

A district judge dismissed some of the ACLU’s arguments in denying the motion for a preliminary injunction, writing in his opinion that the plaintiffs “have thrown much due-process spaghetti at the wall in this proceeding, and none of it has stuck.”

What happens next with that case will be watched closely as Johnson builds support for his bill and tries to get it to the House floor, which might become more realistic after the November mid-term elections. What started as an outside-the-box experiment in Bennett County could gain a national foothold if the GOP retakes the majority.

“There’s been a bit of a transformation in thinking, particularly among Republicans,” said Johnson. “Thirty years ago, the dominant thought among Republican policymakers was that the severity of the punishment was enough to deter crime. We now know that it’s the certainty and swiftness of sanctions that change behavior, and this is a positive step.”