Falling attendance and membership at many South Dakota churches has prompted pastors, leaders and elders to look for creative ways to keep people engaged and pursuing a larger purpose.

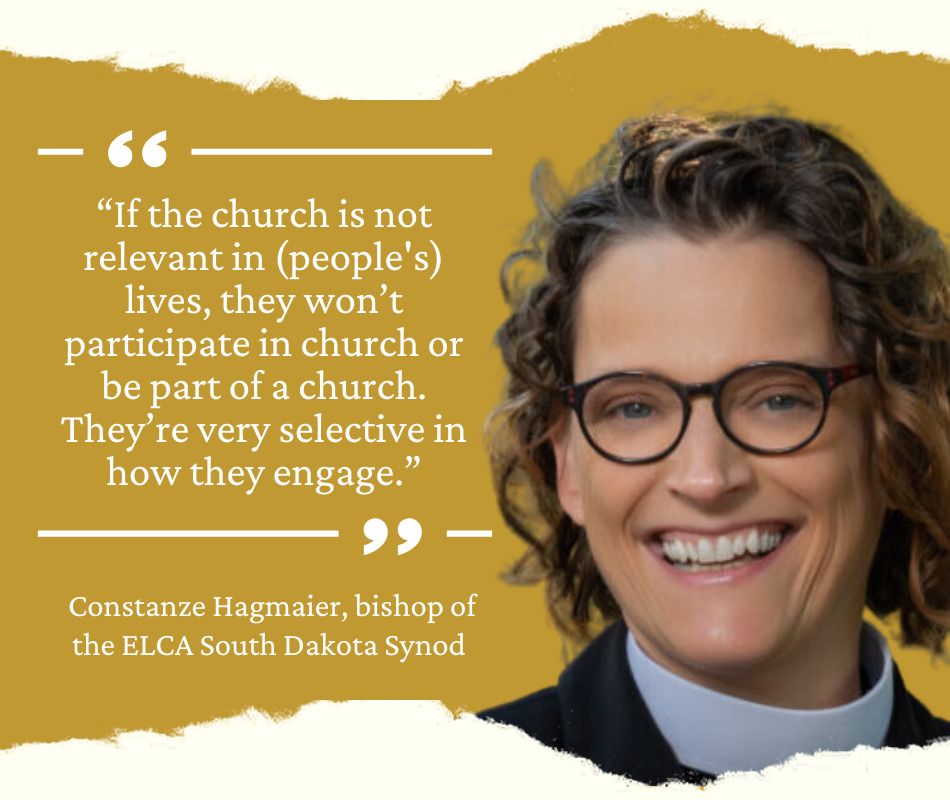

Constanze Hagmaier, bishop of the South Dakota Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, said that includes using technology to allow for remote attendance and encouraging lay church members to take a more active role in spreading the gospel outside the walls of the church.

Churches of all denominations need to be more flexible in the messages they deliver and how they are shared and can only do so through a deep examination of what people are seeking in an ever-changing world, she said.

In some ways, the church must provide the sense that religion is a way to help not only oneself but also the community and the world as a whole, said Hagmaier, who was elected bishop in 2019 and acknowledges it won’t be easy or quick.

More from SD News Watch: Easter Sunday offers break in church attendance decline

“Oftentimes, when we look at civic resources and civic engagements, it’s all about what can I do. It’s all about me, me, me, me, me and how we need to save ourselves. And if we can’t do that, we get frustrated and all these things bubble up and we start pointing fingers and conflict arises,” she said.

“But the church, ideally speaking, has this other voice, this countercultural voice, where if we take ourselves out of the picture and put God at the center, and that’s part of our message, then we can take our own differences away and look at life from a different lens, and work for communal good.”

Church needs to be more relevant

That new reality — and a subsequent effort to align church messages more closely with the needs and desires of individuals — is true for middle-aged or older people. But it’s especially true among children and young adults, who may, or may not, form the backbone of churches and religion in the future, Hagmaier said.

Changing and adapting is critical in reaching and attracting the next generation of South Dakotans who look at the world and institutions with a more critical eye and demand more payback for the time and energy they invest in a church or any organization, she said.

“If we still think we live in the times that we lived in when our forefathers founded the land and the church, and these young people have all the pressing issues that we are not able to talk about, then they won’t be interested,” Hagmaier said. “If the church is not relevant in their lives, they won’t participate in church or be part of a church. They’re very selective in how they engage.”

For example, Hagmaier said, trying to use traditional methods to collect offerings at church may not work for children or young adults.

“If all I do is pass a basket … I’m not sure my kids would make an offering,” said Hagmaier, who has three children. “My kids, they never owned a checkbook and I don’t know that they even carry cash.”

Churches need to adapt and react to changing trends in church attendance very soon due to a breakdown in generational church attendance that could have grave long-term consequences for organized religion, Hagmaier said.

“We’re coming now to a generation where the parents never went to church,” she said. “Right now, 7-year-old children are like, ‘Church, what is that?’”

Yet Hagmaier added that the church cannot and should not be so reactive to cultural changes in society as to lose focus on the core values and tenets of Christianity and the Lutheran church.

“The church has a clear and profound message at which the true God is at the center and from there we reach out to offer an alternative way of life. But if the church loses the focus we become fear driven and operate from a preservative mindset,” she said. “If we believe that in everything God’s at the heart of things we are free to engage in our culture and offer an alternative.”

Catholic diocese adds dedicated position to boost attendance and membership

The Rev. Scott Traynor holds a new position within the Sioux Falls Catholic Diocese called the Vicar for Lay and Clergy Formation. It puts him at the center of new efforts to invigorate church membership and attendance in the diocese.

Traynor said that when Bishop Donald DeGrood took office in 2020, he immediately sought to reduce the trend of declining engagement with the Catholic Church in eastern South Dakota, and Traynor’s new position was part of that effort.

The Catholic Church throughout its history did not need or desire to be too evangelistic in its approach to attracting new members, he said.

“The bishop put forth a very clear vision statement for the diocese: to build a culture of lifelong Catholic missionary discipleship through God’s love,” Traynor said. “That is a very clear and organizational focus for the efforts of our diocese to build up that culture precisely to disrupt that culture of decline in attendance and belief.”

Traynor said the missionary effort will be based largely on work at the local congregational level in order to show support and take advice from Catholics who know what their communities and individual churches need to thrive.

The Catholic Church for centuries relied on generational support in which parents attended church with their children, who then attended church with their children and so on, he said. But that process has been disrupted by foundational changes in society in which people are less interested in and attuned to the tenets of Christianity, Traynor said.

“We are in not just a generational change but a change of epochs, from Christian to a newly resecularized culture … in Western civilization,” he said. “Forty to 50 years ago, the Catholic parish was really the center of community activities, in that families had their entire social network organized through the parish, and that’s just not true today.”

Looking for innovation: ‘It is not occurring naturally’

Traynor said his role is to learn what existing and potential Catholics want in a church, and to seek out new, innovative ways of connecting people to the church and to God.

“People are drifting along with the mainstream culture today. They’re going to tend to go further and further away from the church,” he said. “If parents desire to pass on their faith to their children and their children’s children, it takes a very focused, intense and sustained effort to make headway because it is not occurring naturally. It’s not enough to just have a church building and expect that people will show up.”

In South Dakota, about 30% to 40% of people who identify as Catholic attend mass weekly, which is 10% to 15% higher than the rest of the country but still not a number to be celebrated, Traynor said.

One goal of the church’s new missionary efforts will be to encourage churchgoers to share their passion for God and Scripture with Catholics who have stopped attending in order for them to return to the church.

The Catholic Church in the United States last year launched a three-year growth effort called the Eucharistic Revival, which is aimed at renewing the church through personal encounters with Jesus. The program invites creative initiatives first at the diocesan level, then at the parish level, finally culminating in a National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis in July 2024.

The Sioux Falls Diocese has gathered data on births, first communions, confirmations and marriages within the church and is comparing it to demographic data to look for places where the church might be weak or strong, and then adapt missionary strategies accordingly.

When it comes to the sexual-abuse scandal and cover-ups that have rocked the worldwide Catholic Church, Traynor said the church has embarked on a major effort to enact safeguards that will prevent such abuse in the future.

“The church has become a very proactive and exemplary leader in creating safeguards for children and vulnerable adults,” Traynor said. “The church can never do too much to ensure the safety of children, so I would never say the church has done enough. But I would also say that in the world today, the Catholic Church or school or parish is probably the safest environment of any public organization for any child.”

And yet, Traynor acknowledges that the stain of abuse may not have yet been cleared in the minds of many Americans, and that it may have led in part to reduced Catholic Church membership and attendance.

“We’re very focused and aware of this problem,” he said. “There’s been a rupture of trust. And the best thing you can do to evangelize or help them take another step closer to Jesus and the church is just to be a good human being to them and show that you are there to serve people’s real needs.

“The Catholic Church has a rich tradition of feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, caring for the sick, educating people and giving them health care, and visiting the imprisoned and marginalized.”

Priest and pastor shortage is another concern

Some religions, the Catholic and Lutheran churches among them, are also seeing a decline in the number of new priests and pastors who can run churches. The shortage is more acute in rural areas but is not a major factor in South Dakota declines, church leaders said.

And yet, recruitment of new leaders and church employees overall is an ongoing part of efforts to stabilize religious organizations. Hagmaier said the ELCA in South Dakota offers new employees who move to the state an incentive in which the church pays off their student loans.

But finding pastors to commit to churches in sparsely populated rural areas remains a challenge, she said.

Working as a pastor provides solid if not spectacular pay and benefits, Hagmaier said. Starting pastors receive a salary and benefit package ranging from $40,000 to $60,000 a year in value.

Rural positions become less attractive if pastors have to worry about the viability of a small-town congregation, she said.

“If your rural area is emptying out, with just a few people there, it’s hard to support a pastor’s salary, and if there’s nothing left for ministry, that’s a concern,” Hagmaier said.

The church will look different from before

Hagmaier said 75% of the ELCA congregations in South Dakota are considered rural, which creates challenges in filling open pastor positions or meeting unique needs of rural residents who want to attend church.

That problem led the synod recently to create the new rural liaison position to work with small communities, to keep the local Lutheran church viable and to learn what residents want and need from their church.

In communities where the church doesn’t have a pastor or faces some other type of uncertainty, the liaison visits the town for two weeks to talk to church members and others in the community to stabilize the church and also find solutions to local problems, Hagmaier said.

In Edgemont, where there is no pastor, the rural liaison stepped in to aid in the burial of a church member and provide support to the community after the death.

The new approach to strengthening rural congregations, which Hagmaier refers to as “presence and accompaniment,” is an example of how the Lutheran church is trying to respond to declining church membership and attendance in a collaborative rather than heavy-handed way.

“I don’t even like my kids to tell me what to do, so why would I want a bishop to tell me or my community what to do?” she said.

Hagmaier remains optimistic that with some innovation and new focus on listening and adapting to the needs of rural communities, the Lutheran church can continue to thrive in South Dakota.

“I’m very excited about the future of the church and rural ministry, but it most certainly will look different than it did before,” she said.

Young pastor takes positive approach

Zach Kingery is a Kansas native in his thirties who is pastor of two United Methodist churches in Jerauld County in east-central South Dakota.

Throughout his tenure as pastor, Kingery has been aware of the declining church membership and attendance across the country, but he has taken numerous steps to grow his congregations in Alpena and Wessington Springs.

“Going to church just for the sake of to going to church, that cultural obligation to go to church isn’t present anymore,” Kingery said. “There is a cultural decline in attending church. And it’s easier to walk away from church when it’s seen just as an institution, something we’re just supposed to do when it doesn’t really fit into your daily life and there’s no connection with it.”

Kingery said he has tried to create an atmosphere of positivity and encouragement in his congregations. He has developed close personal relationships with churchgoers, adapted sermons to be relevant to the small-town, rural congregations he serves and has taken the approach that Sunday sermons are a chance to put people on a path to living and spreading the word and ways of God after church services end.

“There is an increase in attendance at a life-giving church, those that are very present in their community, and very active. We’re trying to shift the narrative from a church you just go to once a week to being a place you come to that encourages you for the week ahead,” he said.

Kingery said he knows that people come to church in part to feel more upbeat and more supported in their lives, even in times of pain or sorrow, and also to gain insight into the word of God that can help them live better, more complete lives.

“Church isn’t a place for condemnation but is a place for conviction and encouragement,” he said. “If I stand up and tell you you’re a sinner and scream at you, you’re not going to be encouraged to change your life.”

Instead, Kingery uses Scripture as a conduit to share the word of God in a way that encourages church members to think deeply about problems and challenges in their lives, and to find a path toward improvement. And, he said, he asks them to share their positive religious experiences and belief in God with others, which can hopefully lead to greater church membership and attendance.

Deeper connections instead of pizza and games

At the roughly 240 Methodist churches in South Dakota and North Dakota, the average weekly attendance is about 40 people, Kingery said. Even in two towns with small populations, he has seen an increase in attendance during his six years as pastor, to about 45 people a week in Alpena and 65 to 70 each week in Wessington Springs. At Christmas and Easter services, he sometimes counts more than 200 people in attendance.

Kingery said he was encouraged to confirm 13 youths into the Methodist church in Alpena and another seven in Wessington Springs recently.

In order for churches to thrive and grow attendance long-term, Kingery said, church leaders must do more to engage with youth and make religion a larger, more integral and valued part of their lives.

“There was this movement that if we serve pizza and play games, that young people will come to church. Then they get older,” he said.

Instead, Kingery said he invests his time and energy in creating deeper, most honest connections with youth in order to show them the power of God but also to provide an opportunity to listen and work through the difficult questions young people have about their lives and the world around them.

“The teenagers I’m seeing be more invested in church are asking important questions and I’m doing my best to give them answers, even if sometimes the answer is that I don’t know,” Kingery said. “The ones that are responding the most are those who are finding connections and community through church. They ask hard, tough questions, and when you work with them through it and try to find answers together, then they want to be there.”

‘Being the church outside of these doors’

Like a lot of pastors, Kingery offers his sermons through online video platforms such as YouTube and on Facebook, a practice he started during the pandemic. The online sermons allow people to hear his preaching even if they cannot attend in person. And it enables former church members who have moved to tune in from other states or from outside his pastoral area in South Dakota.

Kingery said increasing church participation and attendance — and a stronger connection to God — will require pastors and other leaders to be more mindful of what people are seeking in their lives and to deliver important messages in a way that inspires and encourages others to join.

“That’s what the churches are kind of catching onto. Are we inviting people to church, am I being the church outside of these doors, how am I connecting with God during the week and connecting with others?” Kingery asks himself. “It has become more of an inviting process where other people in the community are catching on and being involved.”