At a time when they are needed most, South Dakota is facing a shortage of nurses that healthcare professionals worry could negatively affect patient care at hospitals across the state.

The nursing shortage has been ongoing for years but worsened during the pandemic.

High stress, long hours and fear of infection during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic caused more nurses than usual to leave the field, move to other states or retire early.

From 2015 to 2016, about 1,700 registered nurses left the South Dakota healthcare workforce. Last year, more than 2,500 nurses dropped out of the state workforce. One national nursing organization estimates that South Dakota will be almost 2,000 nurses short of the need by the end of the decade.

“The pandemic just kind of burned them out,” said Michelle Bruns, acting chairperson for the nursing program at Oglala Lakota College. “It’s a tough situation.”

The state higher-education system has not produced enough nursing graduates to keep up with a growing population and rising demand for healthcare services, and educators are scrambling to find ways to lure more students and produce degrees more quickly.

Meanwhile, a shortage of nurses in other states has raised competition to attract new graduates and experienced providers, but South Dakota healthcare systems are at a competitive disadvantage because median pay for nurses in South Dakota is the lowest in the nation, according to federal labor data.

The recent shortage has compounded a long-range lack of nurses in South Dakota, and some healthcare officials are growing concerned that patient care in the state could suffer, especially if the highly transmissible COVID-19 delta variant causes infections and hospitalizations to spike.

“Throughout South Dakota, and the U.S., this pandemic has shown the world how important health is,” said Nicole Kerkenbush, chief nursing and performance officer for Monument Health in Rapid City. “You need that workforce to help folks dealing with any type of healthcare crisis, whether it’s COVID or something else.”

South Dakota is ranked seventh in the nation for the greatest need of nurses, according to RegisteredNursing.org. The state ranks last in the nation in nursing pay with a median of $55,660, according to 2017 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics.

The aging of the nursing workforce is likely to exacerbate the need for nurses in the future. Nurses over the age of 50 make up 35% of the state nursing workforce.

The biggest need now is for experienced nurses in critical settings.

Monument Health is offering a $40,000 sign-on bonus for highly skilled positions in intensive care and operating rooms, said Kerkenbush. Billboards and ads for the eye-catching hiring bonus are in the Black Hills area and a few other states across the country, such as Maine, Connecticut and Mississippi, she said.

“Those are two specialty areas in very short supply throughout the country,” she said. “If someone needs a complex procedure and we can’t do it because of staffing, that is not a position we want to be in at all. We want those folks to be able to get the care that they need.”

The rate of registered nurses joining the workforce in the state has been decreasing for the last five years. Over the same time period, more have been leaving the workforce, according to the 2021 South Dakota Nursing Workforce survey report.

“We have known that there are various influences on the supply of nurses that are not new. We think about increasing healthcare needs coupled with baby boomers retiring, that’s a conversation that’s been around a long time,” said Kelly Hefti, Sanford vice president of nursing and clinical services in Sioux Falls.

While the overall number of registered nurses in South Dakota increased slightly in recent years — from 17,693 In 2016 to 18,693 in 2020 — the supply of workers has not kept up with the increased demand. In 2016, more than 1,600 positions were added to the workforce, compared to just about 200 between 2019 and 2020.

According to the report, the state saw a net loss of 478 licensed practical nurses between 2018 and 2020. Those who leftin 2020 reported retirement, exiting the profession, leaving South Dakota and inactivation of license as primary reasons for the decrease.

Rural areas have had greater difficulty recruiting nurses.

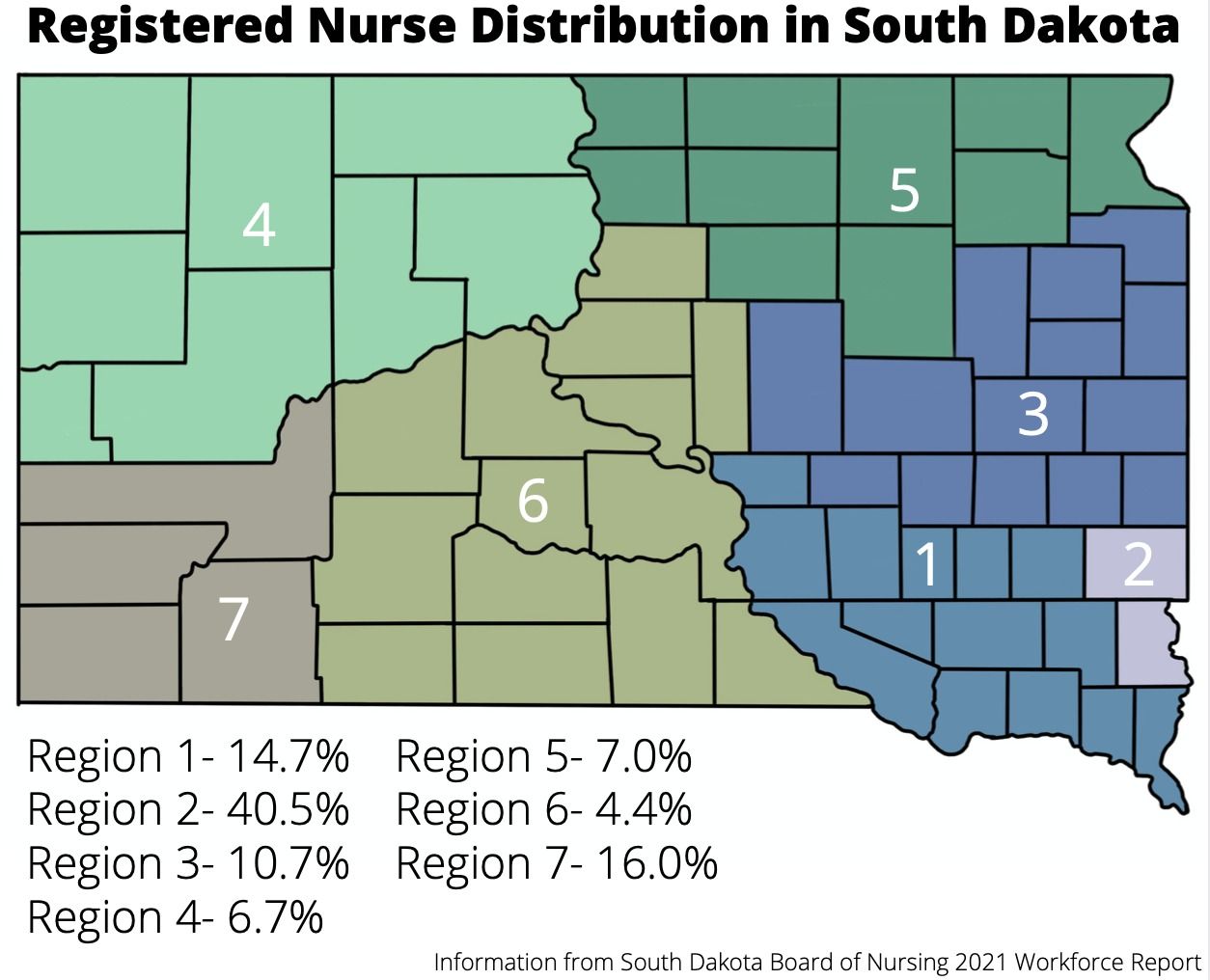

According to the South Dakota Board of Nursing 2021 report, though 28% of the state’s population live in Minnehaha and Lincoln Counties, almost half of the state’s registered nurses are in those areas.

More patients are coming from surrounding rural counties, adding to the need for nurses in the region.

To address the shortage, Kerkenbush said she spends her days focusing on ways to support staff, increase efficiency and use technology to their benefit.

During the height of the pandemic last fall, Sanford brought in traveling nurses to Sioux Falls hospitals to fill staffing gaps, a practice that is not in the norm, Hefti said.

“Late last fall, we did bring in traveling nurses during the peak of our COVID surge – we balanced our increasing adult volumes with the need to give our own nurses a reprieve,” Hefti said.

Due to recent inpatient admissions, because of COVID-19 and other conditions, Sanford is again using traveling nurses, Hefti said.

As far as day-to-day operations, Sanford approaches staffing based on the needs of their patient population and the skill mix of the nursing staff while also using unlicensed positions such as nursing assistants, Hefti said.

That challenge and the need for more nurses has been around for years in South Dakota.

“I’ve been in nursing for just about 30 years, and through that entire time, there hasn’t been a period where we haven’t been talking about a nursing shortage,” said Kerkenbush, who was a nurse in the Army for about 25 years before starting at Monument.

Both Hefti and Kerkenbush said that creating competitive employment packages and making education more accessible are ways the state can address the shortage.

Hefti said that offering 401K retirement packages, paid time off and staffing flexibility are a few ways Sanford tries to provide a competitive package.

Some of the state’s nursing programs are working to bolster the workforce by keeping the education modern and on the cutting edge of the latest techniques.

South Dakota State University’s Nursing program is designed to prepare future nurses for the modern workforce, said Mary Anne Krogh, Dean of the College of Nursing at SDSU.

“Students have to have a broad understanding of nursing care to pass their nursing boards,” Krogh said. “We do have a couple of programs for students to get rural clinical opportunities.”

Changes to nursing programs are happening to meet the workforce needs in South Dakota.

In August, the South Dakota Board of Regents approved a plan for SDSU to expand its Rapid City nursing program, while phasing out a program from the University of South Dakota, thereby increasing attendance in the SDSU program from 48 to 72 students.

“I hope that we make a big difference in the nursing workforce, particularly in western South Dakota,” Krogh said.

The South Dakota Board of Regents also approved this year a nurse anesthetists’ program at the University of South Dakota, addressing a need in a growing field.

Augustana University’s accelerated nursing program allows people who have graduated with any bachelor’s degree to become a nurse in 16 months, said program director and longtime nurse Lynn White.

Depending on the degree, a student may have to take some anatomy or physiology prerequisites. The program is attractive to those who don’t want to attend a four-year degree program again, and most graduates stay in the area, said White.

The same is true for the state’s public universities. In 2019, South Dakota’s public universities graduated 520 nursing students, 64% of whom are employed in South Dakota, according to data from the South Dakota Board of Regents. Students from South Dakota who graduated in 2019 experienced 78% in-state employment after graduation, and 31% of out-of-state students stayed after graduation.

Internships and residencies are a major part of a nursing students’ education. While getting real experience as a nurse, students are also getting a feel for the culture and environments of South Dakota health providers which can lead to post graduation employment.

Though some nurses left the field during the stress of the COVID-19, the pandemic has also raised Interest in the nursing profession among some prospective healthcare workers, Krogh said. Technology played a major role in keeping nursing students on track during the pandemic.

Kerkenbush said she also noticed more young people becoming interested in the healthcare field when the pandemic exposed the need for health workers. Getting the younger generation interested in nursing will be critical to the future of the profession.

“We certainly need our young folks and those looking for career changes to consider that option, which is a critical workforce to our communities’ health,” Kerkenbush said.

— News Watch reporter Danielle Ferguson contributed to this report.