Questions about the ownership of a strip of land within the Sioux Steel Co. site in downtown Sioux Falls has created a new, unexpected hurdle for the proposed $185 million redevelopment of the property.

The land in question was once a channel of the Big Sioux River and has ownership origins that stretch back beyond South Dakota statehood all the way to the presidency of Abraham Lincoln.

Archived press clippings appear to indicate that the channel that separated Seney Island from the western bank of the Big Sioux River was filled in and, along with the former island, was turned into usable land in the early 1900s. Sioux Steel Co. has owned and operated on the site since 1918.

Officials in the state School and Public Lands and Attorney General’s offices are reviewing maps, historic documents and other information to determine whether the state may have a claim of ownership to the strip of land.

Though it is uncertain what action, if any, the state might take if it claims to own the land, the state could demand financial compensation for its use, potentially adding to the cost of the redevelopment project. Theoretically, if deemed the owner of the land, the state could stand in the way of the redevelopment of the property.

A team of experts with the Lloyd Cos., which was selected by Sioux Steel ownership to redevelop the site, has completed its own investigation that the firm says indicates the land is not state-owned and is available for legal sale and development.

Jake Quasney, executive vice president of development at the Sioux Falls-based Lloyd Cos., said part of the channel route is within the roughly 11-acre site that Lloyd hopes to redevelop. Lloyd wants to turn the site on Sixth Street in Sioux Falls into an urban community with riverfront hotel and convention center, residential tower, parking ramp and an office and retail complex on the north end of downtown Sioux Falls.

According to South Dakota law, the state can claim ownership of any land beneath a waterway that is now or ever has been navigable. The key question state officials are investigating is whether the former channel was navigable.

Quasney said Lloyd and Sioux Steel are confident that their research proves the channel was not navigable and should not be considered state land.

“From our title perspective, and we have a lot of the history that exists there, from our perspective it pretty well supports that the land is available to us,” Quasney said. The uncertainty over the land ownership has arisen at a critical time for the project, he said.

In January, Lloyd Cos. received approval of a Tax-Increment Financing district from the city of Sioux Falls that will provide the firm with $21.5 million in tax benefits. The company said after the TIF approval that construction on the project could begin as early as August 2020. Project timelines call for full completion in spring 2022.

“We’re at a weird point here if this was to cause everything to go south,” Quasney said of the project, adding that Lloyd had already spent $3.5 million on planning. “For a family [the Rysdons] that has operated a business for 100 years, they stand to lose something. But we’re also talking millions of dollars here that this could cause an issue with.”

Amy L. Ellis, a legal representative for Sioux Steel, said the sale of land to Lloyd would occur before any development would take place. She said the steel company, which is moving its operations to Lennox, S.D., is confident it owns the channel land free and clear.

“Sioux Steel has operated on the property for over 100 years and acquired the property after it was filled in,” Ellis wrote to News Watch in an email. “We believe that title properly rests with Sioux Steel and can be conveyed to Lloyd Companies for the project.”

Ellis said the location of the channel land is not precisely known but that it appears to wind through the southern and northern edges of the redevelopment site.

The land-ownership questions were initially raised by Steve Wegman of Pierre, a former state policy analyst who now runs the South Dakota Renewable Energy Association.

Wegman said he first heard about the mystery of the former island and channel when he was a paperboy for the Sioux Falls Argus Leader and a customer on his route told him about it.

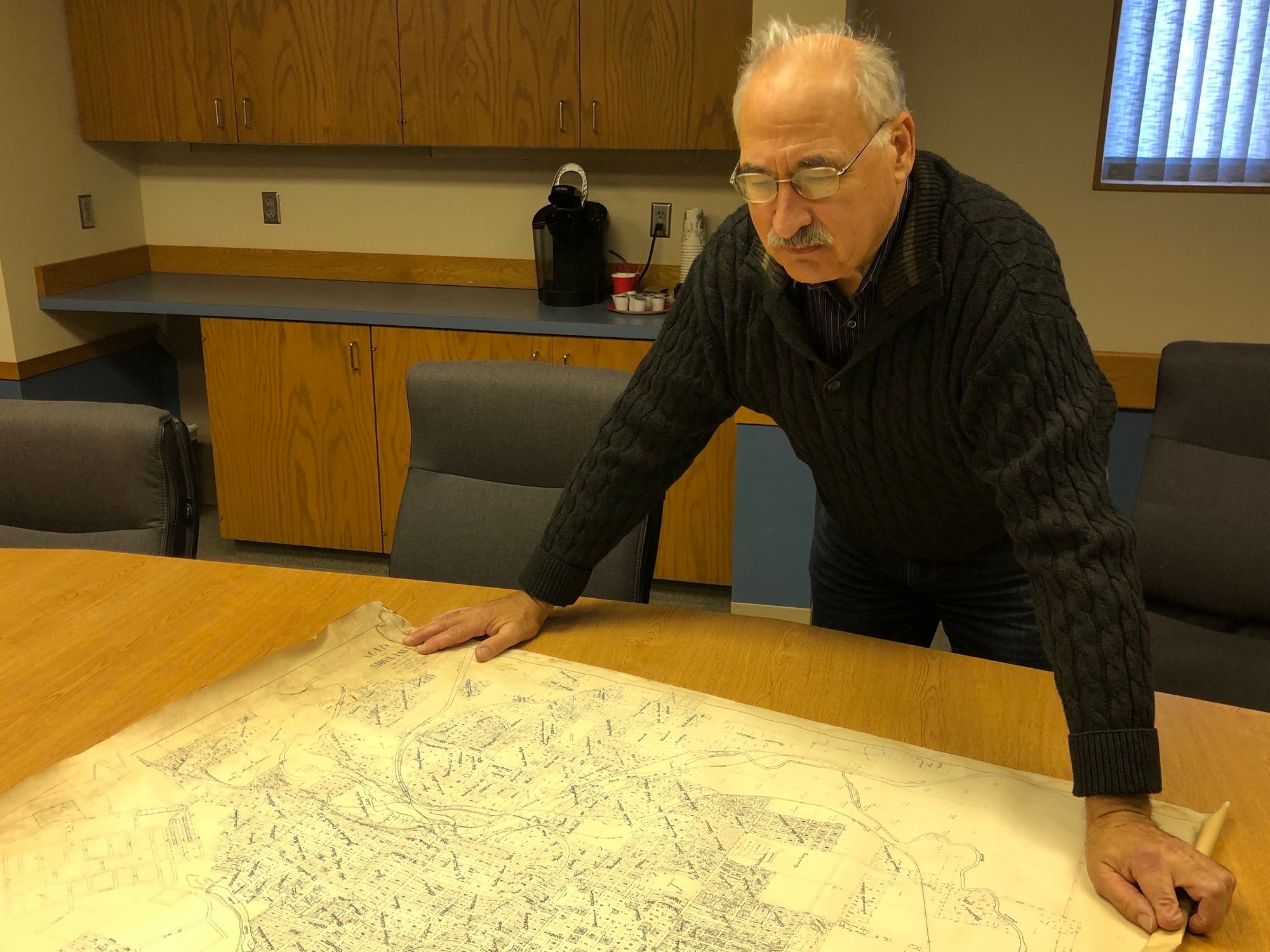

Decades later, when the Sioux Steel redevelopment project first made news in 2018, Wegman — a trained surveyor who is also an amateur historian — said he began researching the history and ownership of the island and channel.

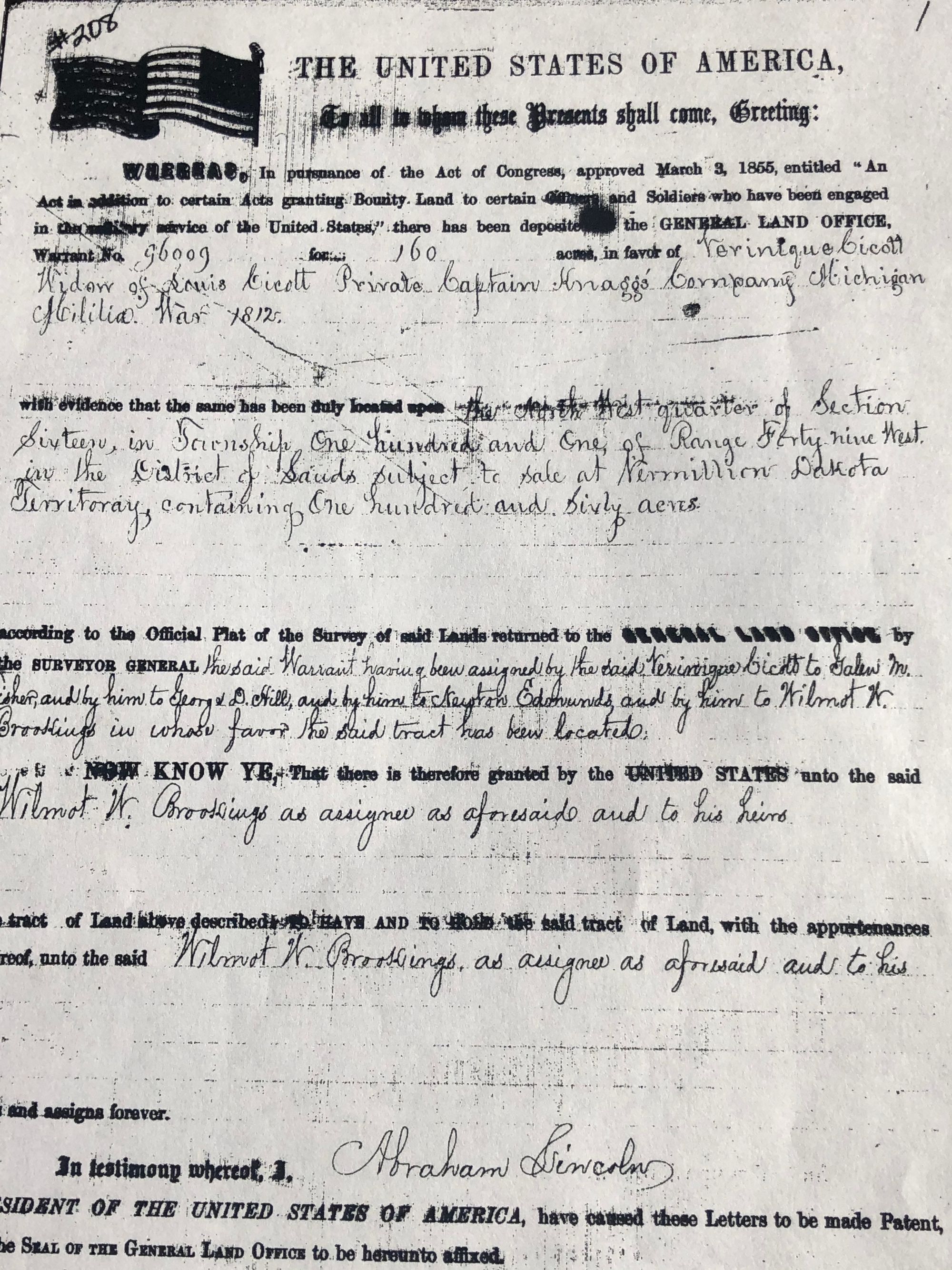

His research took him back to the original land warrant, which showed that 160 acres was given by the U.S. Congress to Verinique Bicott, the widow of Louis Bicott, who was under the command of a Capt. Knagg in Michigan when he was killed in the War of 1812.

A federal document later shows that after changing hands a few times, the land was formally deeded by President Abraham Lincoln in 1863 to Wilmot W. Brookings, who served as provisional governor of the Dakota Territories and later as a South Dakota Supreme Court justice (and who is the namesake of both Wilmot and Brookings, S.D.)

Wegman said his research raised questions about who owned the island and also who filled in the western channel. He said his findings appeared to indicate that the ownership of the island and channel land was unclear but is probably held by the state.

“It’s an interesting story all around,” Wegman said. “But the bottom line is that somebody does not have clear ownership of that property.”

Wegman said he has a long-held belief that the state has been too quick to give away its land, particularly highly valuable land. The state also has lost out on opportunities to preserve valuable land, he said.

In late 2019, Wegman took his findings to Ryan Brunner, commissioner of the state School and Public Lands. Brunner said he began his own research in February and that he eventually reached out to Lloyd Cos. to inform them the land ownership was in question.

For a time, it appeared possible the state could also make a claim of ownership to the former island, which is also now part of the Sioux Steel property.

But Brunner said the state’s research showed the island property is not subject to state ownership.

Brunner said state lawyers had concluded that the estimated 18- to 20-acre island parcel is legally owned by Sioux Steel and can be sold and redeveloped without title concern.

According to statute 5-2-4, the state relinquishes ownership of islands or sand bars in waterways if the land is “conveyed” or given by the state or federal government to a private party.

In this case, since the federal government deeded the full 160 acres of Bicott land to Wilmot W. Brookings in 1863, the state’s current position is that it was conveyed to Brookings and is therefore no longer state land.

“The state has never been the owner of that land,” Brunner said. “I have notified Lloyd Companies that the island is not owned by the state.”

Yet the historic and modern status of the former channel is less clear, Brunner said.

In general, state law 43-17-3 says that waterways that are navigable, or were at some point, remain state owned even if they fill in naturally or by outside means.

“Islands and accumulations of lands formed in the beds of streams which are navigable and in meandered lakes belong to the state, if there is no title or prescription to the contrary,” the law says.

That puts great importance on whether the channel was navigable before being filled in.

Brunner said Lloyd had provided the state with “an extensive report and engineering opinion” that appears to show the western channel was not navigable and therefore is not state land.

But the state has not yet made its determination on the ownership of the channel lands — either whether they were navigable or whether the state will claim ownership, Brunner said.

A team of legal and engineering experts in the state Attorney General’s Office is reviewing the Lloyd report and is doing its own research. Brunner said the state’s opinion on the channel ownership could be released within the next few weeks.

Brunner refused to take a position on whether the channel is state-owned, but he said it is incumbent on the state to do the research to make a fair ruling.

“We are having experts review it because we are trying to get more assurances tied to the possibilities there; we’re doing our due diligence because there’s a lot of different factors at play,” Brunner said.

Quasney said in an email to News Watch that the firm’s experts had found published materials indicating that before being filled in (possibly by a railroad company or Sioux Falls Light and Power), the western channel was filled with stagnant water and would flow only during flooding events.

“The reality was that the area was likely surrounded by stagnant water, and was an area that largely housed vagrants,” Quasney wrote. “A number of pictures are seen where people are taking horses and buggies across the low lying area where stagnant water would sit and where water would run during flood stage waters.”

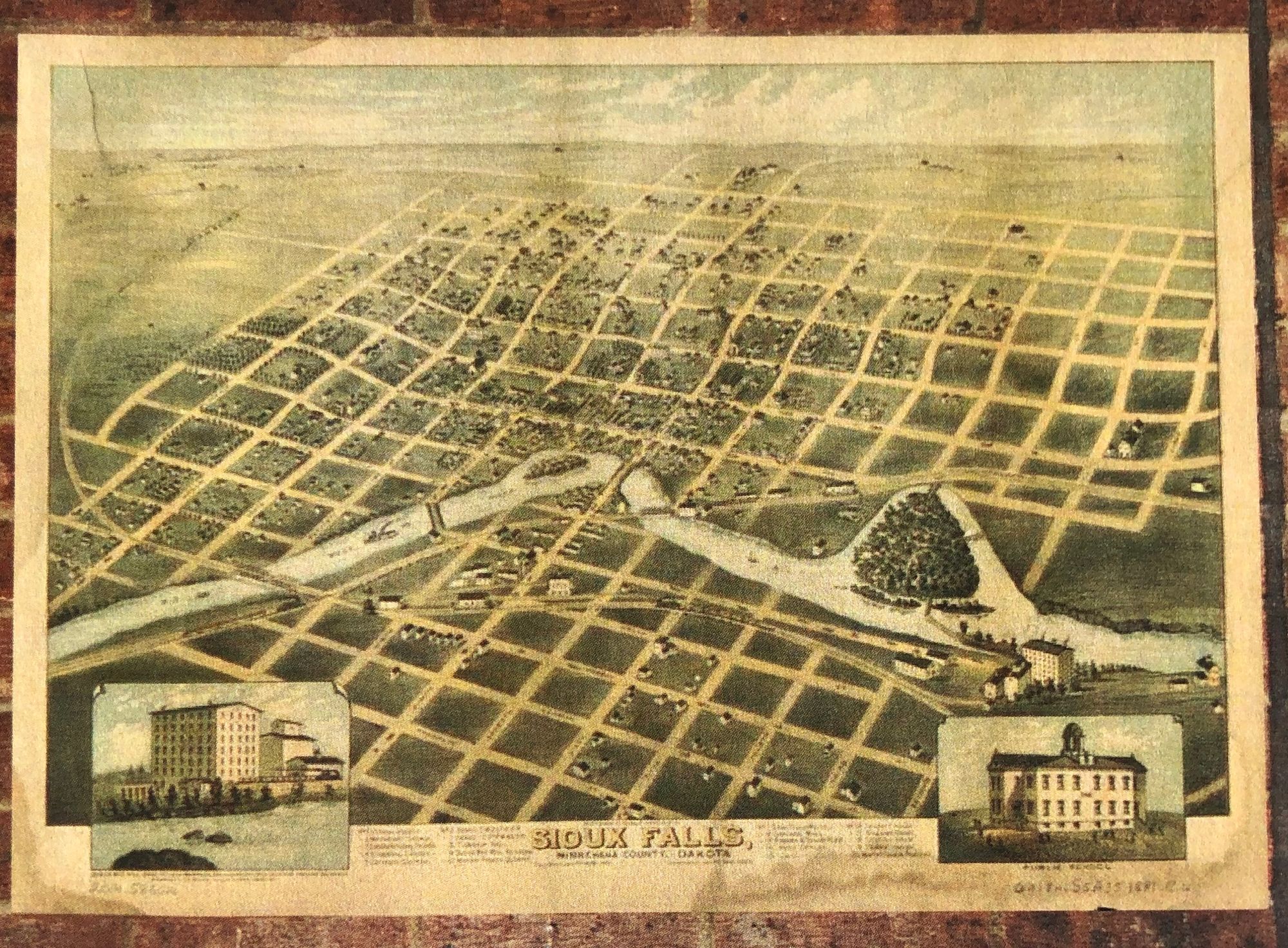

However, some old maps of the island and river channels surrounding it appear to show a fairly large river opening to the west of the island. In maps from 1859 and 1881 discovered by Wegman, the cartographers both drew eastern and western channels of roughly equal width around the island, and one map even shows the western channel as wider than the eastern channel.

A 2016 Argus Leader article by historian Eric Renshaw noted that Seney Island, also known as Picnic Island and Brookings Island, was a popular destination for revelers in the late 1800s but devolved into “a dumping ground for garbage” in the early 1900s.

Renshaw wrote that the island was separated from the shore by “a shallow channel of water on its western side that needed to be forded” to reach the island.

The importance and sensitivity of the state’s ruling and the fact that it could affect a major redevelopment plan in the state’s largest city is not lost on the state, Brunner said.

“It’s a very large project we’re talking about, and there’s a lot that goes into that,” he said.

The office of School and Public Lands is responsible for managing and renting state-owned lands that were given to South Dakota by the federal government at statehood in 1889. The lands are mainly rented by farmers and ranchers, who pay about $15 million in leasing fees to the state each year. Most of that revenue is used to fund K-12 and higher education in the state, Brunner said.

While other, energy-rich Great Plains states often face land-ownership questions surrounding navigable or meandering waterways arising from mining interests, South Dakota rarely faces those issues.

The Sioux Steel case has led him to do research and to learn more about South Dakota laws.

For example, Brunner pointed out that when heavy rains cause a navigable waterway to change course, the state maintains ownership of the new river or stream bed but ownership of the newly dried portion is transferred to the landowner who lost land when the waterway changed course.

State residents depend on his office to review the ownership of land and, if it is state-owned, possibly to receive compensation for future use, he said.

“As a public entity, we need to do that due diligence,” Brunner said. “Once the information comes back, then we will have to review other caveats about meandering waters and changes that have taken place since the 1880s.”