Nestled in the silt, sand or fine gravel of South Dakota’s rivers and streams live some of the state’s least appreciated yet most ecologically important creatures — freshwater mussels.

Their names spark the imagination: Fatmucket, White Heelsplitter, Higgins Eye, Round Pigtoe, Giant Floater, Plain Pocketbook, Fawnsfoot.

Usually hidden beneath the water’s surface, mussels do the quiet work of filtering water in South Dakota’s rivers and streams, helping other aquatic species such as fish thrive. They are a natural food source for otters, ducks, herons and fish.

Many species of these critical members of freshwater ecosystems may be vanishing within South Dakota. Recent surveys of the state’s 14 major river basins — comprising the first comprehensive assessment of living mussel species and their population sizes in South Dakota rivers and streams — found only 17 of the 36 species once known to live in state waters, a 53% decline.

The decline of freshwater mussel populations in waterways in South Dakota and across North America is a major concern on several environmental levels.

Freshwater mussels are powerful filter feeders, consuming phytoplankton, algae and even bacteria from rivers and streams while also filtering out particles at rates measured in gallons per day. At least one mussel species can clear lake water of significant amounts of E. coli, a bacteria that can cause serious illness in humans. Research continues into their promising abilities to ‘treat’ manmade contaminants.

Mussels have not been studied as intensively as other animal groups and much remains to be known about them. “Despite uncertainty about the precise value of freshwater mussels, it is clear that they have substantial value to humans, possible many millions of dollars in individual ecosystems, which should be taken into account in environmental decision making,” wrote David L. Strayer, a freshwater ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in his article, “What are freshwater mussels worth?”

Experts say the reduction in mussel populations in South Dakota waterways is further evidence of largely poor water quality in a state where 78% of South Dakota stream-miles and 85% of lake acres are considered “impaired” in some way.

Harm to mussels done by humans

Freshwater mussels have been on the decline for two centuries — all for reasons related to the actions of man.

In the late 1800s and for several decades, mussels were harvested for their pearls and shells from South Dakota waters, including the James and Big Sioux rivers. Tuscan, located four miles southwest of Menno, was a center of mussel harvesting, according to a 2009 article in South Dakota Magazine.

Mussels were boiled to open their shells and remove the meat. While some people ate the mussel meat, often it was fed to pigs, or used as catfish bait if rotten. Boxcars filled with tons of shells were shipped by rail to Iowa factories to be made into iridescent buttons. Plastic replaced shell for buttons in the 1950s.

South Dakota’s mussel populations have yet to recover from that decimation.

After over-harvesting came land-use changes that altered water quality and stream bed stability, further harming mussel populations.

Accelerating land-use changes — often tied to expansion of agriculture — lead to soil runoff, sedimentation and non-point pollution from manure, fertilizer and pesticides. Water clouded with clay, silt and other particles, including algae, can affect the fish hosts mussels rely on to reproduce. Increased sediment smothers mussels. Pesticides can poison them. Fertilizer runoff causes excessive algae growth that depletes oxygen.

Thirty-six percent of tested water in South Dakota rivers and streams has excessive amounts of total suspended solids, according to the 2020 South Dakota Integrated Report for Surface Water Quality Assessment prepared by the state. Suspended solids, which can include soil particles, can increase turbidity and water temperatures, decrease oxygen levels and generally degrade conditions for fish and other aquatic life.

“Similar to previous reporting periods, nonsupport for fishery/aquatic life uses was caused primarily by total suspended solids from agricultural non-point sources and natural origin,” the report states. “Non-point source pollution is the most serious and pervasive threat to the water quality of South Dakota’s waters.”

The South Dakota Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Department of Game, Fish and Parks have worked for decades with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, farmers, ranchers and other organizations to improve water quality in South Dakota’s rivers, streams, lakes and reservoirs.

Farming and ranching organizations say that their members are good stewards of the land on behalf of future generations, and that those who work the land are the “original environmentalists.” Many South Dakota landowners participate in conservation efforts, such as the reduction of sediment flowing from the Bad River basin into the Missouri River. But state data tell a story of high levels of agricultural pollution of surface waters.

“While substantial progress has been made toward reducing pollution from point sources such as wastewater and industrial plants after the passage and implementation of the [1972] Clean Water Act, non-point source pollution remains an entrenched problem. NPS pollution is unregulated as agricultural activities are exempt from most of the provisions of the Clean Water Act,” the state report says. As of 2019, 78% of assessed stream-miles were impaired. E. coli, a bacteria living in livestock and wildlife feces, and total suspended solids, which often include materials from soil erosion, were the contaminants in first and second places.

The DANR did not respond when asked in an email if the agency has specific numeric goals for reducing the percentage of impaired waters in South Dakota or reducing the percentage of total suspended solids within specific timeframes.

“The technical and financial assistance currently available is not sufficient to solve all NPS pollution issues in the state. Landowners need to understand the non-point source issues and how their activities contribute to NPS pollution. Educating the public about NPS pollution issues may prompt landowners to voluntarily implement activities that control NPS pollution. The continuation of existing activities coupled with the addition of innovative new programs may reduce non-point source pollution in South Dakota,” the state report says.

After poor water quality come physical barriers. Thousands of impoundments on tributaries restrict the natural volume and velocity of water that mussels need to reproduce. “Even dams as low as 1 meter in height have been found to inhibit the distribution of mussels as they can create unnatural sedimentation and flow regimes as well as cause barriers to fish host locality and movement, thus inhibiting the ability for successful mussel recruitment,” Faltys writes.

Perched culverts and other blockages to mussel larvae movement need to be adjusted so that mussel larvae and host fish can move beyond short stream segments. “It’s important to maintain that connectivity,” says Rich Biske, resilient waters director for the Nature Conservancy in South Dakota, North Dakota and Minnesota.

The increasing spread of invasive zebra mussels add to the threats to native mussels as the invaders move up South Dakota’s navigable waterways and into lakes. These non-native, proliferating mussels prefer attaching to live mussels over empty shells or stones. Many zebra mussels can team up to keep a single native mussel from opening up to feed or reproduce. In great numbers, they deplete the phytoplankton native mussels need for food.

Studies find evidence of clear declines

Measuring and cataloging the mussel population in South Dakota waterways was an arduous and time-consuming but critically important process that is necessary to understand where mussels exist and why they are dying off.

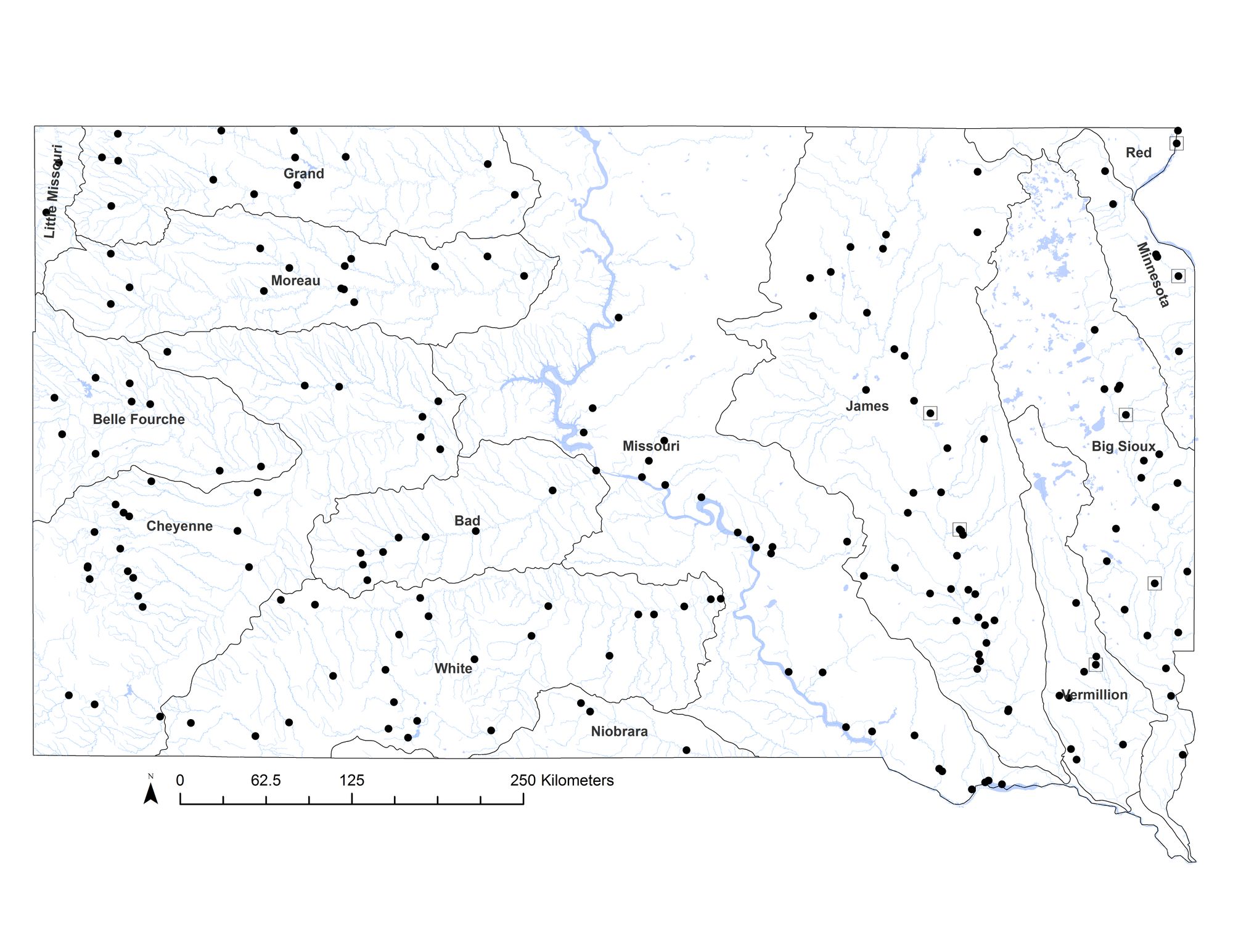

During 2014 and 2015, Kaylee Faltys and her research team waded in streams, feeling the muck for mussels with their bare hands at 202 sites within the 14 major river basins across the state. Faltys earned her master’s degree in biology at South Dakota State University by leading the first statewide assessment of mussel species and their populations.

Researchers did not wear gloves as they felt stream bottoms with their hands, reaching as deep as four inches into silt. “Snapping turtles definitely were a concern. At one of the sites we even had carp jumping out of the water at us,” Faltys said.

Besides, gloves would get in the way. “Once you feel a mussel, you know it’s a mussel. Whereas if you have gloves on, it could just be a rock.”

The more exciting scientific work started when they pulled mussels out of the water.

“When we did find mussels … we were pretty thrilled when we found them,” Faltys said, noting that mussels were found at only 44 of the 202 sites searched.

The work involved identifying the species, measuring the mussel’s dimensions, photographing it and returning the animal to its original location, right-side up. “We made sure not to put them upside-down or they’d suffocate,” she says. “We would actually go put them back in the sediment.”

When a mussel species was abundant in an area, an individual mussel could be selected for on-campus research. This mussel would be separated from its shell and preserved in ethanol.

Although they did not go to river or stream segments too deep to wade, the shallower waters where they looked were tributaries to those deep waters and reasonable places to search. Searching in deeper waters wouldn’t have provided additional species and would have required scuba diving equipment and multiple licenses, she says.

After visiting the 202 sites, Faltys produced a grim tally: only 15 species of 36 anticipated species were found, 11 as live specimens and four in the form of recently used whole or half-shells. Of the 202 survey sites, only 91 total sites had live or empty-shell evidence of mussels. No evidence of mussels was found at 111 of the sites, more than half.

A silver lining appeared later in 2016, when Faltys and her colleagues separately assessed population sizes at the 44 locations with living mussels. A live Spike mussel and a half-shell of the Ellipse mussel were discovered, the first time each species has been found in South Dakota. Two additional known native species also were found in 2016: a Plain Pocketbook and a Fawnsfoot, bringing the study total to 17 out of 36.

Faltys made a point in 2016 of surveying seven locations previously surveyed by other researchers between 1975 and 2005. She found a decline in the number of the mussel species at five sites. The number of species increased at the sixth site and stayed the same at the seventh.

Faltys also found a decline of overall species richness or diversity. About 63% of the mussels found in the statewide survey were Giant Floaters and 10% were White Heelsplitters. Both species have glochidia, or baby mussels, that can survive in impounded waters and attach to any fish. This indicated that other species with more specific habitat requirements and fish hosts may be severely reduced in numbers or have vanished from South Dakota.

“This stark decline in species richness may suggest that habitat conditions in South Dakotan streams and rivers are degrading, possibly due to a variety of factors such as land-use changes, impoundments, habitat destruction and host fish availability,” she said.

A 2019 study by Katherine Wollman, an SDSU master’s student in wildlife and fisheries science, checked freshwater mussel populations in 116 East River lakes and reservoirs, finding just seven native species and two invasive ones, the zebra mussel and Asian clam.

Like Faltys’ study of rivers and streams, the predominant species at 76% of specimens found,was the widely adaptable Giant Floater.

“They’re hardy,” Faltys says of Giant Floaters. “They’re the most generalist species you’ll find. We’d find those in some of the nastiest streams. You would never imagine mussels would be in there. They just live anywhere, thankfully.”

Faltys’ and Wollman’s studies were funded by the Game, Fish and Parks Department and the South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also helped fund Faltys’ study.

Freshwater mussels species vulnerable to decline

Freshwater mussels (Latin name Bivalvia: Unionidae) are ancient creatures, believed to have originated in East and Southeast Asia during the Jurassic period and to have expanded into North America in the Cretaceous, when dinosaurs still roamed the continent.

While saltwater mussels are considered a seafood delicacy, freshwater mussels are not so tasty. One critic has compared their flavor to dirt.

Scientists think the ancestors of today’s mussels moved into freshwater rivers and streams created as the last glacier scoured eastern South Dakota 10,000 years ago, dragging mussels from warmer waters upstream. Glaciation gave us the diagonal form of today’s Missouri River, the James River basin, and our small lakes in the far northeastern part of the state. West River was not similarly glaciated, and freshwater mussel species are fewer.

The U.S. and Canada have the most diverse populations of freshwater mussel species in the world, with 301 total species, according to NatureServe Explorer, an online biodiversity database. But a January 2021 NatureServe analysis shows 63% of freshwater mussel species are vulnerable, imperiled or critically imperiled, second only to freshwater snails. In comparison, 40% of amphibian, 34% of freshwater and anadromous fish, 17% of mammal and 13% of bird species are at similar risk. As of January 2022, NatureServe listed 25 North American freshwater mussels as extinct, with eight declared gone from the earth by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service last October.

Freshwater mussels reproduce in complex ways, which in turn complicates their conservation. Because they anchor themselves in the substrate, they require a moving host and usually flowing water to genetically diversify and carry larvae away to new locations.

This is generally accomplished by a male mussel releasing sperm into moving water; these are taken up by a nearby female through an intake siphon. The female broods fertilized eggs in her gills until they mature to microscopic glochidia. Glochidia are released from her gills and must attach to the fins or gills of fish.

Some mussel species will settle for any fish, while others only reproduce with the help of a specific species. If glochidia attach to the wrong fish, that fish’s immune system kills the baby mussel. After glochidia hitch a ride on an appropriate fish, they stay attached for a few weeks to several months, then drop off. They must alight on suitable substrate to burrow and begin growing in their new homes. In the right location and conditions, some species of freshwater mussels can live for more than 100 years.

Conditions in North America hundreds of years ago were ideal for the creation of large and concentrated assemblages of mussels: adequate food, only natural sedimentation and relatively stable stream beds. Miles-long assemblages of multiple species of mussels were created, paving river bottoms like cobblestones. Their combined consumption of phytoplankton, algae, bacteria, fine and dissolved organic materials and compounds kept freshwater streams clear and contributed to a natural balance that benefitted fish and other aquatic species.

In South Dakota, the most diverse and abundant assemblages were and continue to be east of the Missouri River. Those conditions changed with the arrival of European settlers and the use of most of South Dakota’s land to cultivate row crops and raise livestock.

Extinction a real potential outcome

The Higgins Eye, Winged Mapleleaf and Scaleshell are native mussels listed as federally endangered, meaning they are endangered throughout the nation. None of these was found in Faltys’ surveys of South Dakota waterways. The Winged Mapleleaf and Mapleleaf are two distinct species.

The latest state GFP Wildlife Action Plan lists the Higgins Eye and Scaleshell as in need of conservation but not as threatened or endangered within state borders. The Creek Heelsplitter, Elktoe, Hickorynut, Mapleleaf, Pimpleback, Rock Pocketbook and Yellow Sandshell mussels also are listed by the state as in need of conservation.

The state list’s omission is puzzling. A study by Anthony Ricciardi and Joseph B. Rasmussen, published more than 20 years ago in Conservation Biology, stated that no other group of North American land, marine or freshwater animals is going extinct as fast as mussels.

“This [overall decline in freshwater fauna] is compelling evidence that North American freshwater biodiversity is diminishing as rapidly as that of some of the most stressed terrestrial ecosystems [tropical rainforests]. Although larger absolute numbers of species are at risk in the tropics, the elimination of even a few species in temperate habitats can promote further extinctions and disrupt ecosystem functioning,” the authors wrote.

The state Wildlife Action Plan does categorize eight of the nine mussels in need of conservation as “critically imperiled” and “especially vulnerable to extinction.” The ninth, Mapleleaf, is “imperiled because of rarity” and “very vulnerable to extinction.” Those categorizations mean South Dakota’s “conservation goal is to improve the species’ abundance and distribution,” the plan says.

Of these nine mussels, Faltys found only the Mapleleaf.

In contrast, the state lists five fish as endangered and four more as threatened. The endangered fish are the banded killfish, blacknose shiner, finescale dace, pallid sturgeon and sicklefin chub. The state-listed threatened fish are the longnose sucker, northern pearl dace, northern redbelly dace and sturgeon chub. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the pallid sturgeon and Topeka shiner as endangered, and the shovelnose sturgeon as threatened.

Of the state-listed endangered or threatened fish species, at least five inhabit clear streams that also are mussels’ natural habitat: the blacknose shiner, finescale dace, longnose sucker, northern pearl dace, and northern redbelly dace. Nine additional fish are listed as being between extremely rare or vulnerable to extinction and very rare, found abundantly in only some locations or vulnerable to extinction.

In the South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks Commission’s 2020 biennial review of the threatened and endangered species list, mussels are mentioned only once, under State Wildlife Grant Accomplishments, in a 2008 study that sampled Minnesota River tributaries in South Dakota for their compositions of fish, mussel and other aquatic invertebrate species, with an emphasis on identifying rare species.

Experts: more action needed to protect mussels

Since Faltys’ study was published, the state’s only specific action to protect freshwater mussels has been a 2020 state administrative rule that bans commercial and noncommercial harvesting of freshwater mussels. State regulations allow people to pick up empty mussel shells, but not those of endangered or threatened species.

Chelsey Pasbrig, a GFP aquatic biologist, said in an email that her agency is concerned about the decline of freshwater mussel populations in South Dakota, and it is aware they are among the most endangered animals in North America.

“GFP has begun collaborations with other states to explore the option for augmenting populations with propagated individuals; however, this is in its infancy” she wrote. “Kaylee Faltys’ study provided us a snapshot of the status of freshwater mussels in South Dakota; however, future research and monitoring is likely needed.”

Pasbrig added that no current mussel monitoring efforts are underway in South Dakota.

“Unfortunately, the professor at SDSU who could assist with this expertise is since retired, therefore future monitoring and research efforts have not continued at this time. There are endless questions that exist regarding the status of freshwater mussels in S.D. and across the country; however, limited resources both financially and staffing exist,” she wrote.

Since at least 1985, the GFP also has sponsored mussel research by a retired University of Sioux Falls faculty member and a retired departmental wildlife biologist, among others.

Pasbrig says the department currently addresses water quality issues that may be contributing to decreased mussel abundance and diversity through the Conservation Reserve Program, the James River and Big Sioux River Conservation Reserve Enhancement programs, the EPA 319 non-point source watershed projects and riparian buffer programs. The state agency also recently expanded its private lands habitat program and aquatic habitat program, which partner with landowners and other conservation entities to improve habitat, Pasbrig says.

GFP did not respond to follow-up questions asking for figures on the net numbers of additional landowners and acres in the expanded private lands habitat and aquatic habitat programs. A request for the number of stream miles of riparian buffers created in the last several years also was not answered, but previous reporting by News Watch has showed that state efforts to encourage implementation of agricultural buffer strips has been extremely slow to catch on.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declined to comment on its role in monitoring and protecting freshwater mussels in South Dakota at this time.

Faltys and others have called for further research and monitoring of freshwater mussel populations in South Dakota.

“Our research … suggests that the statewide unionid structure is changing quickly, thus adequate conservation strategies are needed for the future survival of this group,” Faltys said.

Biske, of the Nature Conservancy, agrees that “more can be done” in South Dakota to monitor and conserve existing freshwater mussel populations

But under the two major federal acts pertaining to water, the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, individual and groups of South Dakotans do not have the right to take legal action against ag-related nonpoint source polluters, says David Ganje an Aberdeen native who practices natural resource and commercial law in South Dakota.

However, when endangered species are involved, government entities have the right to intervene to protect the endangered species, although this is rarely done, he said.

Individual states do have the power to regulate non-point source pollution and protect wildlife, should their policymakers choose to do so. South Dakota law states that both South Dakota’s waters and wildlife are the property of all South Dakota residents.

Ganje points to Wisconsin as a state that manages non-point source pollution well, with a published 5-year, 110-page plan. Wisconsin’s approach results in better surface water quality, despite intensive farming and industrial activity. Its most recent report states that 83% of its waters are healthy, 13% are impaired and 4% are being restored. South Dakota’s corresponding numbers are almost reversed: 78% of stream-miles are impaired in some way, while only 22% are healthy. Lake acres are 85% impaired and only 9% healthy.

Wisconsin also has a strategy to reduce phosphorus and nitrogen pollution from fertilizer applications.

“If over time those parties in society [agricultural, manufacturing, construction industries] are put in the limelight, invited to meetings, having the DENR/DANR sit down with them and say ‘What can we do as a group? What should we do? These numbers are getting worse and worse and worse.’ You know, there might even be some press that shows up to some of those meetings. That’s how you change this stuff,” Ganje said.

The Nature Conservancy, which works to conserve 900,000 acres in South Dakota and the two neighboring states, is looking at how it can help streams in good condition stay that way by promoting soil-healthy agricultural practices such as no-till, reduced till, cover crops, buffer strips and adding rotations of small grains and hay to fields usually planted with corn or soybeans.

Faltys says options for conservation could include propagating young mussels of existing species and releasing them into streams with small populations, reintroducing species that once lived in certain streams, restoring mussel populations to historic levels and creating easements that would increase buffer zones to reduce sedimentation.

She identified the Big Sioux, James and Minnesota river basins as areas of high mussel diversity that would be optimal sites for mussel conservation. She recommends focusing on the Whetstone River in Roberts and Grant counties, Bios de Sioux River in Roberts County, Medary and Six Mile creeks in Brookings County, Split Rock Creek in Minnehaha County, Shue Creek in Beadle County, Lone Branch Creek in Hutchinson County, Cottonwood Creek in Jackson County and the James River in Hanson County.

Areas Faltys listed as high priorities overlap with South Dakota GFP Aquatic Conservation Opportunity Areas. These areas are diverse aquatic habitats, low in human-caused stressors and have some public ownership.

Standardized surveys of South Dakota freshwater mussel populations should be done, and the public needs to be educated about freshwater mussel conservation, Wollman said. “Expressing why we do not want invasive species, like zebra mussels, is important, but there is currently minimal effort expended to provide information regarding species we are trying to protect.”

One ray of hope for additional funding to protect wildlife in need of conservation is the bipartisan Recovering America’s Wildlife Act of 2021. Pasbrig calls it “a potential game changer for state and tribal wildlife agencies” that would help the agency implement portions of its Wildlife Action Plan for the state’s 104 species of greatest conservation need, including the nine freshwater mussel species.

But U.S. Sen. John Thune, R-South Dakota, expressed hesitation in 2018 about an earlier version of the law, saying he favors additional funding for wildlife preservation but wants to know more about where the money is coming from and where it will go. All three members of the state’s congressional delegation were called in January 2022 and asked for their positions on the recovering wildlife act. Staff members in the office of U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds and Rep. Dusty Johnson responded but did not provide official stances on the act.

“If conservation efforts keep going, I have hope,” Faltys says of mussels’ chances of avoiding extinction in South Dakota. “I think that South Dakota Game, Fish and Parks, they do have an awareness of this, and they do want to conserve the species there.”

What the Nature Conservancy advocates in South Dakota is to “ensure we don’t lose those populations that we have,” Biske said. “We can’t afford to lose any more.”