ST. FRANCIS, S.D. – When talk turns to preparing more children on the Rosebud Indian Reservation to pursue positive opportunities, Stacee Valandra just nods her head.

The 41-year-old Lakota educator grew up on the reservation in Todd County, one of the poorest sections of America, where more than 60% of residents under age 18 live below poverty level.

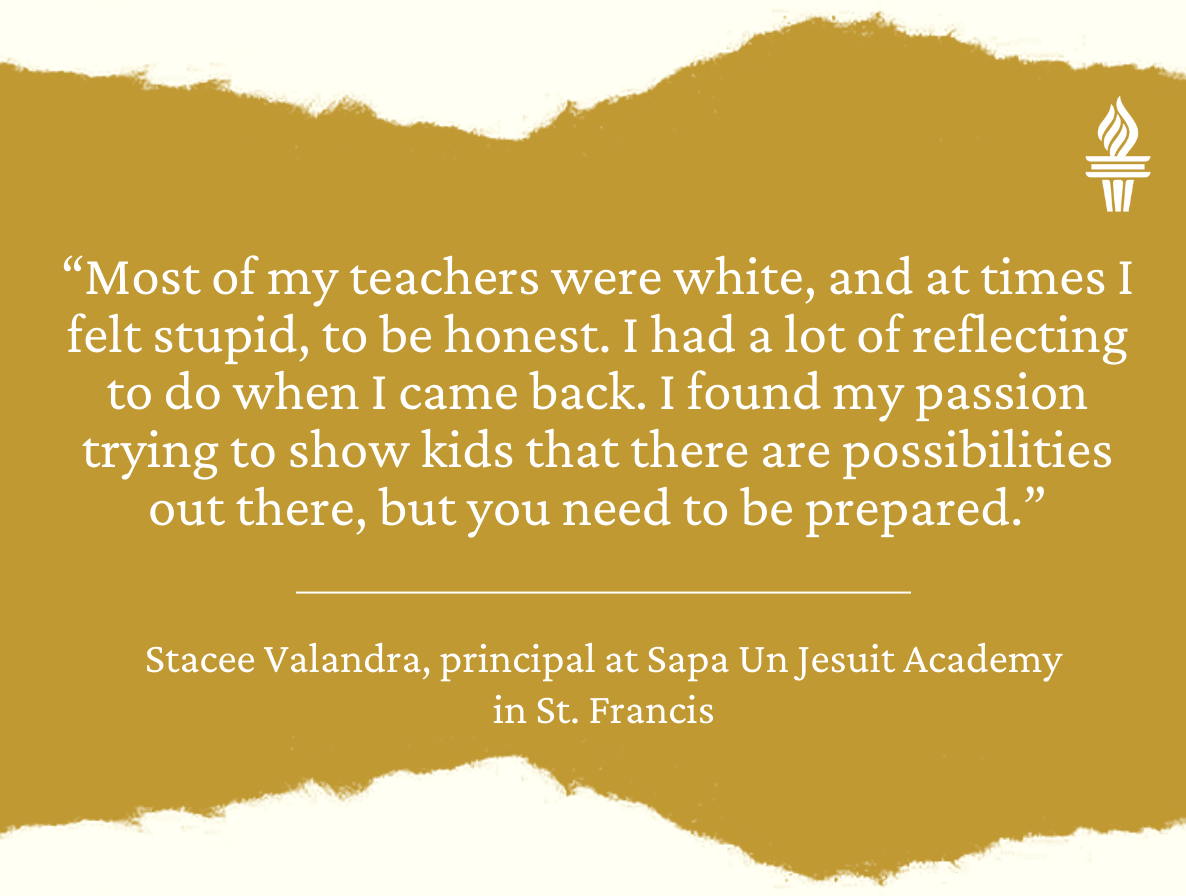

Valandra was a good athlete who attended public school in Mission and went to college in Nebraska to play volleyball. But she struggled in the new environment and moved back home.

“I didn’t make it – I’m one of those statistics,” said Valandra, now principal at Sapa Un Jesuit Academy in St. Francis. “Most of my teachers were white, and at times I felt stupid, to be honest. I had a lot of reflecting to do when I came back. I found my passion trying to show kids that there are possibilities out there, but you need to be prepared.”

It’s a daunting task on this reservation in south-central South Dakota, where high birth rates and low household incomes make educational structure a major priority for tribal officials, with limited success so far.

The Todd County School District, a public system with 97% Native American enrollment, had proficiency scores of 12% in English and 9% in science on the latest South Dakota Department of Education report card, with an attendance rate of 32%. The state averages were 50% in English, 43% in science and 86% for attendance.

U.S. Census data show that 15% of Todd County residents aged 25-plus have a college bachelor’s degree or higher, half the statewide average. Lacking educational standard-setters at home makes it tougher to inspire young people in the classroom, said Cindy Young, education director of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe.

“We provide services to help the parents however we can,” said Young, who has also worked in education on the Pine Ridge Reservation and at St. Francis Indian School. “A lot of the time those parents aren’t educated themselves and they live way out in rural areas, so it’s harder to get those kids to school.”

Low tuition, more family commitment

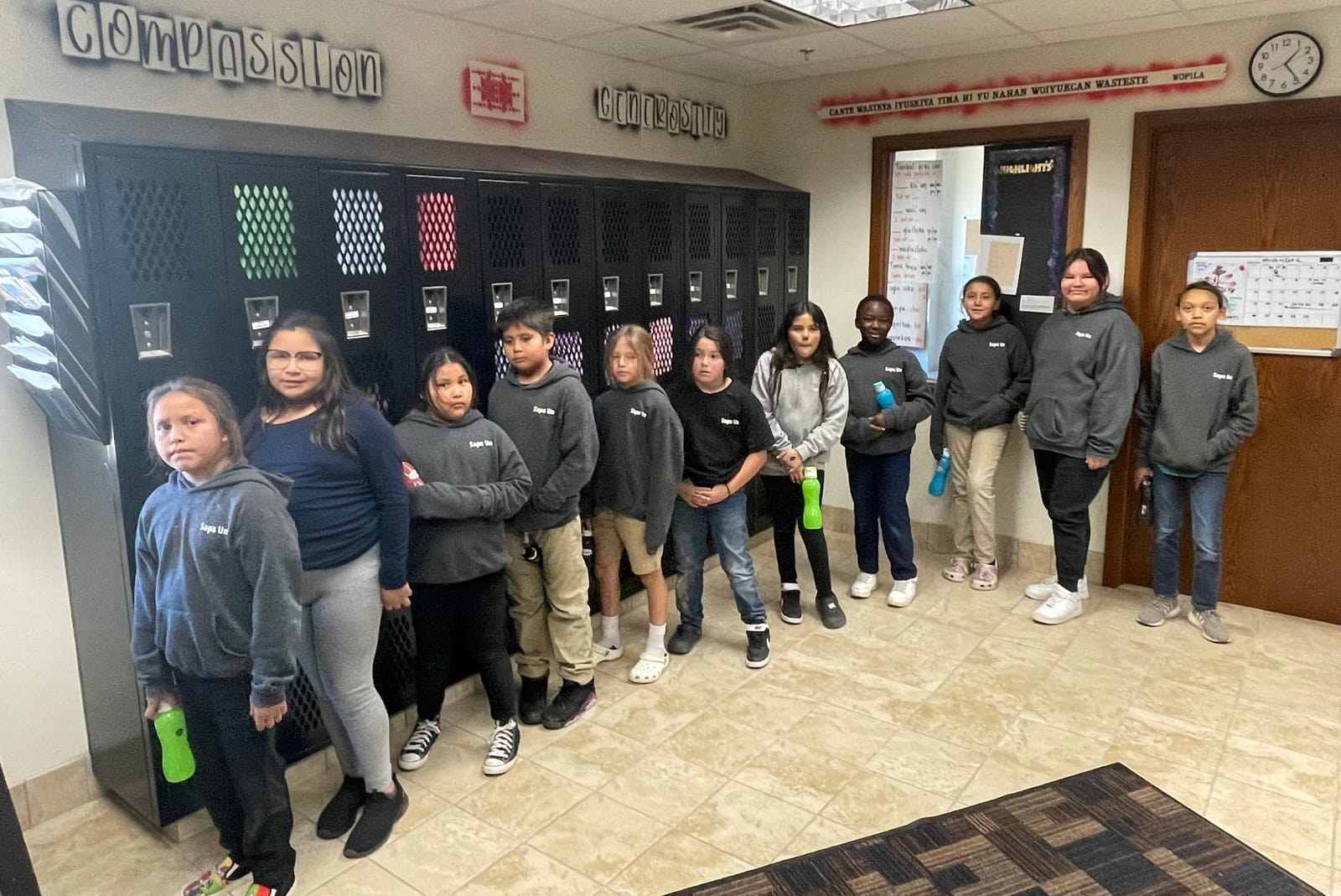

When Valandra arrived at Sapa Un Academy in 2014, there were only about 15 students and very little formal structure. But the concept of including Lakota culture in the curriculum and engaging parents in the process was paramount.

The K-8 school now has about 45 students, with the goal of preparing them to succeed in high school by emphasizing their strengths and interests. There are five teachers and one aide, with several of the grade levels combined.

“It’s very student-based, with small class sizes, which allows us to move kids around in spaces based on need,” said Valandra, who started as a kindergarten teacher and kept amassing more responsibility. “But what really makes us special is that we strive every day to focus on Lakota values such as compassion, generosity, respect and humility.”

A recent focus on compassion included hands-on experiences such as shoveling sidewalks for elders, reading to nursing home residents and organizing a blanket drive “to help keep our residents warm,” said Valandra, who enlists parents to help with the outreach.

The school was founded by the St. Francis Mission as part of the Jesuit nativity model of schools, which includes free or low-cost tuition, longer school days, an extended school year and opportunities for summer camp.

Lakota values are part of lesson

St. Francis Mission president Rodney Bordeaux, a former head of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said it was important to give reservation families a choice beyond St. Francis Indian School – which is funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs – and public-school districts such as Todd County, Winner and White River.

“There was a need for a school setting focused on academic achievement, leadership development and culture,” said Bordeaux, a graduate of Augustana University in Sioux Falls. “Parents are a big part of that.”

The Jesuit model has found success on the Pine Ridge Reservation with Red Cloud Indian School, part of a tradition of Catholic and Jesuit organizations providing educational opportunities in reservation communities.

Rather than de-emphasizing Native culture and traditions in favor of religious instruction, Bordeaux said the Jesuit nativity model celebrates Lakota heritage and language while still working to prepare students to succeed in a “white dominant” culture.

“It stems back to when we were put on reservations and our chiefs asked the ‘black robes’ to come and educate our people,” Bordeaux said. “They knew back then that we had to get educated to compete in the white man's world, and it’s still the same today. If you're not academically prepared, you cannot compete in this world.”

Sapa Un is funded almost entirely by private donations. Annual tuition is $100. Valandra said the St. Francis Mission would like to expand the school facility and offer K-12 instruction in the future, but she’s proud of the progress seen over the first decade.

“It’s a different kind of commitment because we don’t have busing,” Valandra said. “So parents are responsible for bringing their kids and picking them up every day and being involved in certain functions. We do have that conversation with families. You know, like, ‘This is our expectation of how you will participate here.’”

Todd County's profile: Younger, poorer

The reality of life on Rosebud makes it difficult for many households to fulfill those obligations.

Todd County has a median household income of $33,792, less than half the state average of $69,457, according to U.S. Census data.

Residents under the age of 18 account for 41% of the population in Todd County, compared to the state average of 24%.

Even with federal and tribal assistance, those factors put stress on households with children, making it challenging for parents and students to be actively engaged in the educational process.

“People always argue for academic attainment as an important vehicle to achieve upward mobility,” said demographer and South Dakota State University professor Weiwei Zhang, who studies population and economic trends in the state. “But when you’re in a group facing persistent poverty, you could have numerous financial burdens that hinder your path to a good education. So poverty becomes the reason rather than the result, and the cycle continues.”

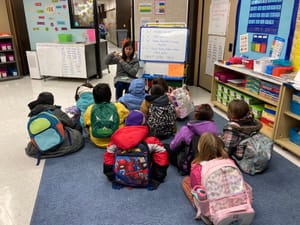

The Sicangu Lakota Oyate Head Start program has centers in Mission, Rosebud, St. Francis, Parmelee and other locations, providing early education opportunities for pre-kindergarteners.

Vonda Pourier-Whipple, the program’s director, noted in her annual report that under-enrollment and staff shortages have been major concerns since the COVID-19 pandemic. Problems existed before, she said, “but nothing compares to the magnitude of the past two years.”

Starting a cycle of opportunity

The Rosebud Tribe Education Department provides early intervention through its Lakota Tiwahe Center for parents of infants and toddlers with developmental delays or disabilities. Services include screening and evaluation, parent training and placement programs in public school districts if special education is needed.

“If kids are not getting the services they need, we make home visits to try to encourage the parents to get them services,” said Young, the tribal education director. “If they’re negligent, then we have to take further action with the Department of Social Services or our courts to make sure those kids are getting what they need.”

The tribal education department also started a “Building Bridges” program to emphasize the need for parent advocacy and involvement to improve the academic environment on the reservation.

Much of that is generational, with parents who graduated high school or college passing that knowledge and expectation down to their children. Growing pains are part of the transition.

Valandra, whose own college experience fizzled before she regained her footing and earned her teaching degree, is proud to see her daughter, Caelyn, attending the University of South Dakota in Vermillion as a track athlete and kinesiology major, hoping to pursue a career in physical therapy.

Success stories are the ones we should be highlighting, she said. The best way to do that is to make more of them.