Part 3 of a 3-part series.

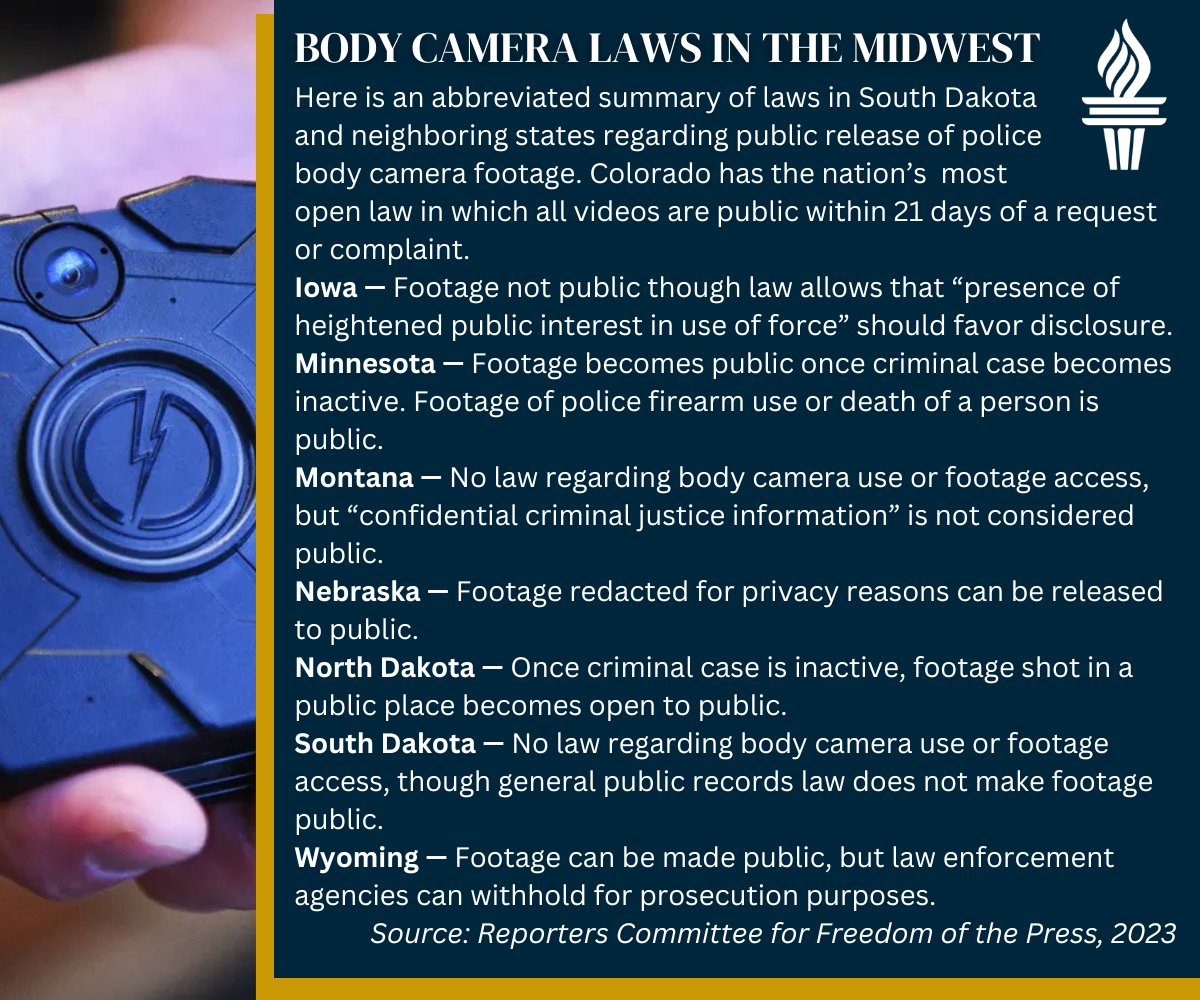

In 2020, a bill was filed in South Dakota that would have spelled out extensive rules for how police body camera footage can be obtained, maintained, used and shared.

Then-Sen. Reynold Nesiba, a Sioux Falls Democrat and primary sponsor of the bill, said that without a state law, police agencies across the state are on their own to decide how and when to use cameras, what happens to the footage and who should have access to the videos.

Without such a law, South Dakota would remain behind many other states that already regulate police videos, he said.

"In South Dakota, we have a patchwork and it depends on the individual police department … (and) I think it puts our law enforcement in a really difficult position,” said Nesiba. “I think it would be helpful to have guiding statute under what conditions it becomes a public record, who can ask for that record and under what conditions it can be released or held back."

Opposition to the measure came from state, county and local law enforcement officials, who testified that the measure was unnecessary because police agencies across the state use a set of "best practices" to guide use of body cameras.

The six-page bill, Senate Bill 100, never made it to a vote. Instead, the measure's original language was gutted immediately in committee and an amendment to recommend a legislative summer study session on body cameras videos was voted down.

New records laws unlikely in South Dakota

Since then, no other police video bill has been filed in the Legislature, according to a review of measures filed.

Given the current makeup of the South Dakota Legislature, support for enacting legislation related to release of police videos appears unlikely, said David Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota NewsMedia Association.

"We are on an island because our law is so weak in this area. And a consequence is loss of public trust and having full confidence in the accountability of law enforcement," he said. "That's not to say that distrust is the default because it’s not. But by not having good public access to these types of records, it can feed distrust and misinformation in the community."

Bordewyk pointed out that it took him and other First Amendment advocates several years to make it legal for police agencies in South Dakota to release criminal booking photos and police logs that show when and where officers respond.

"Those are commonplace public records in every other state in the nation forever, and it took moving heaven and earth to make those a public record in South Dakota," he said. "There’s this embedded DNA that because we’re a small state, we know each other and trust each other, and we can trust law enforcement is going to do the right thing."

"By not having good public access to these types of records, it can feed distrust and misinformation in the community."

-- David Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota NewsMedia Association

State Sen. Helene Duhamel, a Rapid City Republican, told News Watch in an email that she supports the current open records law, which gives law enforcement agencies full discretion on if or when to release police videos to the public.

"I am not pursuing changes to current public records laws involving law enforcement video," wrote Duhamel, a former television newscaster who now works as the spokeswoman for the Pennington County Sheriff's Office. "Body worn cameras are used every day by our largest agencies in South Dakota. It is one of the most successful policing reforms of the 21st century."

Duhamel said police videos can be seen by the public if they attend court proceedings where the videos are shown. "The video is evidence and not entertainment," she wrote.

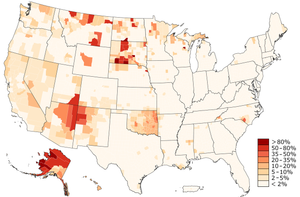

South Dakota ranks low in openness

South Dakota ranks at or near the bottom in more than a dozen analyses of public access to records, especially when it comes to law enforcement agencies, said David Cullier, director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida.

“They allow police to keep everything secret, and that’s against the basics of public records laws that have been around for hundreds of years,” he said. “If I lived in South Dakota, I would be up in arms because it turns out South Dakota is one of the most secretive states in the nation.”

Cullier said expanding public and press access to law enforcement records tends to make police agencies more transparent but also more accountable for their actions. And it ultimately leads to better performance by officers in the field, he said.

“It’s a way of making sure our police officers are doing their jobs that we entrust them to do because the body cams tell the story,” Cullier said. “When they deny records requests, they’re not saying ‘no’ to journalists and the media. They’re saying ‘no’ to the million people who live in South Dakota.”

Cullier said the American public has demanded more access to police videos after several high-profile incidents in which illegal and misreported shootings by police officers were captured on camera.

Among them: the 2014 killing of Laquan McDonald by a Chicago police officer; the 2015 South Carolina shooting death of Walter L. Scott, who was unarmed and running away from the officer who shot him; and the 2020 murder of George Floyd by an officer in Minneapolis.

In the McDonald killing, officer Jason Van Dyke initially reported that the 17-year-old had charged at him with a knife, and the shooting was ruled justified. A year later, when the video was released publicly, it showed the boy walking away from officers and not brandishing a knife prior to being shot 16 times. Van Dyke was convicted of second-degree murder.

Despite calls for more openness, and some state laws passed to expand open-records laws, most state legislatures have not taken steps to improve public access to police videos, Cullier said.

“I think we’ve seen a public push, especially since Floyd and other police brutality and killings,” he said. “Unfortunately, I don’t think a lot of legislatures have been moved by it. And I don’t think we’re going to see improvement unless the public continues to demand it.”

Challenging even for lawyers to obtain videos

The ability of prosecutors or judges to block access to videos can protect officers who might have acted illegally or improperly, said Jeffrey Montpetit, a Minneapolis attorney who has worked several civil cases involving law enforcement activities in South Dakota.

“I know of two cases I had in South Dakota where the courts basically said this video isn’t getting out because we don’t like what it shows,” he said.

The lack of access to police videos can inhibit the ability of the public to file civil claims against law enforcement officers who are alleged to have used excessive force or violated someone’s rights, Montpetit said.

“Without video, you’re out of luck,” he said.

“When they deny records requests, they’re not saying ‘no’ to journalists and the media. They’re saying ‘no’ to the million people who live in South Dakota.”

-- David Cullier, director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida

Defense attorneys who take cases on a contingency basis are unlikely to accept cases where a judgment might come down to the word of a police officer versus the claims of a member of the public, he said.

“The trooper, sheriff or police officer can write some B.S. report that the defendant resisted or took a swing at him,” Montpetit said. “Then all you’re getting is a credibility comparison between someone who may be a felon and a law enforcement officer, and you're going to lose those cases.”

Also, members of the public who cannot afford to hire an attorney are unlikely to obtain videos that could help make a case against an officer or the government, he said.

“Without video, there’s not a lot of options for lawyers to undertake those efforts,” Montpetit said.

Rural sheriff supports a possible state law

Alan Dale, sheriff of Corson County, said videos of interactions with the public or perpetrators have mainly been used to help prosecutors prove crimes or have helped his deputies respond to unwarranted complaints.

“In one incident, we had someone complain the officer searched a vehicle without cause. And when we watched the video, it showed the man actually giving the deputy his consent to search,” Dale said.

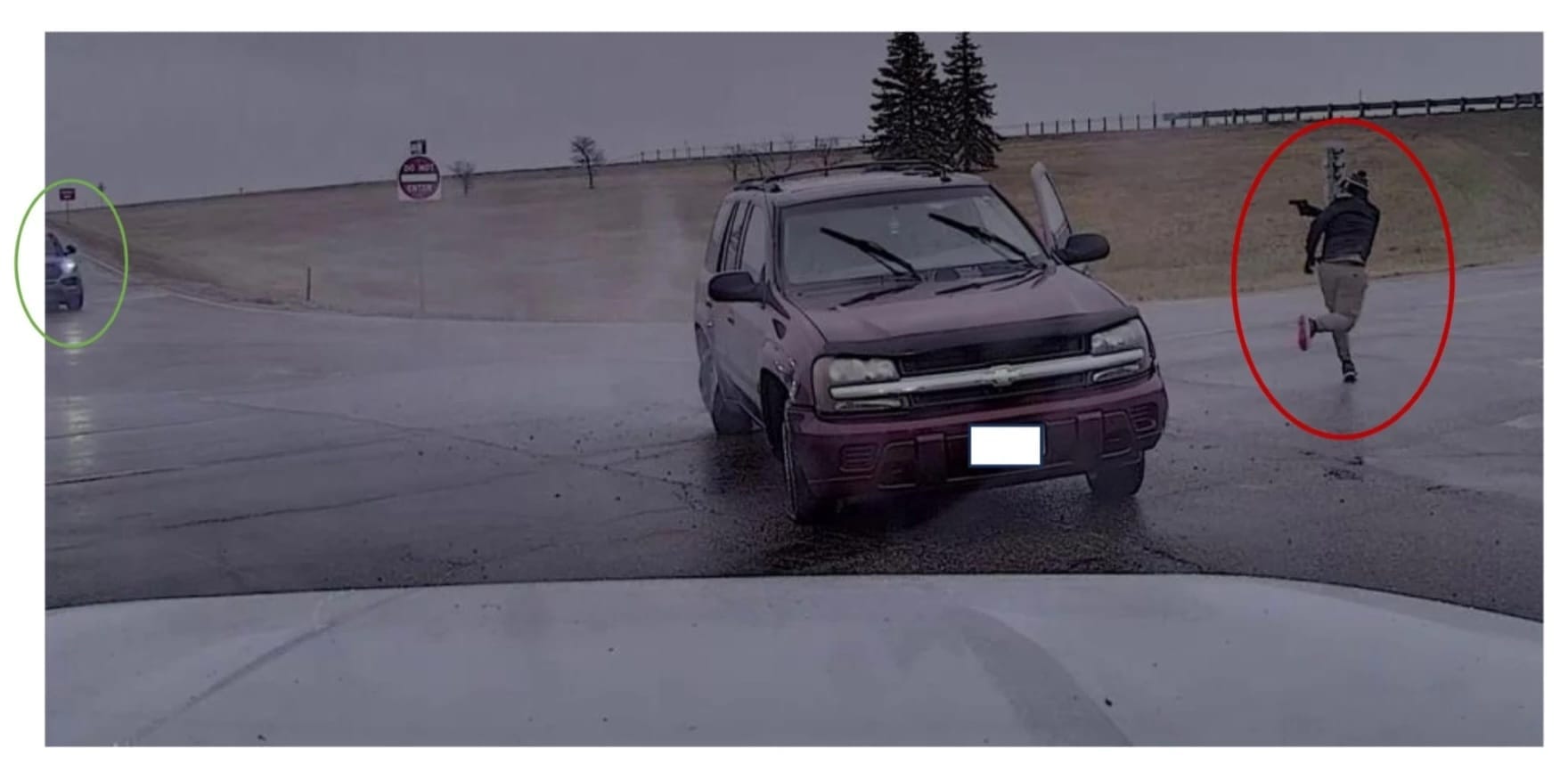

News Watch submitted a request to view videos of a June 30, 2023, incident in which a Corson County deputy and tribal officers engaged in a vehicle chase with 25-year-old Samir Albadhani, who brandished a gun before being shot and wounded by officers. Dale forwarded the request to the local state’s attorney, who declined the News Watch request.

Dale said he isn’t sure if police videos should become an open record for press or public viewing in South Dakota, but he would support some form of legislation to create a uniform approach for cameras and videos for all agencies across the state.

“When I first started in law enforcement, we didn’t have cameras,” Dale said. “But now I wouldn’t want to be in law enforcement without them because the cameras don’t lie.”

"I don't feel that we're done yet, and I feel there's more work to be done on that."

-- South Dakota Attorney General Marty Jackley

South Dakota Attorney General Marty Jackley said that while serving two separate stints in the office, he has formed three task forces to examine public meetings and records laws, which have led to more openness.

Jackley, who is running for South Dakota's lone seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, said he is willing to ask his ongoing open meetings task force or a new task force to consider whether police videos should be more publicly accessible.

"I don't feel that we're done yet, and I feel there's more work to be done on that," he said.

Read parts 1 and 2 of the 3-part series:

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact content director Bart Pfankuch at bart.pfankuch@sdnewswatch.org.